The Electric Gate

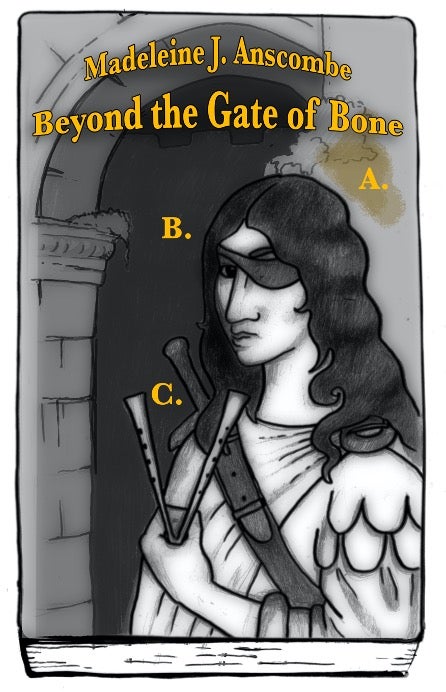

This is the cover of Ada’s copy of Beyond the Gate of Bone by Madeleine J. Anscombe. The important details:

-

A stain born during a very boring dinner party. Ada always reads under the table even though her mother has told her not to be rude and could you please try to respond with more than monosyllables when people ask you questions, Ada? Be good and say, “I’m well, how are you?” when someone asks how you are. Don’t just say, “Fine.”

-

This is Mad Janet. Ada dresses up as Janet for Halloween, but all the kids at school mistake her for a pirate because of Janet’s eyepatch; she tries to explain three times before giving up and accepting her fate as a pirate.

-

Mad Janet’s most precious possessions: her ivory aulos (which she uses to play music for ghosts), and her sword, Sunbeam (whose hilt is just visible over one shoulder). Ada asks for a sword for her fourteenth birthday, and her parents say no; she asks for an aulos—or a flute at least, since none of the adults know what an aulos is—and they say yes, but then she has a flute, and she doesn’t know how to play it. Her mother suggests lessons, and Ada almost agrees, until she realizes that her mother is really just tricking her into doing more school-type things.

#

Beyond the Gate of Bone by Madeleine J. Anscombe proceeds as follows, more or less:

Act 1: Janet is the second daughter of the Lord of the Shining Islands. She runs away from an arranged marriage to join the minstrel Tristram and his troupe.

Act 2: Janet discovers that Tristram is in fact an infamous bard known for chasing his deceased lover past the Gate of Bone into the Underworld (only to lose her to the King of Death and Dreams). Ever since, Tristram makes more or less regular trips between the realms of life and death. He leads his troupe beyond the Gate of Bone; they stop at the court of Count Malacoda, whose land is threatened by a wicked Fiend.

Act 3: After various other combatants prove useless against the Fiend, Janet sets out in secret for its caverns and faces many perils along the way. The Fiend distorts her path and torments Janet with her own fears. But then Janet sings the forgotten songs she has learned as a member of Tristram’s troupe. The Fiend dances with Janet, and while it is distracted by its own merriment, she beheads it with Sunbeam—but the Fiend’s shadow still manages to devour one of her eyes. Her absent eye sees into death and sleep ever after, and she is, henceforth, known as “Mad” Janet.

#

The only person at school who gets it is Maggie. Unfortunately, Maggie is also a senior and about to leave Ada all alone in this “disreputable husk of a hellhole” (i.e. high school, as Maggie calls it, in a very Anscombean turn of phrase).

“I wish it actually was a hellhole,” Ada says.

Maggie, as always, understands. “That’d make it more interesting, right?”

Maggie smells like cigarettes, her hair is Kool-Aid red, and she is somehow also a straight-A student. Ada and Maggie know each other from Latin class. Sometimes other people mistake Ada for cool when they see the two of them together. Ada will miss that.

Most of all, Ada will miss drinking red bull with Maggie during late night study sessions at Maggie’s mom’s place, and she will miss getting into arguments about whether or not Mad Janet and Tristram should be a couple (Ada thinks so, while Maggie thinks Mad Janet has a thing for the Fiend).

