“She almost died in a devastating car accident that took five lives; because of that, all her work possesses an existential edge. She is keenly sensitive to her own and her subjects’ human pain and finitude. She knows firsthand how anthropology can “break your heart,” because she is willing to allow it to come into her heart. When it does, it unearths her own buried memories of disappointment and suffering… she is a better anthropologist and scholar because of her vulnerability.”

-Robert Nash, University of Vermont, author of Liberating Scholarly Writing

Born in Cuba and growing up speaking Spanish in New York City, the need to understand the fluidity of identity in the Spanish-speaking world has inspired my journeys as a cultural anthropologist.

I began my career in Spain, studying family, property, and community in Santa María del Monte, a small peasant community in the province of León, at the base of the Cantabrian foothills. In Spain, where even tiny villages have richly documented histories, I moved between the field and the archive to develop an analysis of the way people thought about their traditions. My first book, The Presence of the Past in a Spanish Village, wove together narratives culled from historical documents with stories and legends told to me by village people. I have since returned to Spain many times, staying in touch with many of the villagers I met thirty years ago and their families, who are very proud of their heritage. I have also forged new bonds with the growing local group of ethnographers affiliated with the Museo de Etnografía in León, which made possible the Spanish edition of my book.

The village now has a wonderful website. Here is an interview with me for the Diario de León that was posted on the website.

I had the privilege to work next in Mexico. I was drawn to archival work then and initially concentrated my efforts on studying women’s witchcraft confessions in colonial times. But I was led back to the present when I met Esperanza Hernández, a woman who was rumored to be a witch in the small town in San Luis Potosí where I was living. The story of our friendship led me to write Translated Woman: Crossing the Border with Esperanza’s Story. There I reflected on the legacy of Pancho Villa and Mexican revolutionary history through the feminist cosmology of a street peddler who calls upon Villa’s spirit for valor in her struggle to be an autonomous woman. I drew on the Chicano critique of anthropology and on Chicana creative writing for my theoretical framework and wove in Gloria Anzaldúa’s ideas about borderlands and Alicia Gaspar de Alba’s concept of the literary wetback with new theories of feminist ethnographic writing. Writing in English about experiences lived in Spanish, I turned to the writer Sandra Cisneros to learn how to tell Mexican stories in translation, linking academic and artistic literary practices. It was thrilling to later adapt Translated Woman for the stage with PREGONES Theater, a Puerto Rican group based in the Bronx, which showed me what amazing possibilities exist for anthro-performances that build on inter-Latino coalitions and border crossings.

I kept in close touch with Esperanza through the years and was fortunately able to see her a few months before her death in 2014. Here is my farewell letter to her.

I began to travel to Cuba regularly in 1991 (having first returned to the island as a student in 1979) and felt it was urgently necessary to build a community of tolerance that would unite the island and the diaspora in a common quest for memory and meaning. I found myself doing ethnographic work of a different sort than I’d done before, engaging in dialogue with my contemporaries. I moved into an exciting interdisciplinary arena, becoming the editor of Bridges to Cuba, which brings together historical essays, testimonial writing, cultural critique, poetry, fiction, photography, and art. Bridges to Cuba became a pioneering forum for critical discussions about Cuban identity. I subsequently produced a follow-up volume, The Portable Island: Cubans At Home in the World, co-edited with Lucía Suárez, which considers the impact that immigration has had on the remaking of Cuban identity and ideas of belonging.

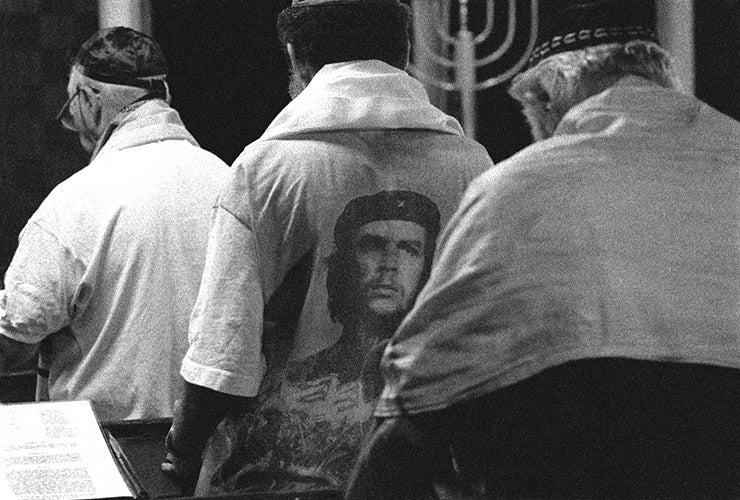

As I traveled back and forth to Cuba, I became aware of the globalized fascination with the island, which has generated a “Cuba boom,” allowing Cuban icons to circulate around the world, whether they are images of nostalgia found in the Buena Vista Social Club, or images of revolution encapsulated in the figure of Che Guevara.

I decided to focus my ethnographic work on the exoticized tiny community of Cuban Jews that remains on the island and how images of this “lost tribe” circulate in an international context that includes the United States, Canada, Latin America, Europe, and Israel. I began my research on Cuban Jews by making a documentary film, Adio Kerida/Goodbye Dear Love, which explored Cuban Sephardic identity on the island and in the diaspora. Highlighting themes of expulsion and departure that are at the crux of the Sephardic legacy, I interviewed a wide range of Cuban Sephardic Jews. Working with visual media allowed me to challenge stereotypical images of Jews and Cubans and to create a mosaic that included an Afro-Cuban boy of Jewish heritage preparing to emigrate to Israel, an elderly tango singer who dreamed of a Buenos Aires he had never seen, and my father, a son of Turkish Jewish immigrants to Cuba, who refuses to return to the island. Women Make Movies, the oldest non-profit company representing women filmmakers, distributes the film, which has been screened in film festivals in the United States, Canada, Latin America, Europe, and Australia.

After completing the film, I felt the need to offer a broader chronicle of the lives of Jews living in Cuba, and wrote a book, An Island Called Home: Returning to Jewish Cuba, addressing the preservation of memory by those of Jewish heritage as well as the important role played by converts, or Jews by choice, in the revitalization of Judaism. The book includes over a hundred black-and-white photographs by Havana-based photographer Humberto Mayol, who collaborated with me on the research.

Moving between English and Spanish, writing in both languages, I continue to be interested in researching the convergence of cultures and the identity of those who find themselves “in the between,” searching for meaning in diasporas.

I am currently working with photographer Randi Sidman-Moore on an upcoming book on the Cuban Jewish community in Miami. And I have a new project on “Dreams of Sefarad” exploring modern Sephardic identity from Istanbul to Havana to Miami and Seattle.

I spoke about this topic recently in the Stroum Lectures.

Some of the backstory behind this work.

About how one can be an anthropologist in one’s own community