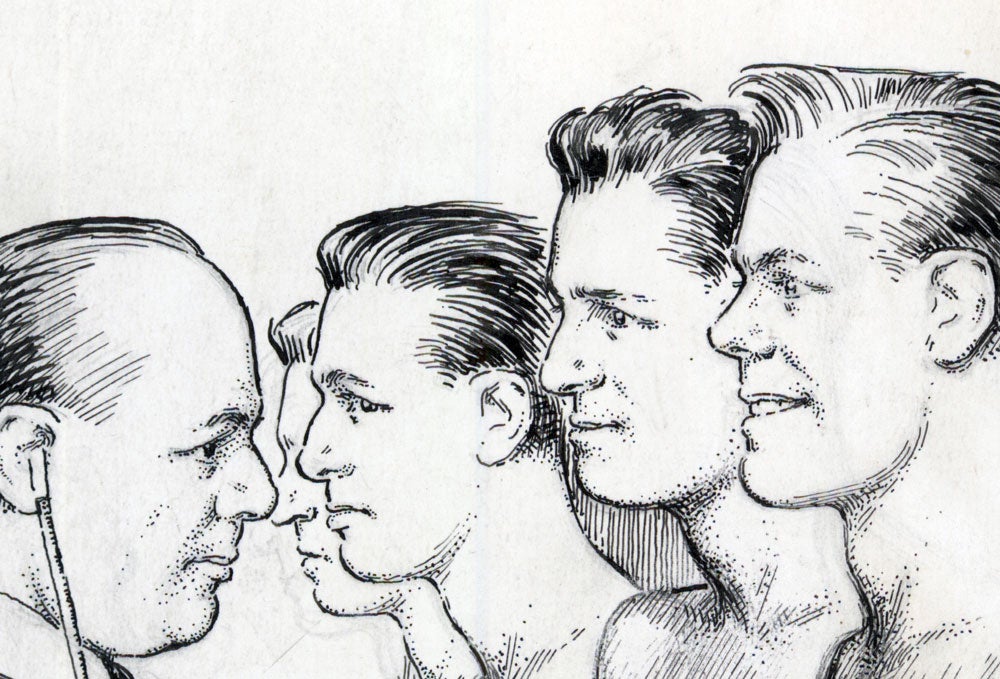

“Fashion Show” (Among Us Mortals, 07/30/1950)

by W.E. (William Ely) Hill (1887-1962)

24 x 19 in., ink on board

Coppola Collection

W.E. (William Ely) Hill was known for his masterful black and white Sunday page, Among Us Mortals, sometimes referred to as the “Hill Page.”