#

Beyond the Gate of Bone by Madeleine J. Anscombe is full of skeletal instruments: harps and lyres with frameworks assembled from satyrs’ ribcages, panpipes made of hollowed-out finger bones, and hunting horns cut from chimeras’ heads. There are also lots of ancient codices with pages of carved ivory full of very old songs that can reshape life and death and dreams. Everything in Madeleine J. Anscombe’s world is made of pieces of dead myth, horn and bone, given new life. The eponymous Gate of Bone is engraved with ancient words and music.

As she reads, Ada holds her book up and imagines that the spread facing her—the two white pages—are likewise doors, a gateway of a sort. They are talkative doors, and she likes listening to them better than she likes listening to most people.

The obvious occurs to her: every book is a gate. Some books are just like the Gate of Bone, leavings of the dead, yet full of their voices. (Anscombe, for instance, is very dead, yet very loud in Ada’s experience.)

Reading can be like entering into a dialogue with beloved ghosts.

#

Ada is the weird quiet girl. Or, sometimes, the “creepy” quiet girl. “Weird” Ada can deal with. “Creepy” is where things get uncomfortable, where balled-up bits of paper and rubber bands wind up in her hair.

On the school bus, she curls into herself like a harassed pill bug: knees pressed against the seat in front of her, shoulders hunched forward, nose close as it can get to the pages in her lap without her vision going fuzzy.

Maggie has left the hellhole, but she still sends Ada messages. She tells her about a website: Gate of Bone Online (or, to its denizens, GoBO).

This is around when Ada starts spending way too much time on the internet (a new and mysterious landscape). At first glance, GoBO doesn’t really match Anscombe’s book with its gothic castles and ruins riddled with ivy. GoBO consists of a glowing grid of green-and-gray, boxed lines of text and numbers—a strange collective poem dreamed up by innumerable bored and lonely teenagers:

Ada adopts a new identity: she becomes a piper. She clicks on a line in the poem and a whole new story unfolds for her, and she is ecstatic to realize that she can be a part of things, she doesn’t have to stay on the other side of the gate and press her ear hopefully against it, listening for faraway songs.

She can be loud for once and join the tune.

Nobody mistakes her for a pirate this time.

#

Madeleine J. Anscombe (or, sometimes, MJA), author of Beyond the Gate of Bone, has been dead ten years, six months, and twelve days by the time Ada finds GoBO. Anscombe’s death means an easy rebirth. She wrote about ghosts after all; why shouldn’t she become one? GoBO represents an elaborate kind of séance. The site’s participants will learn about things like the Death of the Author when they go off to college, but for the time being, they’re happy to be haunted by Anscombe; they have no interest in letting her die properly.

Ada and company go hunting through the caverns of the Bolgias for moon-lizards (salamanders with glowing mother-of-pearl skin) and eat yew berries in the winter gardens of Cocytus. Their voices join the chorus of trees in the singing forests where the wind whistles broken lullabies through hollow branches and twigs. And all the while, Anscombe’s prose bleeds into theirs. That is to say, she possesses them (kind of). GoBO’s children have a vocabulary that doesn’t really belong to teenagers, full of words like troglodytic, eburnean, lachrymose. They know way more about skeletal anatomy than they should, given their familiarity with characters and places named Metacarpus, Calcaneus, Maxilla.

And because they’re teenagers, there are also relationships that blossom and fade—this is the first time that Ada ever manages to flirt with anyone (the “anyone” in question: a dryad in the winter garden). She tries to ignore her parents’ concern about the many hours she’s wasting with something that isn’t real, with people she doesn’t really know. She performs sighs at their many many warnings that the kids she’s interacting with might very well not be kids at all. “Don’t tell anyone your real name, Ada,” they say, and she yes-yeses, though she doesn’t get why it would be so bad to divulge something as trivial as a name. She’s shared thoughts and secrets that feel much more meaningful with her friends on GoBO. “And no personal information, no addresses or phone numbers…”

Ada wishes her parents would believe her when she says that she has no desire to meet anyone from GoBO offline, though that’s only a half-truth. Really, she craves something impossible: for GoBO’s spirits—not the solid and fleshy people who made them—to join her in the real world.

