Humans have been stamping and pressing patterns into objects for a long time. Patterns or seals pressed into clay date back thousands of years, and hammering ingots of metal into patterns as coins appears to have started around 600-700 BCE.

Fragments of carved woodblocks used to print patterns onto silk date to about 200 CE, in Asia. Wood-based paper emerges in China around this same time (200 BCE – 200 CE), and using a carved woodblock to press out the pages of a book dates to about 650-700 CE, in the reproduction of Buddhist scripture.

The technology is simple. Regardless of your medium, parts of a solid, level surface carry ink, which is transferred onto the surface of paper by stamping or pressing.

Although moveable type (ca. 1050) enabled printing of Western languages, with the rich combination of a finite set of letters into infinite words, the pictographic Eastern languages remained more suited to carving out an entire page uniquely, as opposed to carving and sorting, indexing and storing thousands of characters.

The printing press emerges in the mid-1400s, and using carved wooden blocks as the source of impressions was common for a hundred years, until the long era of etching on metal (1500-1800) prior to lithography and offset printing.

Woodblock printing for books and artwork persisted in Asia through the late 1800s, before the era of photo-reproduction changed the world of printing.

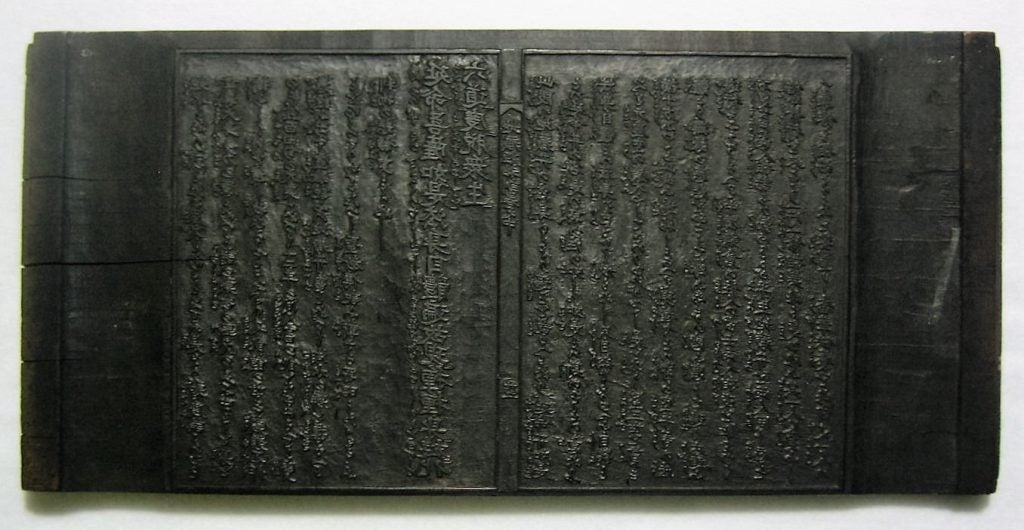

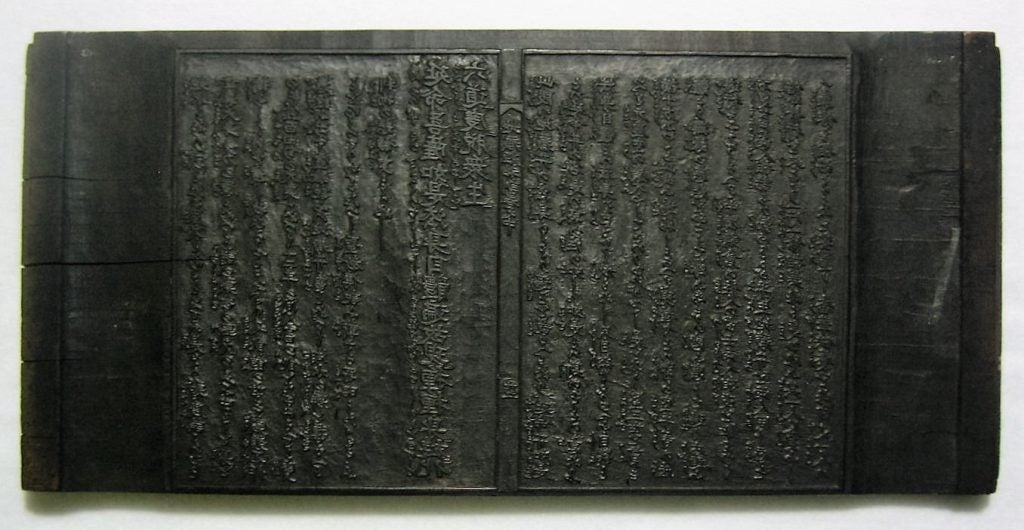

Here is an 1853 Japanese woodblock printing plate that I own.

This is a hard wood block carved on both sides. The printing area is 17.4 x 27 cm (6 7/8 x 10 5/8 inch), with an overall size of the woodblock of 19.2 x 40.5 cm (7 1/2 x 15 7/8 inch), with a thickness of 1.3 cm (1/2 inch). It weighs 720 g (1.6 pounds).