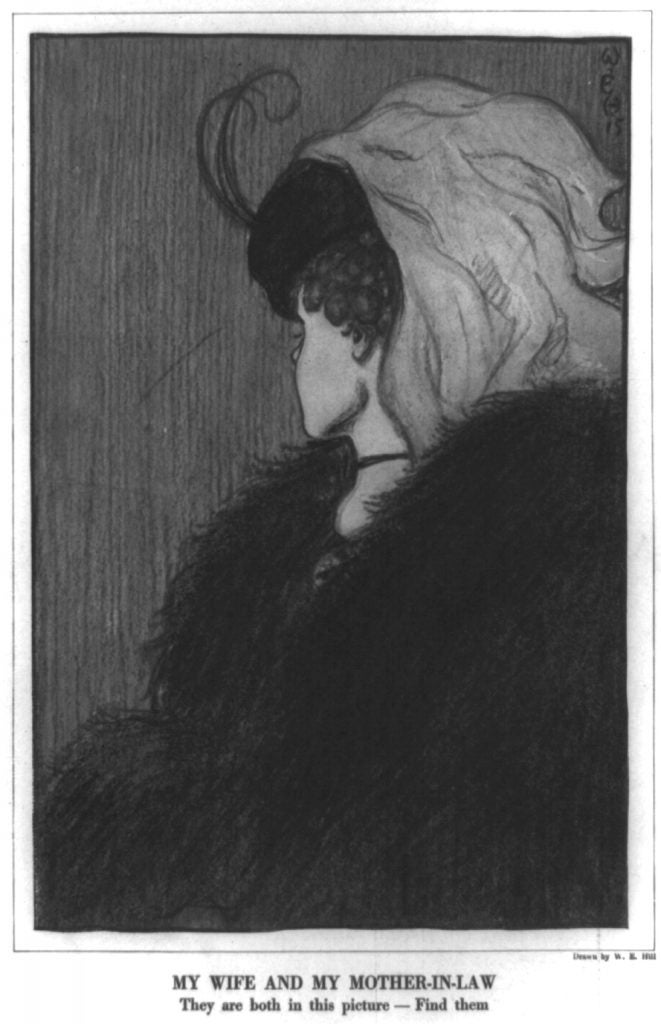

His 1915 drawing for Puck, “My Wife and My Mother-in-law,” is perhaps one of the best-known examples of a dual image–it is a drawing that at once depicts a young woman and an old crone, where the young woman’s chin serves as the nose of the old woman. The image originally appeared on an 1888 German postcard, but Hill’s interpretation is the one that ended up in the psychology textbooks (file under Gestalt).

Hill also drew the dust jacket art for the first editions of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise (1920) and Flappers and Philosophers (1920). Bohemians and artists, commuters and theater-goers all found themselves captured (and sometimes caricatured) in drawings of W. E. Hill.

