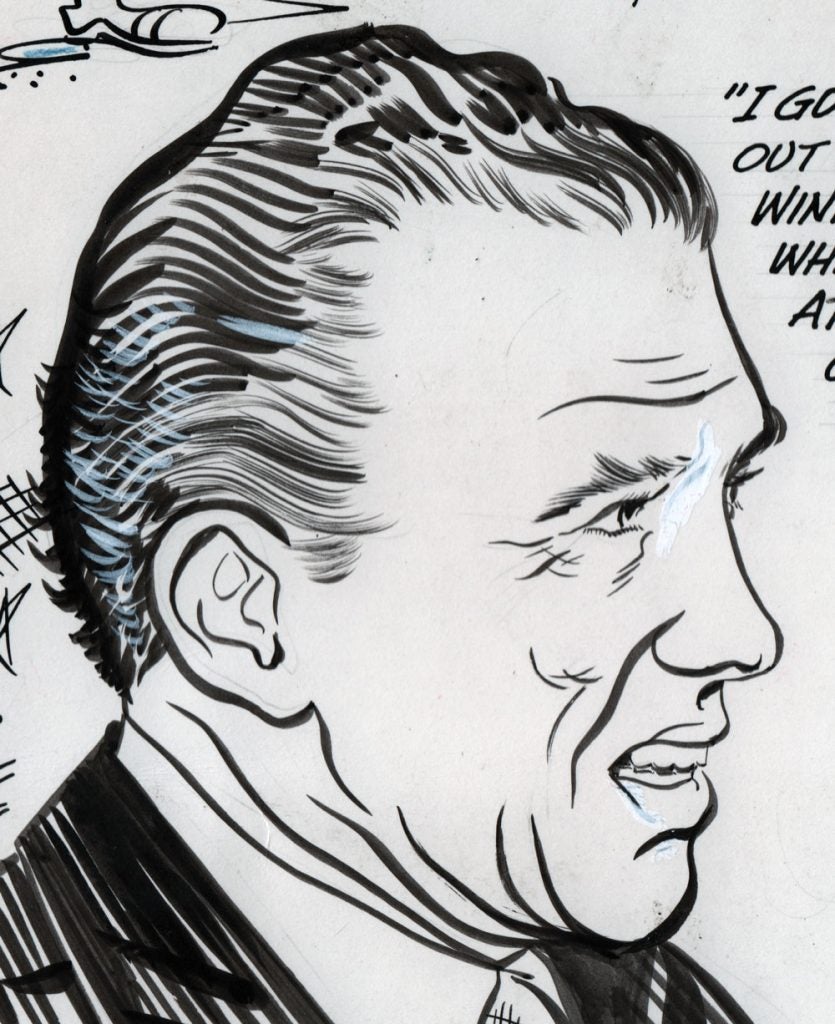

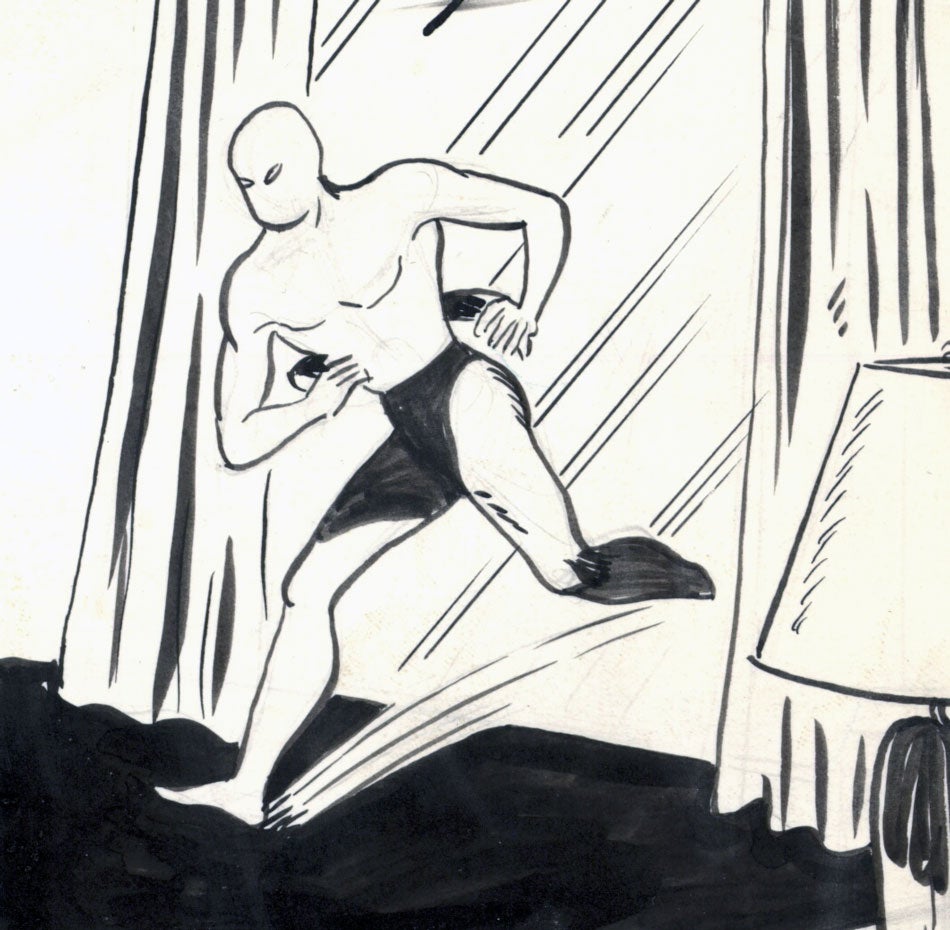

“The Mirror Man” (Tip Top Comics 56, December 1940, p. 36)

“The Mirror Man” (Tip Top Comics 56, December 1940, p. 36)

by Fred Methot and Reg Greenwood (1899-1943)

13.5 x 19.5 in., ink on board

Coppola Collection

The Mirror Man was a super-hero series introduced in the Tip Top Comics anthology in issue 54 (October 1940), by writer Fred Methot and artist Reg Greenwood (who also introduced The Triple Terror characters in this same issue). It ran for 23 issues.

This is from the third Mirror Man issue (page 3 of a 5-page episode).

As Mirror Man, Dean Alder possesses the Mystic Garment, a robe that permits him to use mirrors and other reflective surfaces as his transport, and he uses this to fight crime and evil.

Soon after WWII broke out, both the Mirror Man and Triple Terror characters hung up their spandex and enlisted in the army, becoming military warriors fighting the enemy overseas. The first Mirror Man war story was in Tip Top Comics 71 (March 1942), and the Triple Terror triplet had a spy-adventure and decided to formally enlist at the end of their Tip Top 72 (April 1942) story.

Methot and Greenwood (1899-1943) are credited with The Mirror Man stories through Tip Top Comics 87 (August 1943), which was presumably Greenwood’s last story because he is listed as dying in 1943). The more noted Paul Berdanier (1879-1961) took over The Triple Terror and did one Mirror Man story (TTC 88, September 1943). The rest of the Mirror Man series, which lasts about another year, is not credited except for a couple of stories signed “Singer.” Methot is still thought to have written these, and the artist is referred to as Sam Singer in some places.

Mirror Man saves young Benton from the clutches of the evil Professor, but then takes a bullet. Benton assists him to a mirror, through which the hero passes, rests and recovers from his wound. After Gregg is jailed, Alder is informed of young Tommy Britt being cheated out of money at the Cattail Club, so Mirror Man takes a hand before Tommy’s brother Bob takes on the thugs at the club alone.