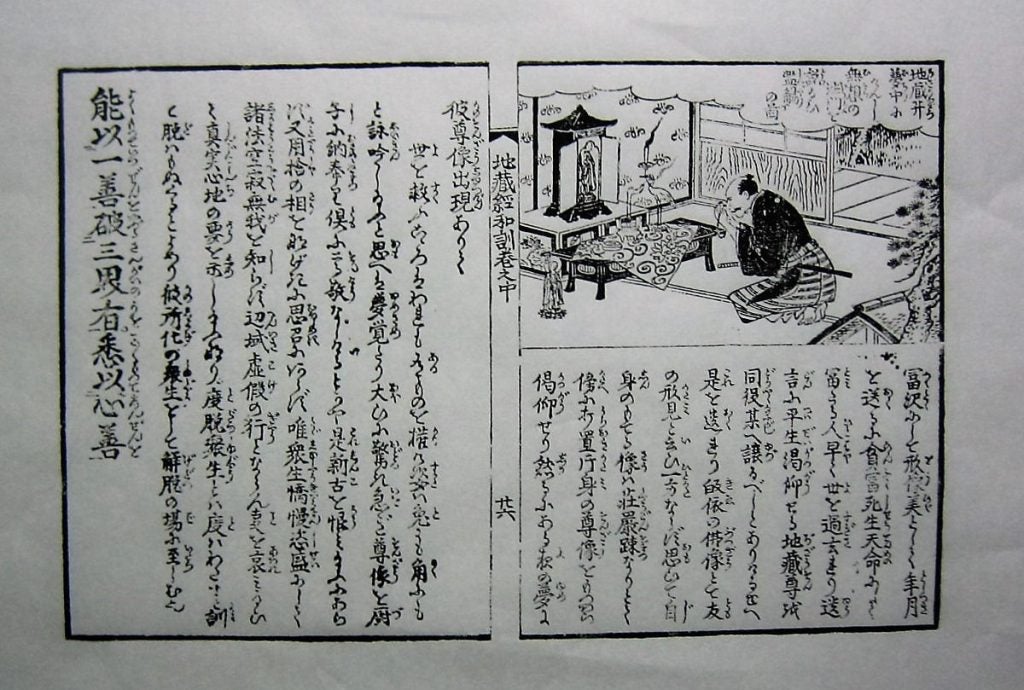

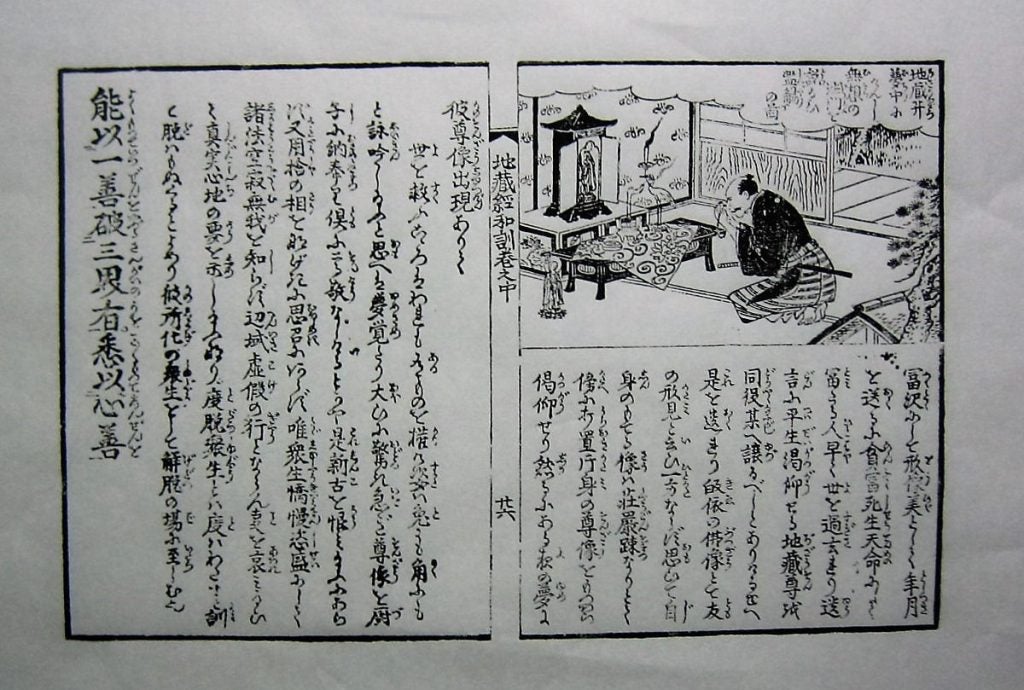

The provenance on this is solidly good because the book is well known. Here is the impression from this plate.