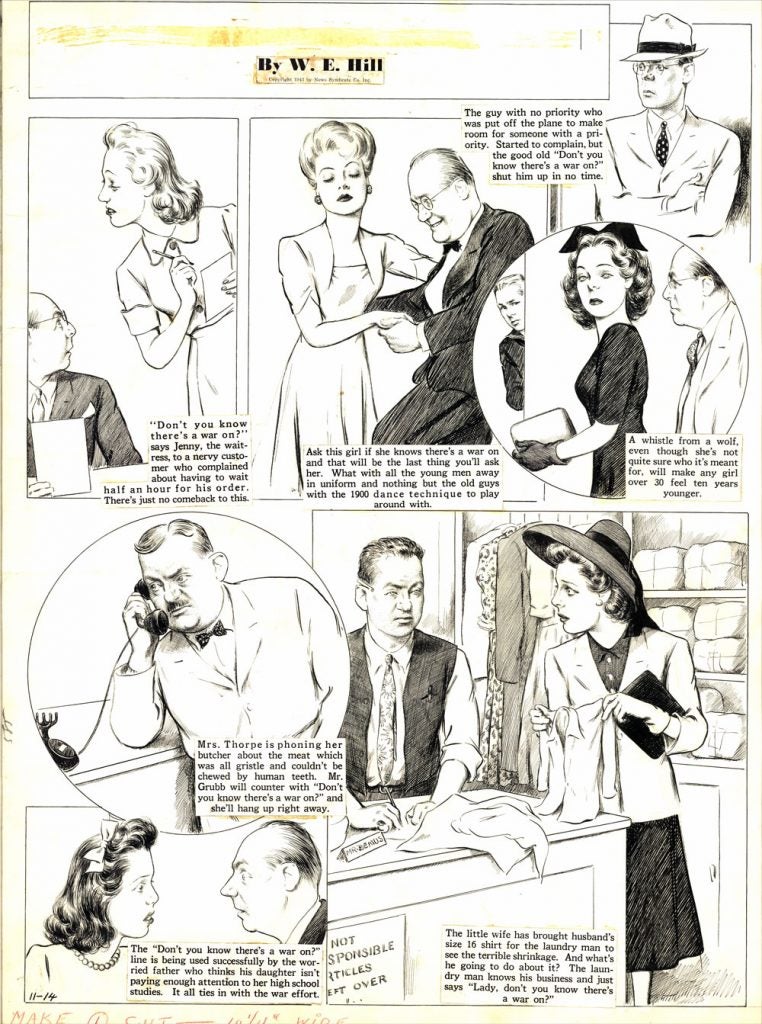

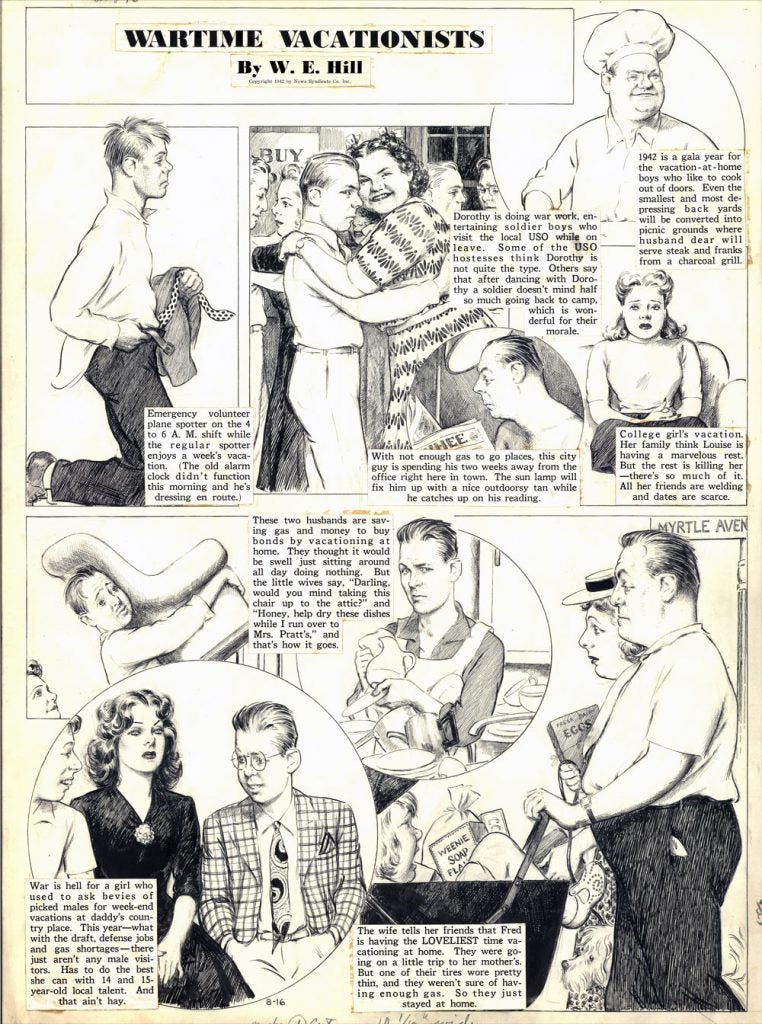

Hill’s Among Us Mortals feature began in 1916, starting out in the New York Tribune. It began syndication by the Chicago Tribune in 1922, and then jointly by the Chicago Tribune-New York Daily News from 1934 until it ended in 1960. Hill was a masterful observer of human beings, and each Sunday page was devoted to a particular slice of observation.

Hill’s work got a lot of attention quite rapidly. Franklin P. Adams writes in his preface to a collected edition of Among Us Mortals (1917): “Hill is popular, by which I mean universal, because you think his pictures look like somebody you know, like Eddie, or Marjorie, or Aunt Em. But they don’t; they look like you. Or if you prefer, like me. He is popular because he draws the folks everybody knows.” The collected volume showcases W. E. Hill’s satirical images of modern Americans, including his take on modern art appreciation.

