Former IPCAA graduate student and now Dr. Katherine Larson successfully defended her dissertation earlier this month! Below is a brief abstract of her dissertation, which she has kindly provided. Further cause for celebration is that Kate already has a position lined up as a Curatorial Assistant at the Corning Museum of Glass in Corning, New York (a museum that lines up well with her interests, as you can read below). Congratulations Kate!!!

Dissertation Title: From Luxury Product to Mass Commodity: Glass Production and Consumption in the Hellenistic World

“My dissertation research began with the question of why glass vessels and small objects were so common in Mediterranean assemblages of the Roman period and later, but were quite rare in the first millennium BCE. Traditionally, this major change has been tied to the invention of glass blowing, which spread from the eastern Mediterranean to Italy and the west in the later part of the first century BCE (the earliest known blown glass comes from a deposit in Jerusalem dated to the second quarter of the first century BCE). But having worked on archaeological sites in Israel, I knew that glass was quite common in Syro-Palestine, Egypt, and some Aegean islands (like Delos and Rhodes), where grooved glass bowls, feather decorated beads, polychrome perfume vessels, and small gaming pieces are considered standard objects in Hellenistic assemblages. Anthropologists who study craft production and technology have been arguing against deterministic narratives of invention as the single driver of technological progress for some time now, and I was interested in complicating the traditional teleology of the so-called “blown glass revolution” as being solely responsible for the major change in glass production and consumption habits during the early Roman period.

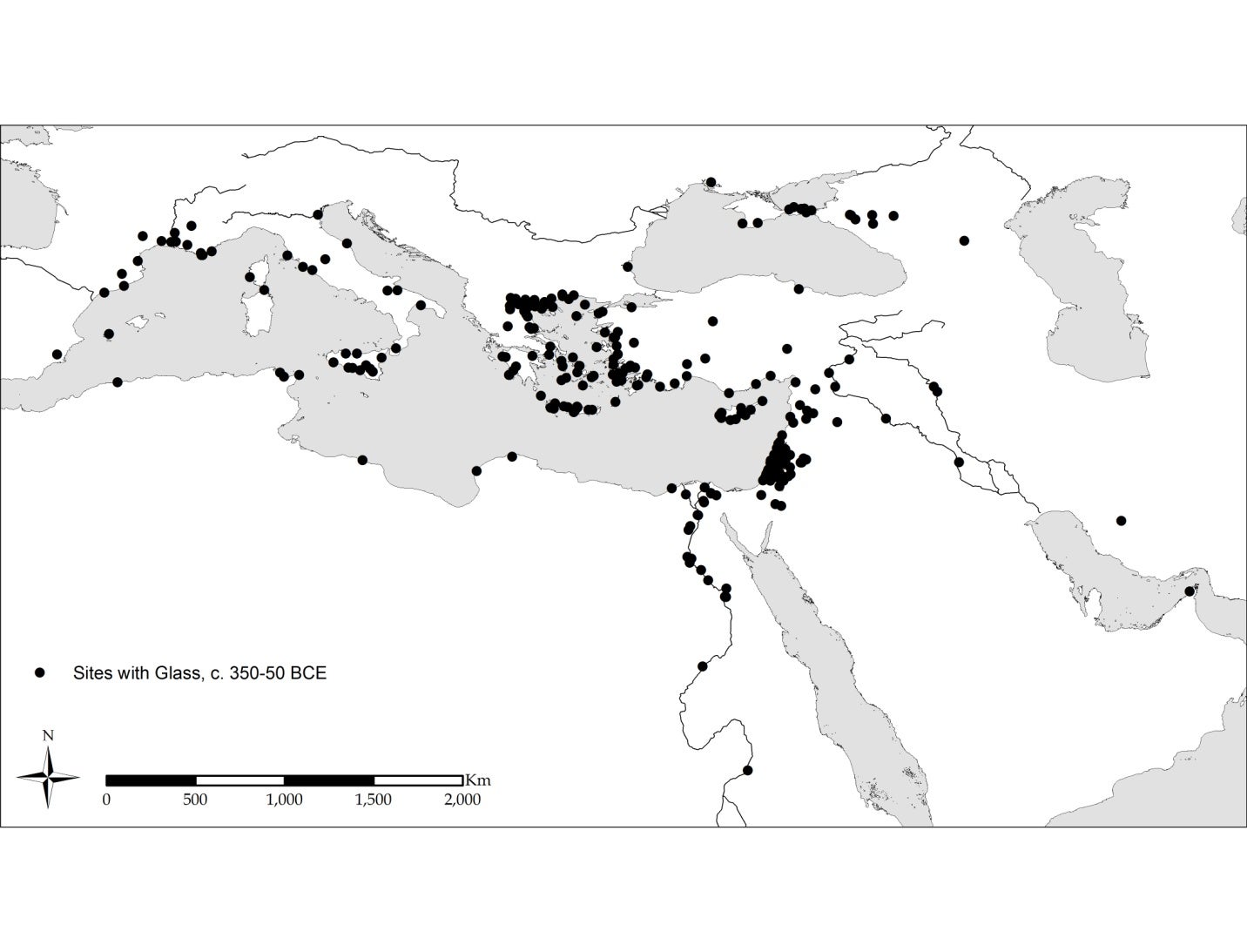

As I argue in my dissertation, the key change in ancient glass production and consumption habits was a conceptual, not technological, revolution. Beginning in the second century BCE, individuals began to drink from glass bowls, adorn themselves with glass beads and pendants, spin with glass spindle whorls, play games with glass astragaloi and gaming pieces, and decorate their furniture with glass inlays. While some of these objects and behaviors existed previously, they were deployed in larger quantities and in a wider variety of contexts and sites than ever before. No longer restricted to funerary, religious, and palatial arenas as they had been in the Classical Mediterranean and Achaemenid Near East, glass objects appeared in urban and rural houses, refuse deposits, and construction fills with increased regularity over the course of the second and first centuries BCE. By documenting published glass objects from archaeological contexts dated from c. 350-50 BCE in the Mediterranean, Black Sea, and Near East, I have demonstrated the overall rise in quantity of objects and a shift in their contexts of use and deposition over these three centuries. This change was localized in the eastern Mediterranean, and especially southern Syro-Palestine.

I conceptualize this change in glassware as a progression from luxury to mass production and consumption. Luxury glass objects continued to be produced and used throughout antiquity, but the adoption of glasswares into a quotidian, lesser elite sphere was a dramatic functional shift of the Hellenistic period which in turn allowed for the experimental innovation of glass blowing. Ambitious and moderately wealthy individuals engaged in elite identity practices centered on glasswares, including conspicuous consumption and elaborate drinking and dining. Producers responded to growing consumer demand by exploiting natural resources to manufacture raw glass, simplifying manufacturing processes, and opening new workshops, which trained more workers and reached additional markets. In turn, such experimental and entrepreneurial workshop behavior eventually facilitated the technological innovation of glass blowing. But the concept of glass as a mass commodity sparked the invention and application of blown glass technology, not the other way around.”

Sites with Hellenistic period glass objects. Image credit: Katherine Larson. _________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________

Have updates of your own to share? Submit them to ipcaanewsletter@umich.edu