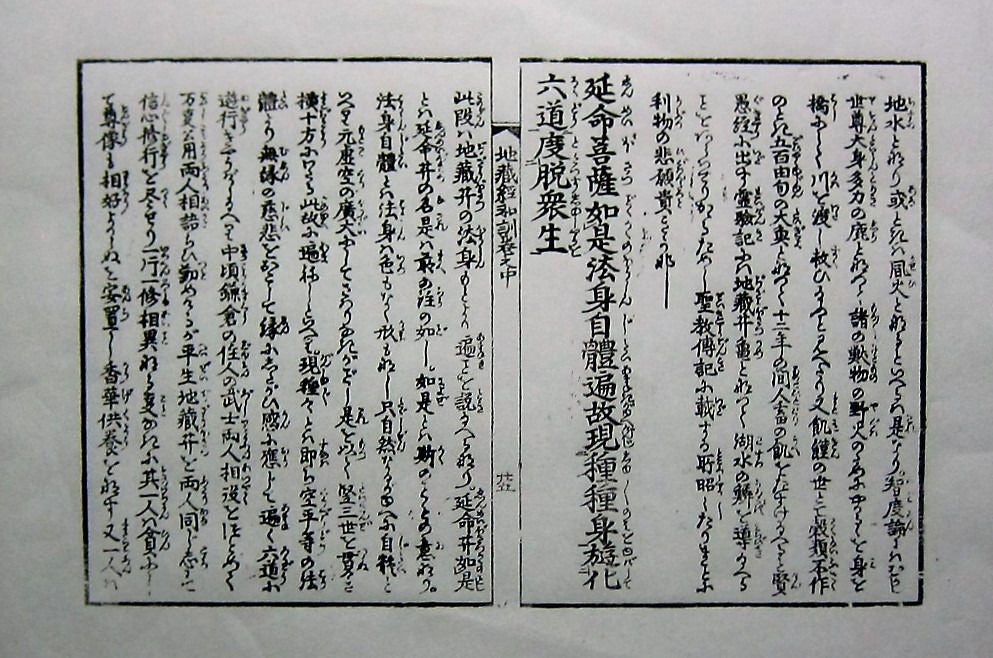

The book title is Enmi Jizokyo Wakun Zue (Sutra of Life-extending Jizo Bodhisattva with Japanese Annotation and Illustration) in 3 volumes; and these are pages 25 and 26 of Volume 2. It was printed by Bokuko and released in September 1853 by the bookseller Haruhoshi Do in Osaka. The editor and commentator was Yomogimuro Aritune, and the illustration artist was Matsukawa Hanzan (1818-1882). The scripture itself was first published in print form around 15thcentury in Japan, and this specimen is one of the first with illustrations and Japanese annotation.

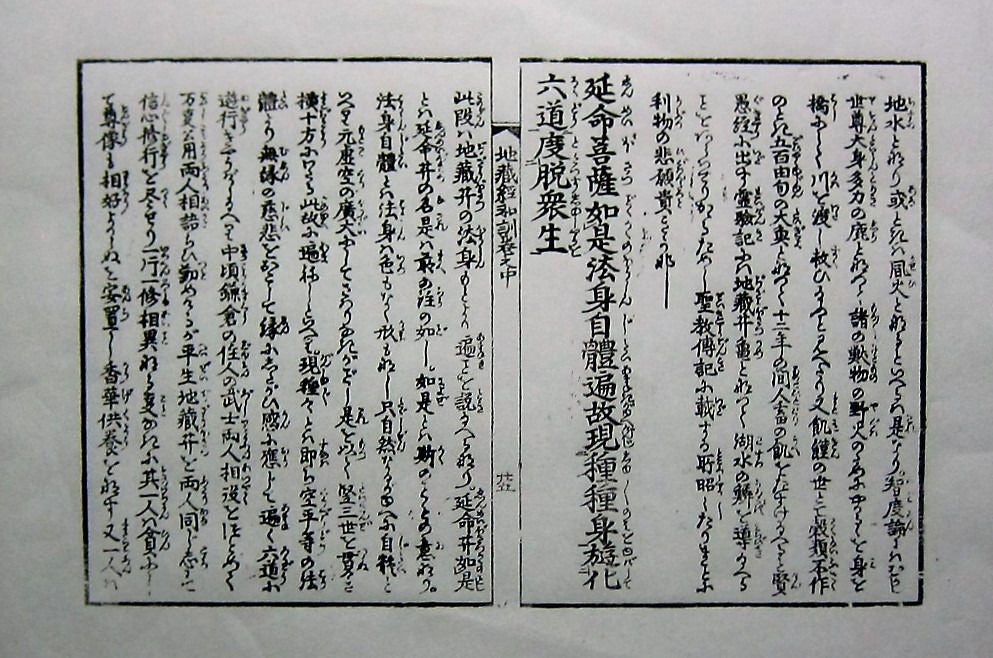

Ksitigarbha is one of the four most important Bodhisattva of East Asian Buddhism, and one of the most loved figures in Japan (called O-Jizo Sama by children in Japan). Many scriptures attributed to him were translated from Sanskrit in China around 700 CE. This particular scripture (Enmi Jizokyo) was claimed to be translated by Amoghavajra (705 – 774), a highly revered Indian monk who spent most of his life in the court of Tang dynasty China.

It begins with a passage claimed to be spoken by the Buddha himself. The scriptures might actually have been originated in Japan since there are certain passages that are uniquely Japanese (e.g., mentioned the legendary Tengu – a heavenly dog). It was very popular with the Samurai of Kamakura period (11th – 12th century) and popular with people of East Asia ever since.

This woodblock printing plate contains one of the important passages with its entire annotation and its companion illustration. The pronunciation of each character was indicated by Hiragana.

It can be translated roughly as: Jizo Bodhisattva is such that he can exhibit his body in variety of forms and would like to save all the souls from all the Six Worlds (including the hell). The annotation included detailed explanation of each word and a story of two Samurai (rich and poor) of Kamakura period with the illustration showing one praying with the Jizo Bodhisattva appeared to him in person.