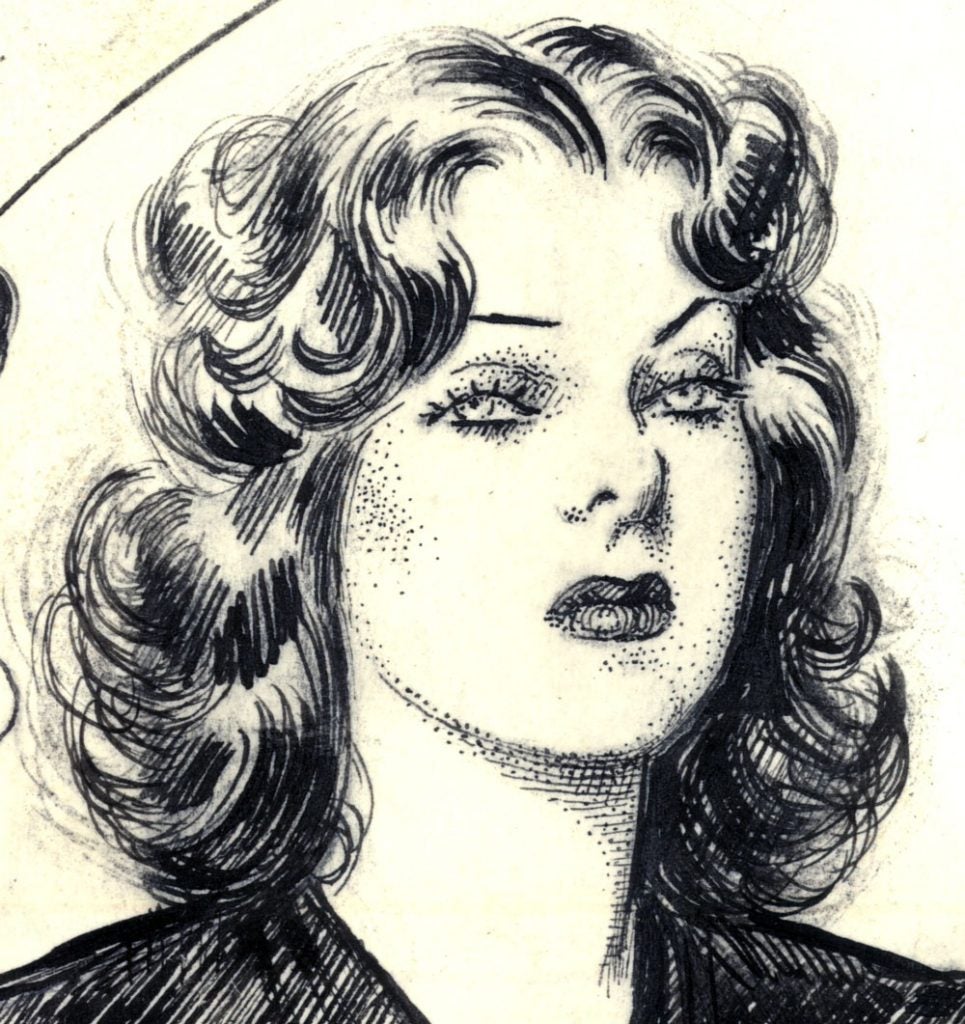

There was no one doing pen and ink artwork in the newspapers like Hill. The original artwork is stunning, with its delicate hatching, cross-hatching, and stippling, and probably did not even translate that will into bleed-heavy newsprint.

