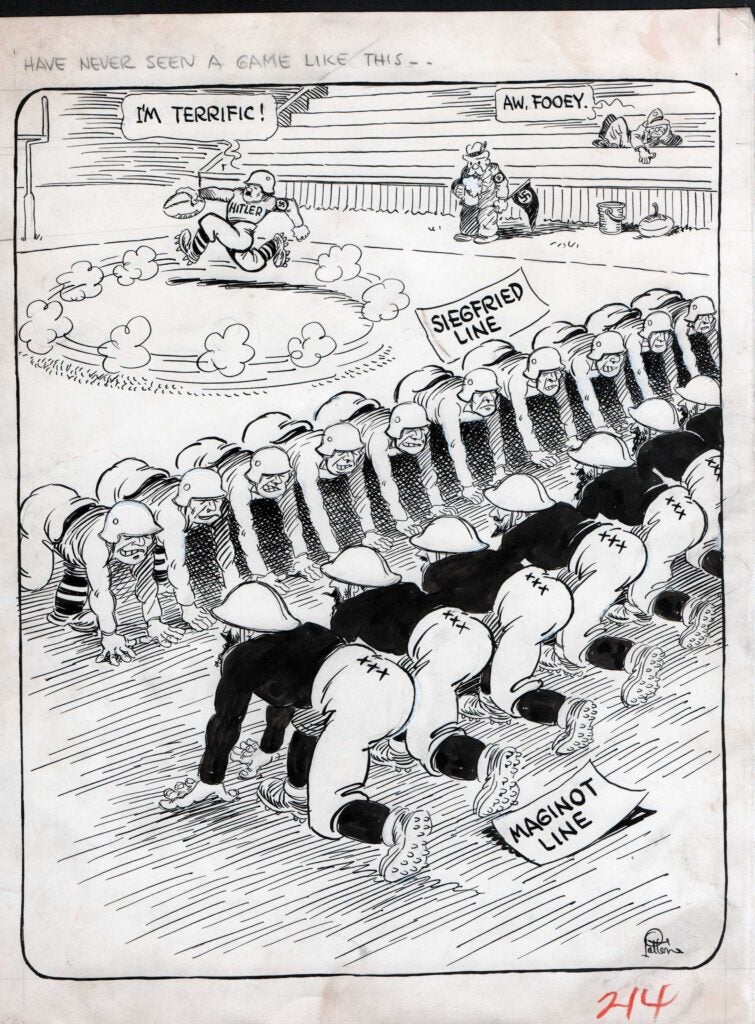

1941.08.01 “Up to His Old Tricks.”

by Wallace Heard Goldsmith (1873-1945)

10 x 13 in., ink on board

Coppola Collection

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Author_talk:Wallace_Heard_Goldsmith

Goldsmith was a Boston institution, working over his long career at the Herald, the Post, and the Globe. This editorial cartoon is from his 25-year period at the Post.

At the turn of the century, the Boston Herald just couldn’t make up its mind whether it wanted to run a syndicate. Their homegrown comic section was born and died at least four different times. The Adventures of Little Allright came in the third version of their Sunday section and ran from March 6 to June 26, 1904. There really wasn’t much to set the strip apart from any other kid strip — the starring kid saying “all right” a lot seems an almost ridiculously weak hook. Goldsmith took the dubious credit for this stinker. The strip was rebooted as Little Alright (the second ‘L’ was dropped), and ran from November 11 1906 to April 14 1907. He was well known for illustrating Oscar Wilde’s “The Canterville Ghost.”

Baron Münchhausen is a fictional German nobleman created by Rudolf Raspe in 1785. The character is loosely based on a real baron, Hieronymus Karl Friedrich, Freiherr von Münchhausen. The real-life Münchhausen fought for the Russian Empire in the Russo-Turkish War of 1735–1739. Upon retiring in 1760, he became a minor celebrity within German aristocratic circles for telling outrageous tall tales based on his military career. After hearing some of Münchhausen’s stories, Raspe adapted them anonymously into literary form. The book was soon translated into other European languages.

In 1941, Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels ordered the production of a filmed version of Münchhausen’s exploits. Münchhausen represented the pinnacle of the Goebbels’ Volksfilm style of propaganda designed to entertain the masses and distract the population from the war, borrowing the Hollywood genre of large budget productions with extensive colorful visuals. The release of the Technicolor film, The Wizard of Oz in the United States was a heavy influence for Goebbels. Münchhausen was the third feature film made in Germany using the new Agfacolor negative-positive material.

The film’s production began in 1941, with a big public fanfare, and an initial budget of over 4.5 million Reichsmarks that increased to over 6.5 million after Goebbels’ intentions to “surpass the special effects and color artistry” of Alexander Korda’s Technicolor film The Thief of Bagdad.

The editorial “Up to His Old Tricks,” is more of a commentary on Goebbels and the disinformation campaigns taken from the headlines of the recent times.