The other side of the block looks like this.

And the impression from this side looks like this.

Hundreds of thousands of book pages and images were printed in Japan from the period of about 1710-1875.

Still today, you can see the monks at the Sera Monastery, in Tibet, printing scripture, to be sold as souvenirs, from woodblocks. Here are some pictures I took of a monk working at the Sera in 2008, nearby to a storage wall for the woodblocks.

“Janus” (ca. 1985)

“Janus” (ca. 1985)

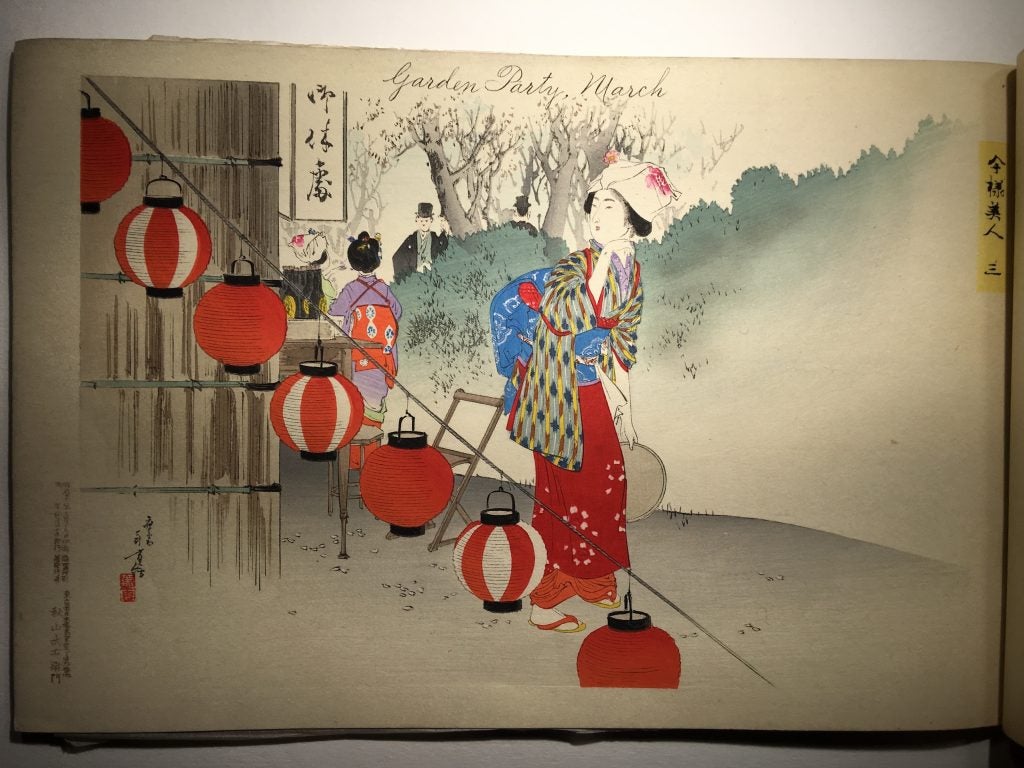

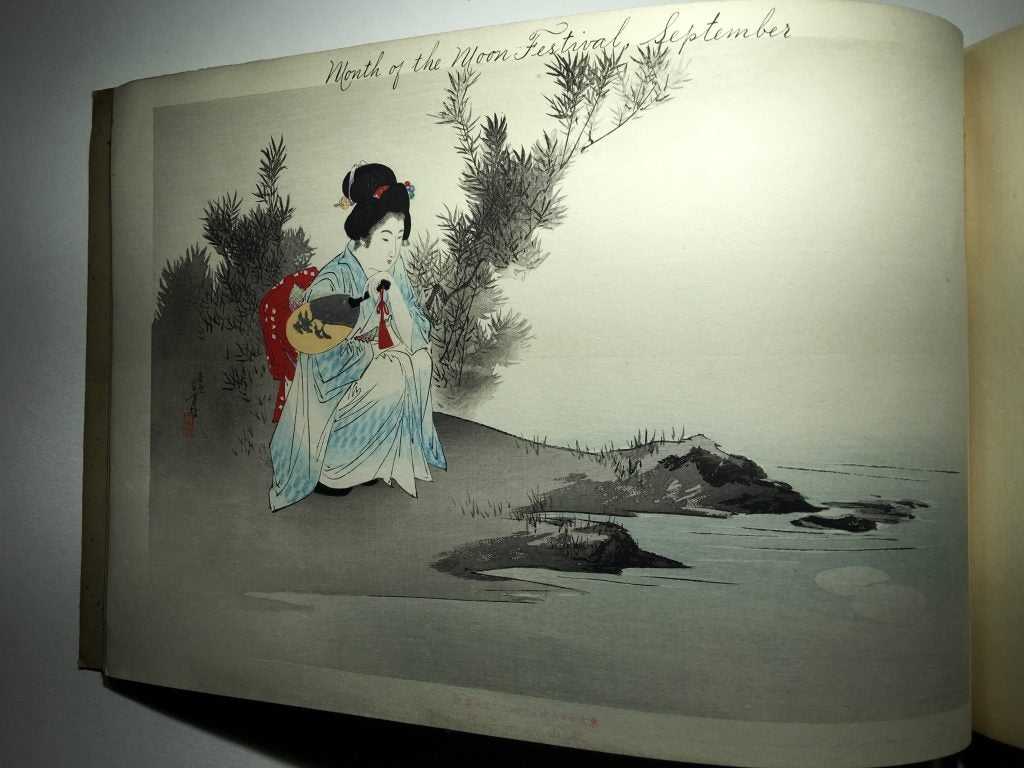

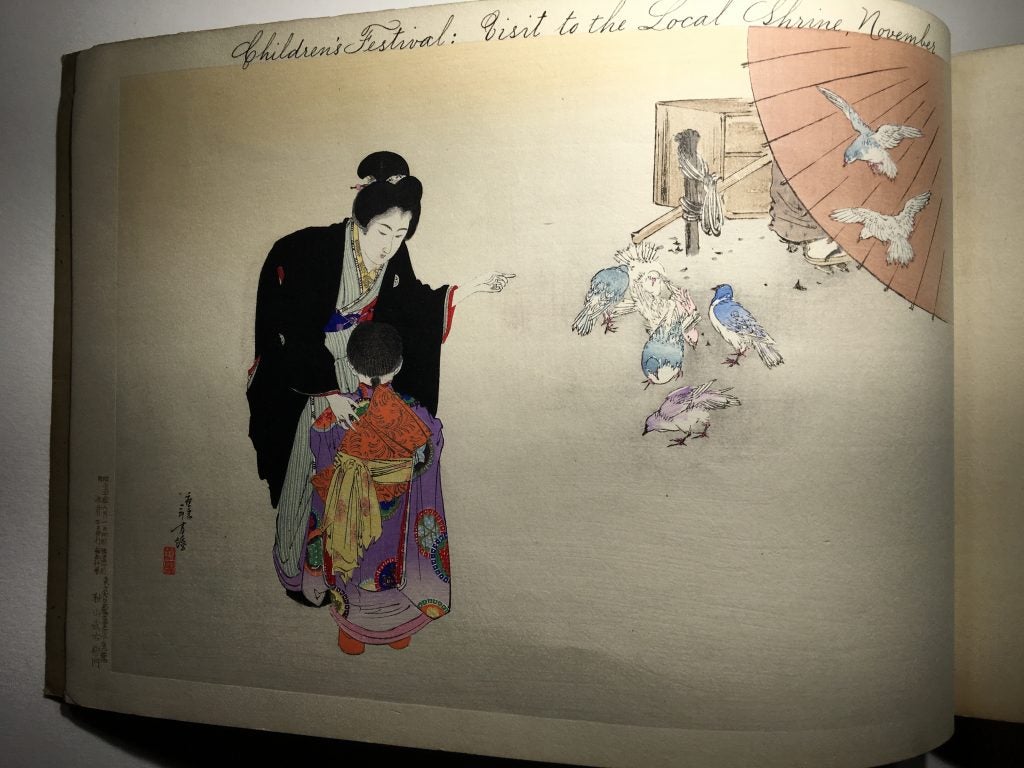

“Modern Beauties” (1898)