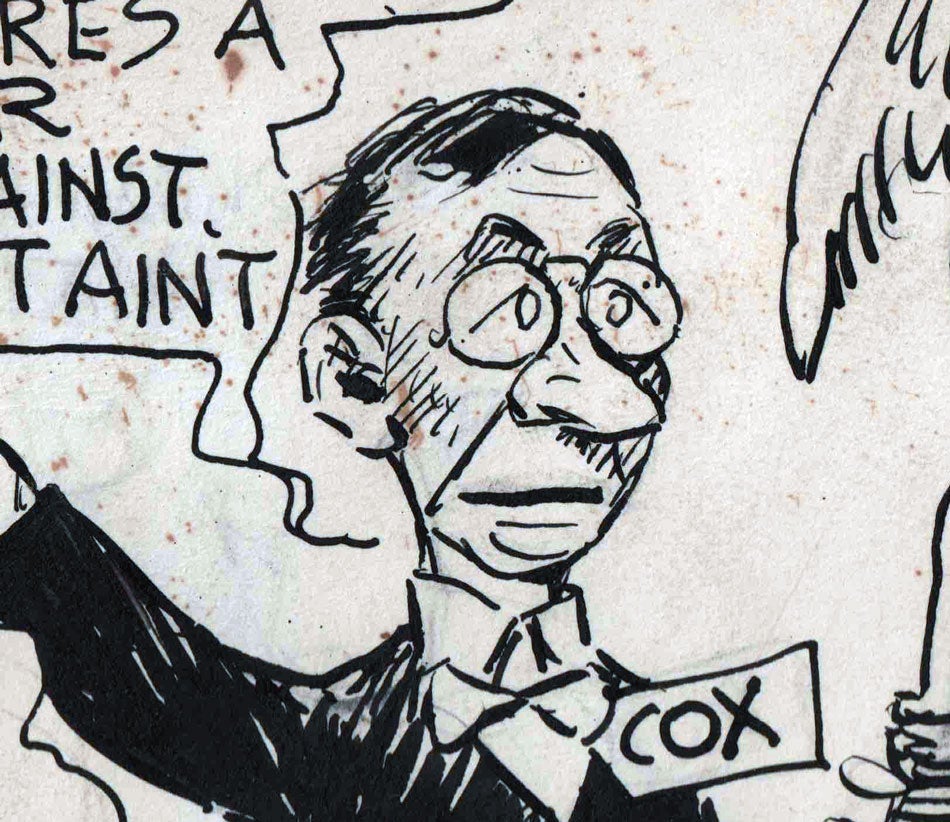

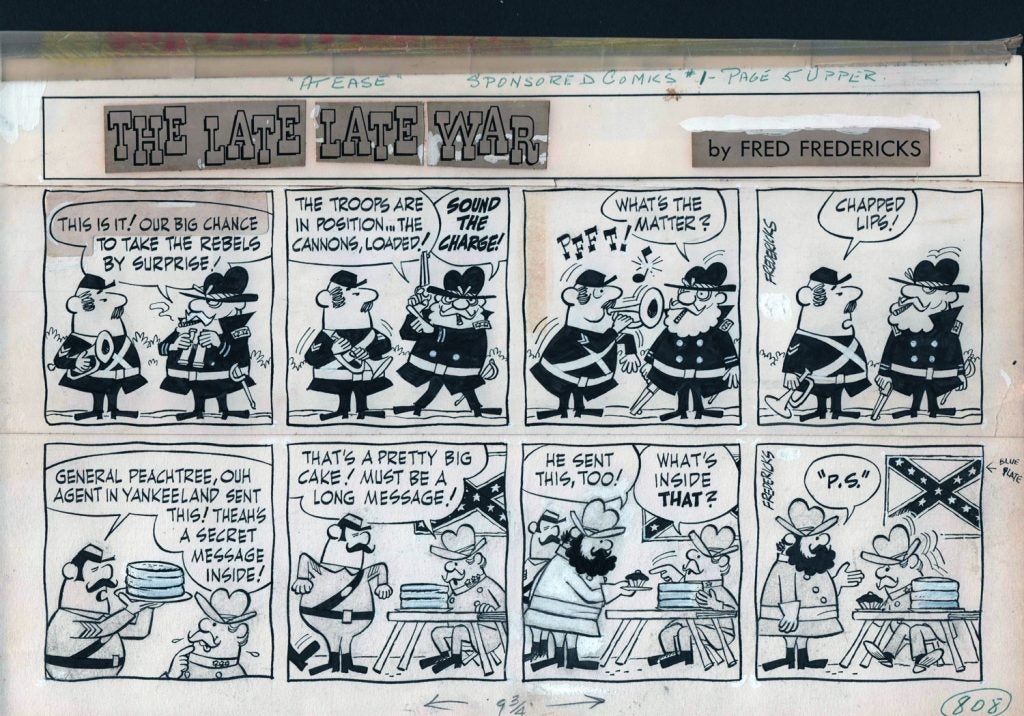

“The Late Late War” (May 14, 1963)

“The Late Late War” (May 14, 1963)