But it turns out that inviting shades to play on the wrong side of the Gate requires Ada to reveal herself to them—against her parents’ wishes.

#

There have been mutterings recently about threats against GoBO’s existence. There are copyright issues or something like that (according to rumor, Anscombe’s son has been laying waste to fans’ various homages to his mother’s work). GoBO’s admin—a young woman who plays a few different characters, including Mad Janet herself—has concocted a plan, a way to save GoBO, or at least a memory of it. She is a complicated kind of queen: half hero, half author, and wants to compile a hard copy of all her followers’ adventures. A new book. The conclusion that Anscombe, who planned a sequel, never got to write.

Mad Janet asks for everyone’s addresses, to send them hard copies of the final book they’ve all authored together.

Ada is terrified of losing GoBO, and she needs this book more than anything. More than she’s ever wanted a sword or a flute or anything like that. The circuit feels right: to pass beyond the gateway of Anscombe’s pages into the immaterial world of GoBO, then for GoBO to resurface in her own world as a solid thing of paper, with pages she can turn and know she helped speak into being. Then maybe the real Ada will become a little more like the brave and soulful piper who plays and laughs and drinks yew berry wine in the Underworld. Then maybe she’ll figure out how to care less when people call her creepy.

But Ada is not supposed to give away personal information.

When a manila envelope with Ada’s name on it magically appears, Ada’s parents scream at Ada and take away her TV and computer privileges for two weeks.

Can she have the book, at least? The ghost of a final book that was never written?

No, they say.

And so, the book disappears. Ada asks after its fate, and her mother will not divulge any details.

She imagines the book smoldering in the pitch pits of the Bolgias.

#

During her banishment from GoBO, Ada is stunned to recognize the Gate of Bone while plodding through The Aeneid in her AP Latin class.

It’s the sixth book. After consulting with the Sibyl of Cumae, Aeneas ventures down into the underworld to talk to his dead father, then reemerges, passing through the gate of ivory.

The gates of horn and ivory are passageways into and out of the underworld. The one material is translucent, the other opaque. Opaque ivory allows false dreams to pass, while translucent horn only lets true things through. Or something like that. (Doesn’t it sound like horn is the indiscriminate material, an avenue for both truth and falsity? Maybe the real issue is that ivory is bone and teeth, speaking material that is all too familiar, a part of us. Horn is foreign, the leavings of goats and bulls who cannot lie like we do.)

Whether the image makes sense or not—maybe because it doesn’t—reading the sixth book of The Aeneid drives Ada away from Anscombe at last, as she recognizes her world for what it is: nothing special or new at all. Just very old bones, repurposed.

As winter comes and erases the leaves from the trees, Ada ignores the windy music among the bone-white branches. She waits for the school bus. She watches a pigeon nod through the streets as it tries to shake a chunk of ice from its head, and she does not think of winter gardens.

In the spring, Ada leaves her parents’ home in the city and goes to college. She does a lot of Media Studies and Studio Art. She tries to take a dance class but is pretty bad; her teacher tells her that being bad is a legitimate form of artistic expression unto itself (and Ada almost believes that). Ada makes friends with people who understand her, who feel like a new family. Rubber bands stop finding their way into her hair.

#

When her parents decide to move, Ada takes the train home one weekend to help them pack and heft boxes.

She is rifling through dusty cabinets in the basement when she finds a manila envelope with her name written on it in apple-green gel pen. What’s this, she wonders.

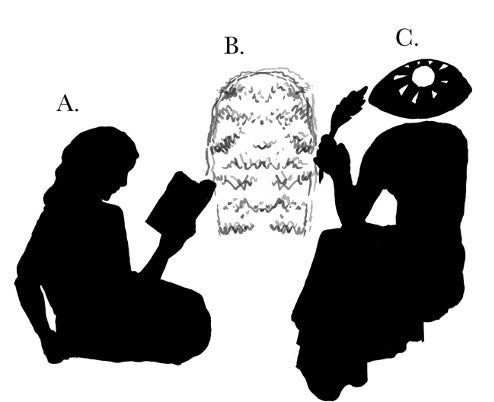

Ada opens up the envelope, perplexed, and a fat packet of papers slips out:

It’s a little hard to decipher, but Ada thinks that these are the things represented on the cover page of the Chronicles of GoBO by Madeleine J. Anscombe’s successors: a crudely drawn flute, Mad Janet’s eye full of shadows, and the shadowy creature might be the Fiend, maybe?

Ada sits down on a cardboard box and flips through the manuscript.

Once, between high school and college, she tried to look for GoBO again, but found that the site had vanished (the threats from Anscombe’s son must have been real after all). Ada’s reading habits changed; she burrowed into grown-up stories (mostly nineteenth century British novels). Her memories of GoBO grew very blurry and distant—which felt right, in a way, for a world inspired by dreams of ghosts.

But here it is: a physical memento proving that world’s one-time existence.

And wow, it’s pretty bad.

There is an arc to Beyond the Gate of Bone. A derivative arc, maybe (since its core narratives and their dressings are all harvested from the detritus of old myths), but there it is: three acts, growth, change. Janet starts off as a spoiled and entitled young noblewoman and emerges as a hardened minstrel and warrior with an eye full of death’s shadows and an ear for enchanted song.

GoBO was not a place of change. Nobody ever had the nerve to cut a narrative thread off and call it done. For people obsessed with dying, they were all pretty allergic to ending their stories.

Ada wants to tear the whole thing apart, but then she remembers that there are more copies among GoBO’s exiles. The thought of her adolescent voice haunting strangers’ bookshelves makes Ada want to tuck herself away into the cardboard box she’s sitting on.

And then she recognizes Maggie in the manuscript. They’ve fallen out of touch, but Ada’s remembered Maggie is still the hero of their own personal hell with her cigarettes and perfect Latin. Maggie in the manuscript drifts in and out of chatspeak and writes a lot of run-ons overstuffed with adverbs—which Ada tries (feverishly, fruitlessly) to memorize.

By the end of the manuscript, Ada’s old character and her friends are still the same people with the same thoughts and feelings and problems. And what’s more, that not-change, it’s not just stuck in the manuscript. It’s in Ada, too. It’s always lain curled up in her brain or her gut or somewhere between those two regions. She recognizes weird words she still uses. An Anscombean language. After all this time (not so much time, really, but she doesn’t see it that way yet), MJA still manages to possess her.

And here Ada thought she had grown up or something.

#

Ada has developed an interest in puppet theater. Shadow puppets, to be specific. She cuts up paper and plastic to make her own gobos: stencils to obscure a light source so that it’ll cast a shadow onto a stage or a wall.

She thinks about ivory and horn, gateways opaque and translucent.

For her capstone project, she creates a play made of shadows. She calls it The Electric Gate.

Ada’s favorite gobo looks a little weird, kind of like an inverted eye. It’s a dark almond with an empty circle of pupil at the center for light to pass through. It’s supposed to be an eye full of shadows that can see into death and dreams. Ada realizes that all of this—the book, GoBO, and whatever the hell she’s doing now—has been a prolonged exercise in looking at the world through Mad Janet’s eye. Her sight is a keyhole through the Gate.

And then the walls are full of shadow puppets:

-

A girl finds a book, opens it up, and things change around her.

-

A crackling gate appears, full of static. The girl passes beyond the gate.

-

She meets a ghost with an eye where her head should be.

The ghost and the girl speak to one another, tripping through their own language, made of weird and pretty words strung together into nonsense sentences:

Instead of saying, I am well, how are you? They say, Crepuscular lamella, nacre?

The woman and the girl speak, their two strands of speaking entwine, become song. The shadows move and sway across the pale wall. There should be a real ending to the story at this point, some sense of growth and change, Ada realizes.

But instead, she would rather be like Mad Janet and join her shadows in a very old dance that doesn’t know how to end.

M.E. Bronstein is a PhD student in Comparative Literature who writes various kinds of dark fantasy and weird fiction when she should be working on her dissertation. She is a graduate of the Odyssey Writing Workshop and Clarion UCSD. You can find her at mebronstein.com.