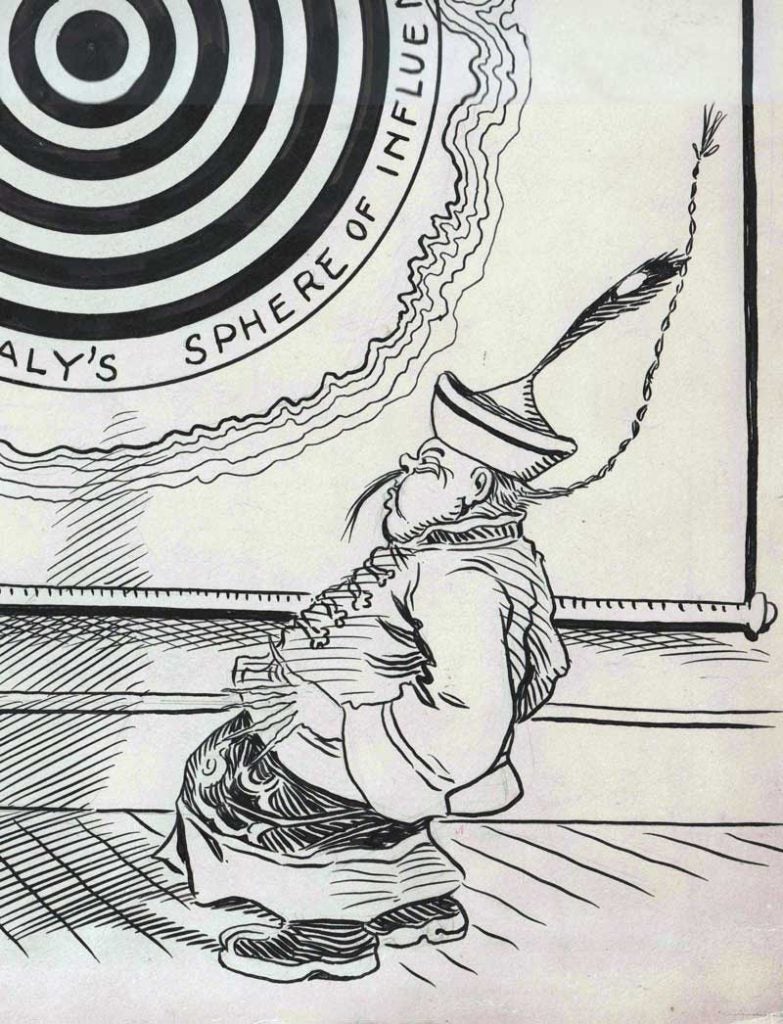

“The Chinese Empire” (September 7, 1899)

by Charles Lewis (Bart) Bartholomew (1869-1949)

16 x 25 in., ink on heavy paper

Charles Lewis (Bart) Bartholomew was a longtime editorial cartoonist for the Minneapolis Journal. He began working as a reporter for the Minneapolis Journal before becoming one of the first daily editorial cartoonists in the world. From 1890 to 1915, he produced an editorial cartoon almost every day, usually published on the front page. A collection of 52 drawings, all from about 1900-1910, is held by Gustavus Adolphus College. This one predates those.

“John Chinaman” was a stock caricature of a Chinese laborer seen in cartoons of the 19th century. John Chinaman represented, in western society, a typical persona of China, depicted with a long queue and wearing a coolie hat. American political cartoonist Thomas Nast, who often depicted John Chinaman, created a variant, John Confucius, to represent Chinese political figures.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term first emerged with British sailors who, uninterested in learning how to pronounce the names of the Chinese stewards, firemen, and sailors who worked as part of their crews, came up with the generic nickname of “John.”

With its weaknesses exposed during the Opium Wars in the 1850s, China began to lose power over its peripheral regions. France seized Southeast Asia, creating its colony of French Indochina. Japan stripped away Taiwan and took effective control of Korea (formerly a Chinese tributary).

The roots of the Boxer Rebellion can be found in the 1895 Euro-centric settlement after Japan’s defeat of China in the Sino-Japan War. This settlement allowed Austria, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Japan, and Russia all to claim exclusive trading rights with specific areas of China. These areas were referred to as “spheres of influence.” Some countries went so far as to claim to actually own the land within its sphere of influence. This already volatile mix was complicated when the United States acquired the Philippines in the 1898 settlement of the Spanish-American War.

The United States had been left out of the Sino-Japan settlement, but now that it had a part of Asia, it wanted a share of China, too. China’s Empress Tsu-Hsi did not want to grant any more spheres of influence to western nations, and rejected the attempts of the United States to gain these trading rights. John Hay, the United States Secretary of State, did not think that people would be in favor of a U.S. war with China, so soon after the Spanish-American War, so he attempted another means to gain influence in China. Hay contacted the governments with Chinese spheres of influence, and tried to persuade them all to share trading rights equally, including the United States.

On September 6, 1899, U.S. Secretary of State John Hay sent notes to the major powers (France, Germany, Britain, Italy, Japan, and Russia), asking them to declare formally that they would uphold Chinese territorial and administrative integrity and would not interfere with the free use of the treaty ports within their spheres of influence in China, as the United States felt threatened by other powers’ much larger spheres of influence in China and worried that it might lose access to the Chinese market should the country be officially partitioned. Although treaties made after 1900 refer to this “Open Door Policy,” competition among the various powers for special concessions within China for railroad rights, mining rights, loans, foreign trade ports, and so forth, continued unabated.

It was in this disorganized squabbling of foreign ownership over Chinese trade that the Boxer Rebellion began. And the Boxer Rebellion was the beginning of the end for Imperial China. In November 1899, under the rule of Empress Dowager Cixi, the secret society the Harmonious Fist (translated as “boxers”) began slaughtering foreigners. The Boxers won the Empress Dowager’s support when eight European countries sent troops. But China lost the conflict, and the West imposed sanctions that permanently weakened Qing rule.

Over the next ten years, numerous revolutionary uprisings occurred throughout China, resulting in the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 under the leadership of Sun Yat-Sen.