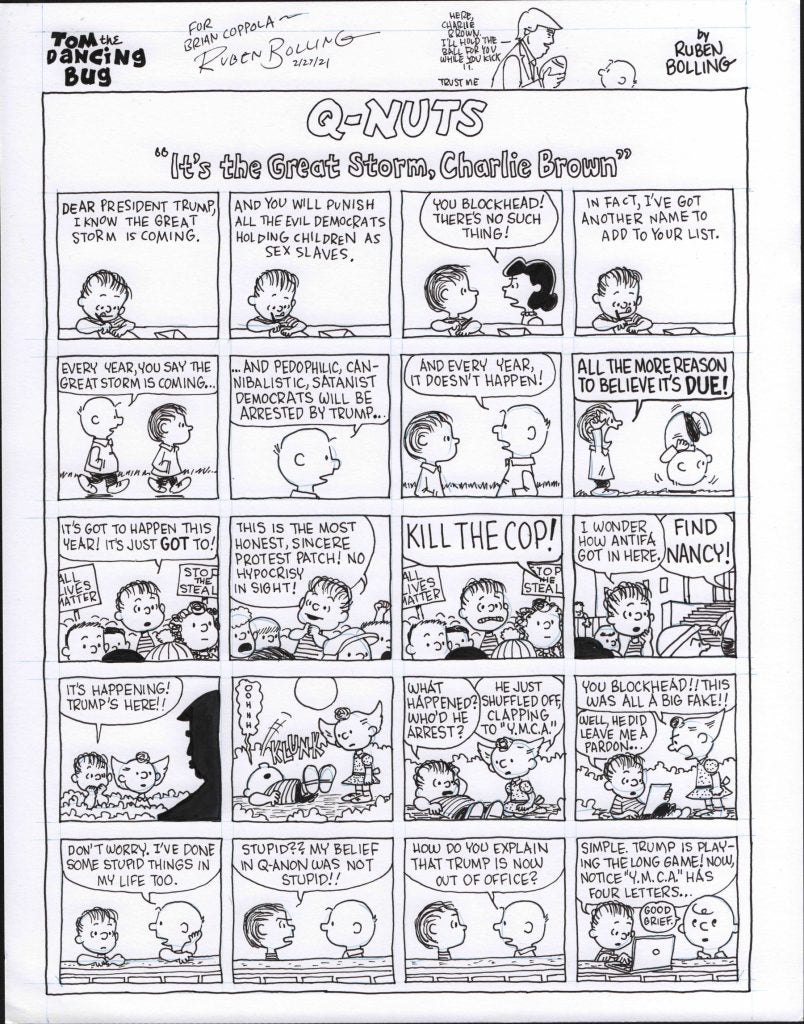

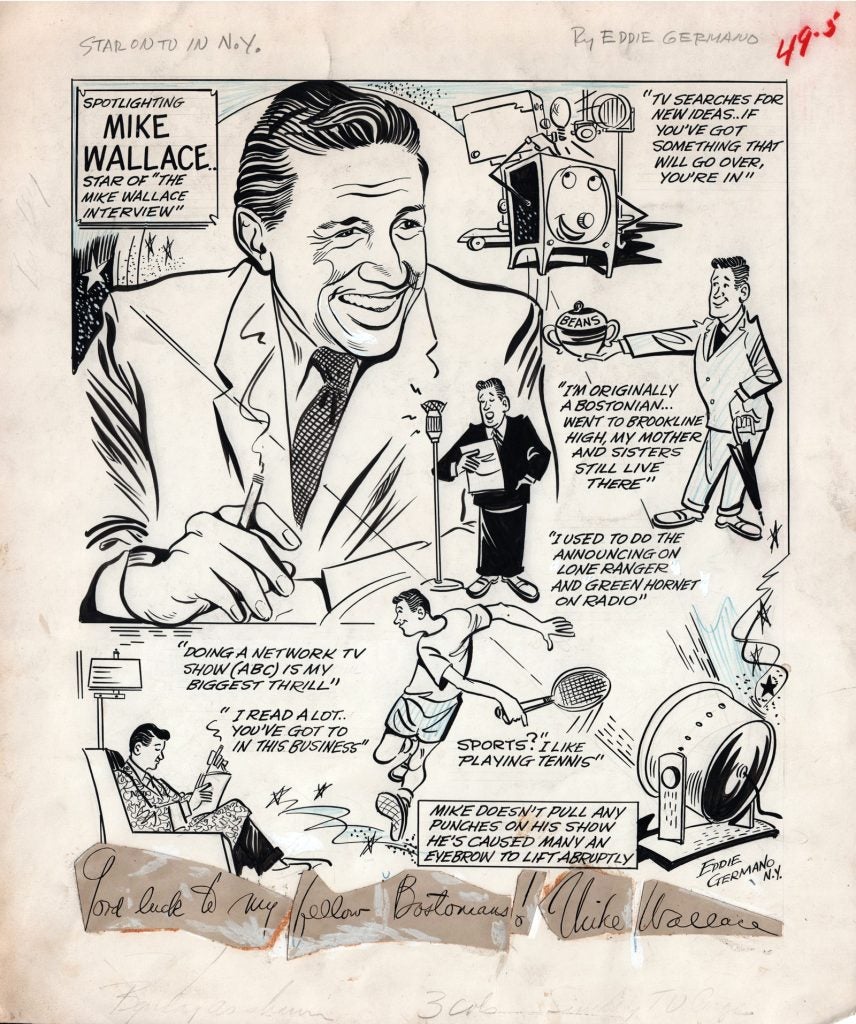

“Mike Wallace (signed) and his Controversial Interviews” (October 10, 1957)

“Mike Wallace (signed) and his Controversial Interviews” (October 10, 1957)