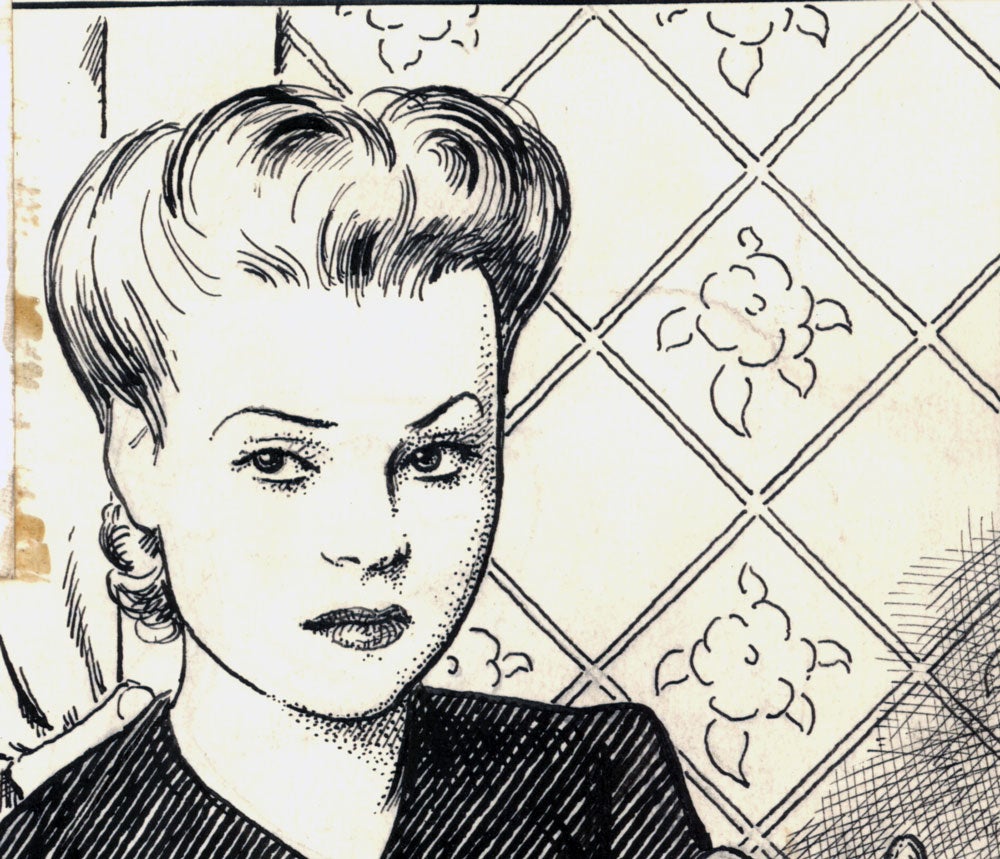

In this July 30, 1950 edition, titled “Fashion Show,” Hill presents a look at various folks, all wearing various types of attire, with comments about each. The details spent on the figures and tones is truly amazing, with lots and lots of delicate pen-work.

I think Hill’s photorealistic style caught people unaware because of the intimacy with which he drew everyday life. It is easy enough to dismiss yourself when the story is a cartoon, but Hill was clearly an observer, a candid camera who recorded images that were not the posed and composed fare of photography.

From a profile and interview with Hill:

Practically no one who sees Mr. Hill without being introduced to him would guess for an instant that this modest and retiring young man is the creator of the most human and true life sketches ever printed in America. From coast to coast and in foreign countries his work is admired for its fidelity to nature and to types. Everyone who has seen his drawings of people one meets in the streets, in the theater or other gathering places, never fails to remark, ‘I’ve seen exactly that type, and the artist must have sketched some one I’ve seen.’

Mr. Hill pictures people at work, at play, on their way to work, at home, at meals, or on picnics. He doesn’t try to make any one handsome who is not handsome, and men and women wearing eyeglasses appear frequently in his sketches, not because he wears them himself and likes to draw them but because he finds these people wherever he goes to faithfully and truly reproduce what he sees.

“I learned very early in my career as an artist that if you stick pretty close to the people you see about you, every day you need not draw on your imagination for types,” said Mr. Hill.

“People, just plain, everyday, commonplace people, alive and in motion fascinate me far more than anything else in the world,” he continued. “They look and dress, and do everything that they could be imagined doing, and they are everywhere that there is anywhere to be. When I made my first sketch of people as I really found them, I had no idea of keeping it up. That was simply one day’s work. I remember the first sketch very distinctly. It was made only a year and a half ago and was a few glimpses at the Easter parade in New York City. When that was printed it suggested another sketch of human life as it is and every sketch suggests a great many others. Human nature is an exhaustible subject and a man might draw types of men, women and children for a hundred years and still not scratch the surface of his subject.”

“I have come to Washington because life here is very different from anywhere else in the United States and types are to he found here which could not be found in any other city in the country. The vast army of Government employees rushing to their work, the crowds fighting to get on already overcrowded street cars, the blank look on the voteless inhabitants of the city, the rich and the poor, the humble and the great mingling together on your streets, the omnipresent soldier, sailor and marine; the children of the rich playing in the parks, the visitors at the Capitol, the tourists, the scenes at markets, all hold a tremendous interest for me and doubtless would for any one coming to Washington for the first time.Selection and elimination will be my only trouble here, for there are a vast number of types I have not seen before.”

One of the cool things about almost all of this original art is how much richer, interesting and more detailed it is compared to when it was printed. Hill has the advantage of at least having his work printed as a full page (still reduced from the 24 x 19 in original, but not compressed to nothing). The art would be photographed, photo-reduced, and a negative used to etch a metal plate. The ink was water-based, the paper was not scrupulously dry, and newsprint is hardly meant to hold a sharp line anyhow – it is more like a napkin, meant to absorb quickly (emphasis on quickly). Hundreds and hundreds of fine lines and cross-hatch gradations would end up as a gray blur.

I am not really honoring too much with these 72 dpi images, either. But here is how that page appeared in print, from a newspaper archive.

Some detail from the original art: