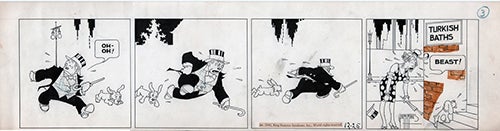

“Bringing Up Father (12/25/1940)”

“Bringing Up Father (12/25/1940)”

by George McManus (1884-1954) and Zeke Zekley (1915-2005)

23.25 x 5.75 in., ink on paper

Coppola Collection

The art on this comic strip is one of my favorites. The unique, art-nouveau style is just so crisp and clean – the intentionality of an artist laying down deliberate lines shines through.

On January 12, 1913, Bringing Up Father debuted, featuring an Irishman named Jiggs, who simply does not understand why his ascension to wealth (via the Irish Sweepstakes) means he cannot hang out with his friends, and his nagging, social-climbing wife, Maggie. The strip was an instant hit, possibly because of its combination of an appealing cast of characters with a unique look.

The strip deals with “lace-curtain Irish,” with Maggie as the middle-class Irish American desiring assimilation into mainstream society, in counterpoint to an older, more raffish “shanty Irish” sensibility represented by Jiggs. Her lofty goal—frustrated in nearly every strip—is to bring father “up” to upper class standards. By 1954, Jiggs’s Irishness had faded—the new generation saw him as just a rich guy that liked to hang out with a regular crowd.

Syndicated internationally by King Features Syndicate, Bringing Up Father achieved great success and was produced by McManus. In the early days, his brother Charles was an uncredited collaborator. Zeke Zekley was his assistant on the comic strip from 1935 to 1954. After moving from Detroit to LA, Zekley was unemployed after two weeks at Disney, due to the studio closing during the summer, and Charles noticed him sketching on a napkin at a diner and brought him to his brother’s attention. Zekley’s style was indistinguishable from McManus’s, and he took on more and more of the duties on the strip as time went on. A friend of Zekley’s, working on behalf of Zekley’s wife, has been regularly selling off the storehouse of originals that Zekley left behind upon his death.

This particular strip is from Christmas Day, 1940. The worries of the world do not appear in the funnies, but I still find it interesting to contextualize these comic strips in reminders of what was happening in the rest of the newspaper.

The second Christmas of the war was very different from the first for people in Britain. A year earlier, only Poland and Czechoslovakia had been occupied by the Nazis – and the ‘phoney war’ had yet to make much of an impact on peoples’ lives. The dramatic events of 1940 had seen the occupation of most of Europe – and the threat to Britain had become very real.

Britain was surviving the threat of invasion and was holding off the attacks. But British towns and cities were being laid waste on a daily basis. Thousands of families up and down the country were facing violent and sudden death. Tens of thousands of people were recovering from serious injuries.

George Beardmore wrote of a ‘dismal Christmas,’ in Civilians at War: Journals, 1938-46:

…in the absence of home, friends, and relations, with only a few cards and parcels sent to us. But we were in God’s own heaven compared with many, as for instance Jones, the arthritic ex-Stock Exchange clerk who is living with his wife and two small children in freezing rooms with no cooking apparatus. Or the unknown untold thousands celebrating Christmas in shelters, the firemen, the soldiers, Stan Lock in Iceland, the conscientious objectors in farms, the lonely mothers and ruined shopkeepers, the city children living in farmhouses.