“Modern Beauties” (1898)

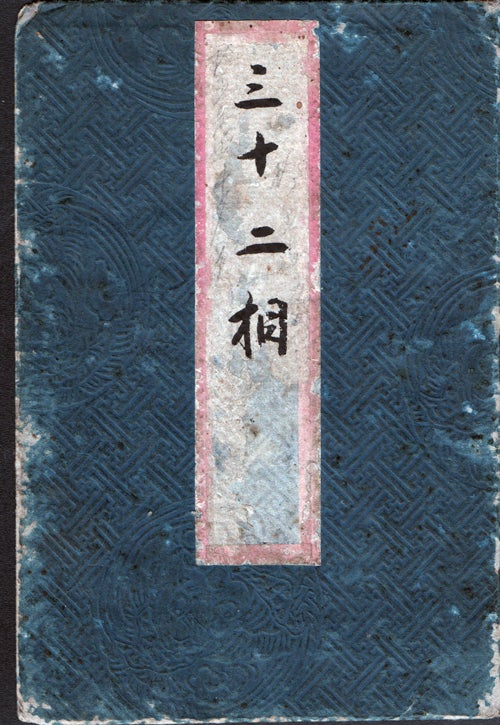

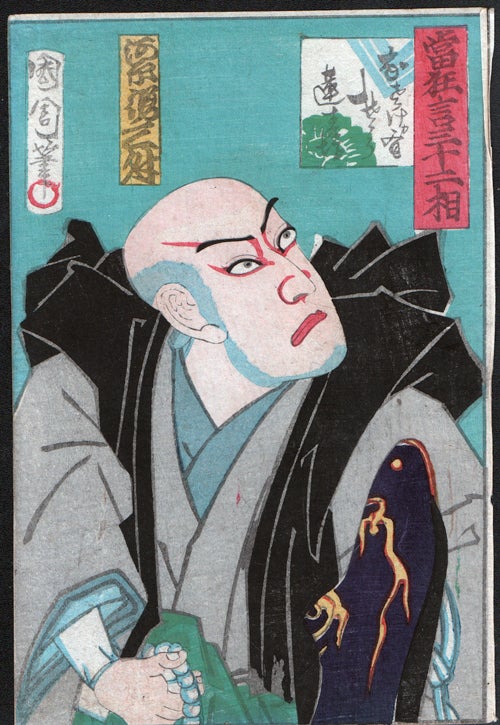

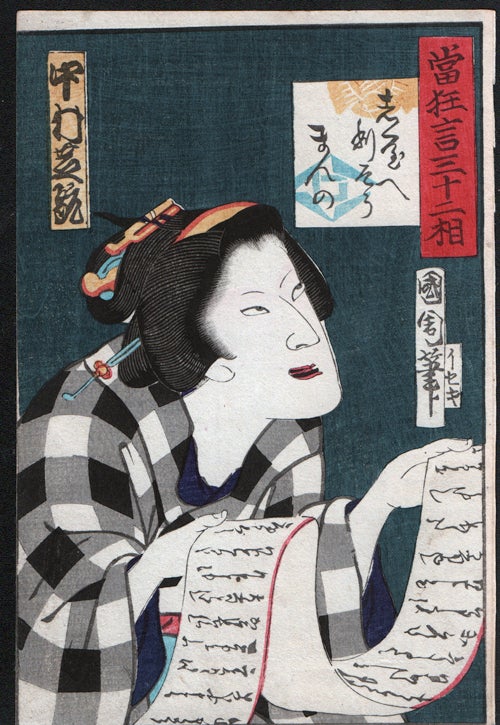

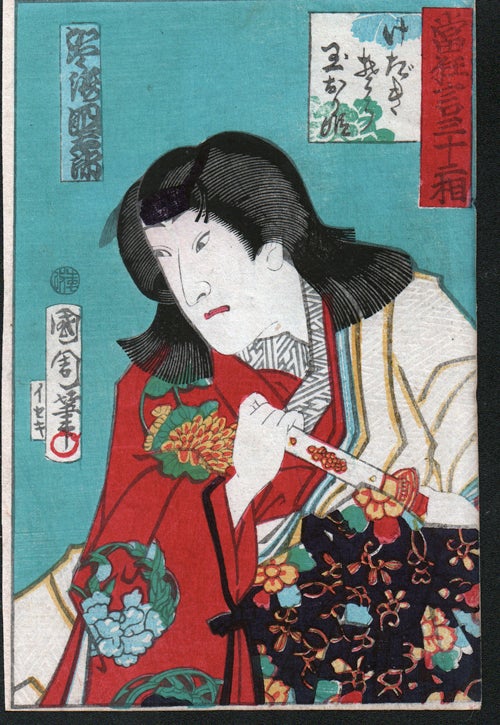

“32 Actors” (ca. 1870)

“32 Actors” (ca. 1870)

