My research program focuses on decision making processes, specifically focusing on self-control, emotion regulation, and resource allocation (time, money, material goods). Prior and current research projects have investigated these processes across a range of contexts including (emotion regulation strategies, sustainability behaviors, dieting, charitable donations, Facebook usage, consumer decisions) with a range of methods (brain imaging [fMRI], experience sampling, computerized tasks, web scraping, experimental designs, qualitative coding).

Some projects are highlighted below.

Self-Control and Emotional Well-Being

We currently understand which emotion regulation strategies are successful and which are unsuccessful, but there are open questions regarding how these translate to everyday life’s dynamically shifting events and emotions. Using experience sampling methodologies we are exploring how individual’s regulation strategies influence their shifting affect over the course of days and months.

Simulation studies in our lab and others have also investigated the validity of different emotional markers in social media data. Word counting and simple computerized methods are quick and easy to implement but they may not capture shifts in affect in the same way that human coders are able to pick up on subtler cues. There are tradeoffs in the choice between faster computer methods and slower but more efficient human-based ones. Using simulations we have been able to compare the effectiveness of methods at different sample sizes and help evaluate external validity more effectively.

Consumption and Sustainability

While research in decision making tends to focus on making tradeoffs and choices between options, my research addresses the motivation to acquire and consume, including the emotional and attributional factors that are involved.

In my work with Dr. Stephanie Preston we draw on evidence from multiple disciplines to inform hypotheses and research questions. In uncertain environments animals hoard food more than in predictable environments (Preston & Vickers, 2014). Some of my early work investigated whether this mechanism has been conserved across species and leads to increased hoarding of objects in humans. With the generous funding of the Graham Sustainability Institute we have found multiple effects with specific emotions (e.g., anxiety) as well as appraisal dimensions within emotions (e.g., more or less uncertain types of sadness). Ongoing work is investigating whether populations with affective disorders (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder) show the same effects as subjects manipulated into short-term emotional states, how impulsivity influences the acquisition of primary compared to secondary reinforcers, and how ownership influences decisions to donate or discard objects (including the neural underpinnings of these decisions).

![]()

Moderation plot:

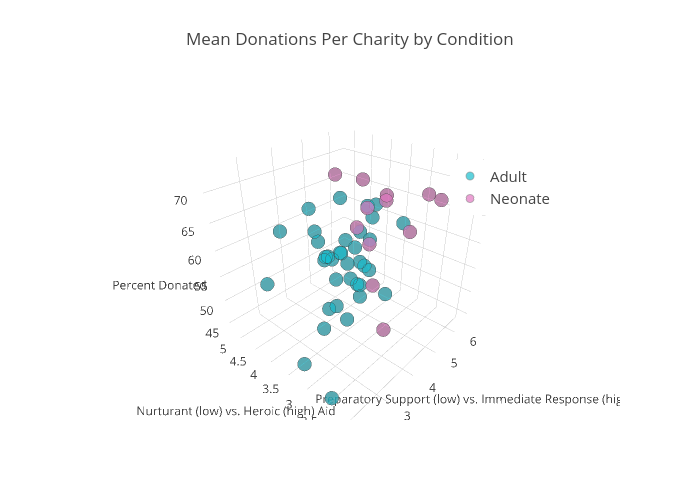

In a related vein, we have investigated the factors that drive people to donate to different charitable organizations. Charities will serve varied causes (e.g., war, homelessness), victims (e.g., kids, veterans), and both of these may be framed in different ways. We have begun exploring both how charities are framed influences the amount of money that people donate as well as the neural underpinnings of these behaviors.

The Construction of Value

The Construction of Value project focuses on how specific appraisal dimensions and our cognitive architecture work in sync to influence choices. For instance, when Hurricane Katrina devastated the city of New Orleans some onlookers expressed sympathy for victims while others blamed victims for living in dangerous flood zones. Many charitable solicitations rely on a popular belief that helping victims in need is the right course of action. However, appraisal theory suggests perceptions should be influenced by the appraisals activated in each individual, not the objective situation.

In work with Drs. J. Frank Yates and Stephanie Carpenter we are isolating the effects of single appraisal dimensions. For example, we have investigated how appraisals of control influence choices to help others. Situations can be thought of as caused by either human or situational causes (i.e., out of people’s control). These appraisals can be shifted in people and change helping behaviors depending on the target of the appraisal. For example, the manager of the homeless shelter appraised as being in control of the situation will be viewed much more favorably than a homeless person who is appraised as being in control of his negative situation. We are expanding this work into other domains and appraisal dimensions.

The Foundations of Emotional Complexity

Research on emotions and decision making has focused on differences between undifferentiated, valenced emotions (e.g., negative vs. positive) or differentiated, specific emotions (e.g., sadness vs. fear vs. anger). Real life rarely elicits such stark distinctions in our emotional experience. After the loss of a cherished loved one, such as a parent or spouse, you are more likely to feel a complex mix of sadness that they are gone, fear of what your life will be like without them, and anger at the doctors for not saving them, among other emotional responses (e.g., Horowitz, 1990). Few people would simply feel sad.

In research with Dr. Phoebe Ellsworth we are exploring how complex or mixed affective states influence people’s emotional experiences. We have found that emotional complexity is associated with higher levels of both emotional intensity and distress in negative affective states. Interestingly, these also vary greatly between people within the same objective situation due to the appraisals that individuals make. Currently we are working to relate emotional complexity to prior research and understand how and when mixed emotions influence behaviors akin to specific emotions.