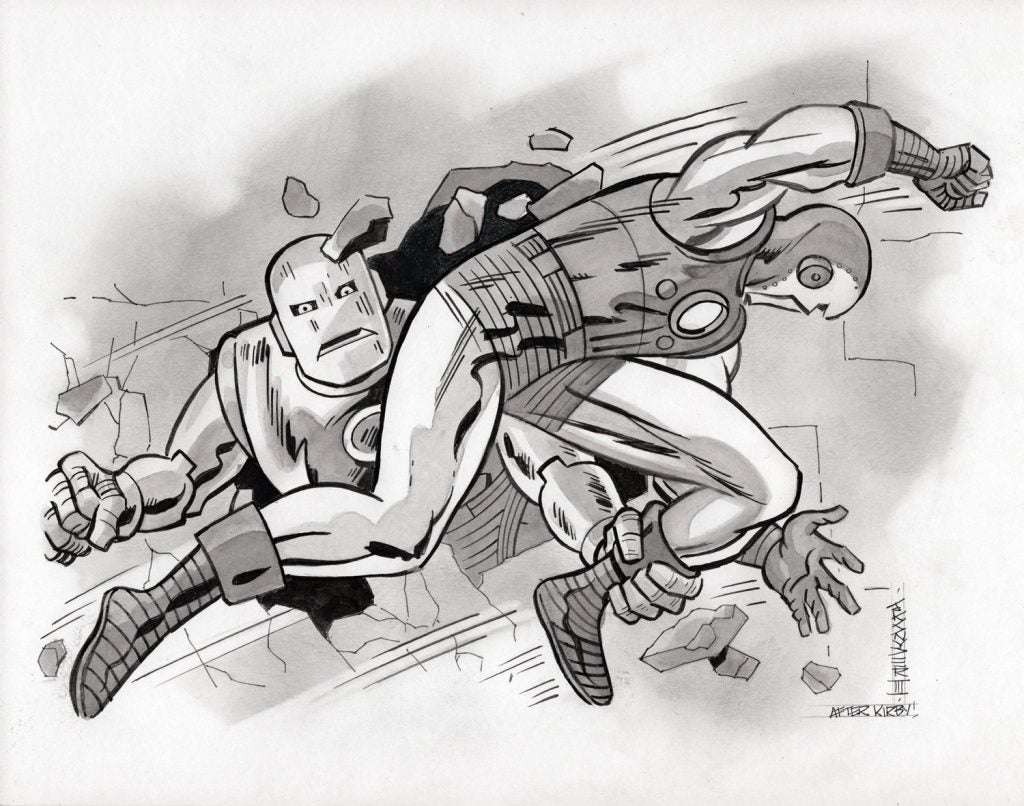

“Ed Sullivan (signed) Celebrates His 9th Anniversary” (September 23, 1956)

“Ed Sullivan (signed) Celebrates His 9th Anniversary” (September 23, 1956)