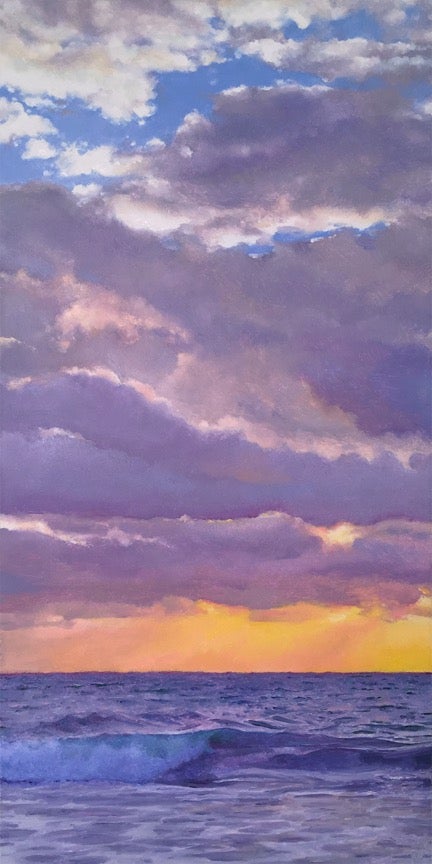

“Pointing to the Moon” (2017)

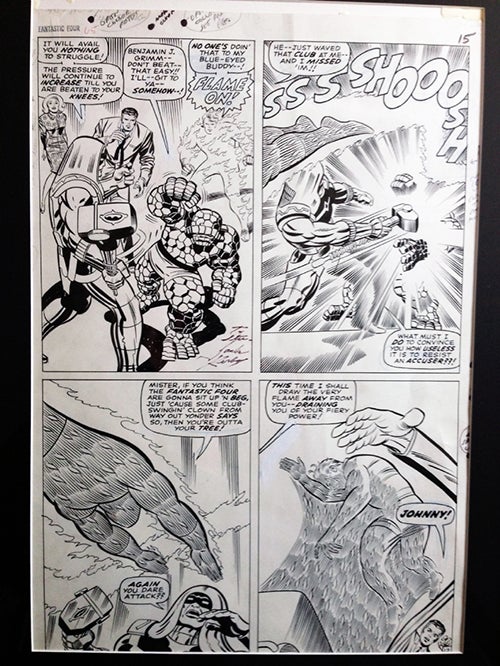

“Pointing to the Moon” (2017) “Fantastic Four 65, page 12” (August 1967)

“Fantastic Four 65, page 12” (August 1967)