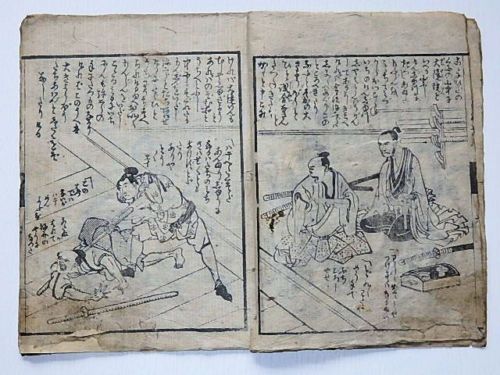

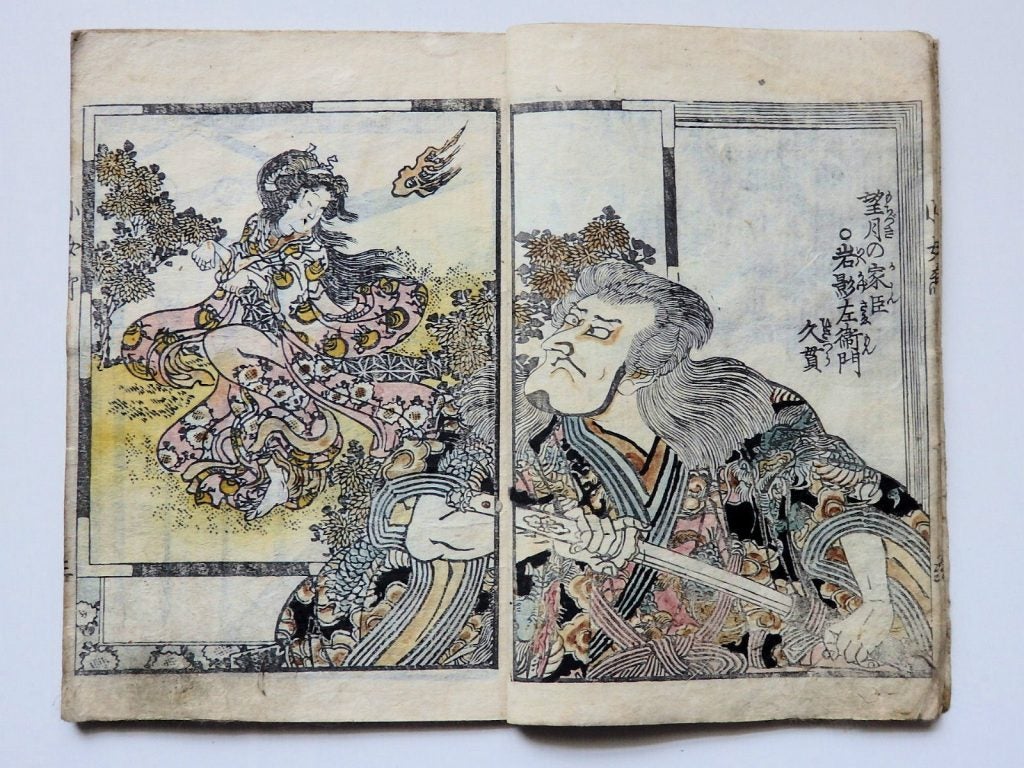

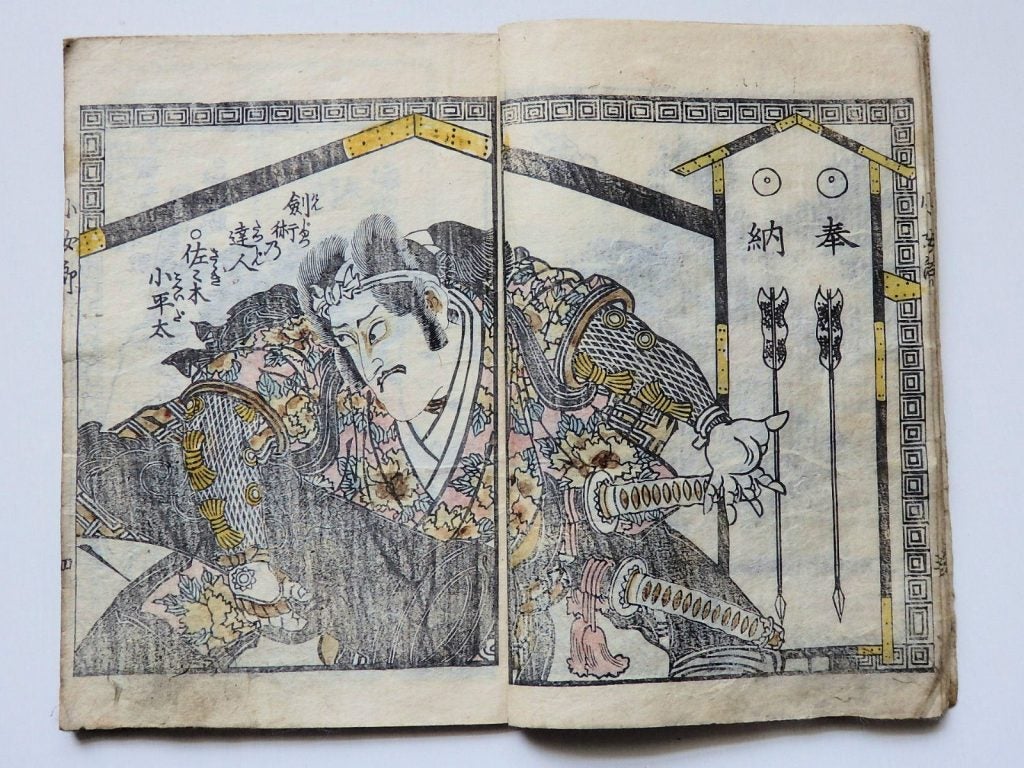

“Jiraiya Goketsu Monogatari” (# 7, pp. 10-11), ca. 1850

“Jiraiya Goketsu Monogatari” (# 7, pp. 10-11), ca. 1850

hanshita-e artist: Kanwatei Onotake

8.5 x 6 inch pages, woodblock print book

Coppola Collection

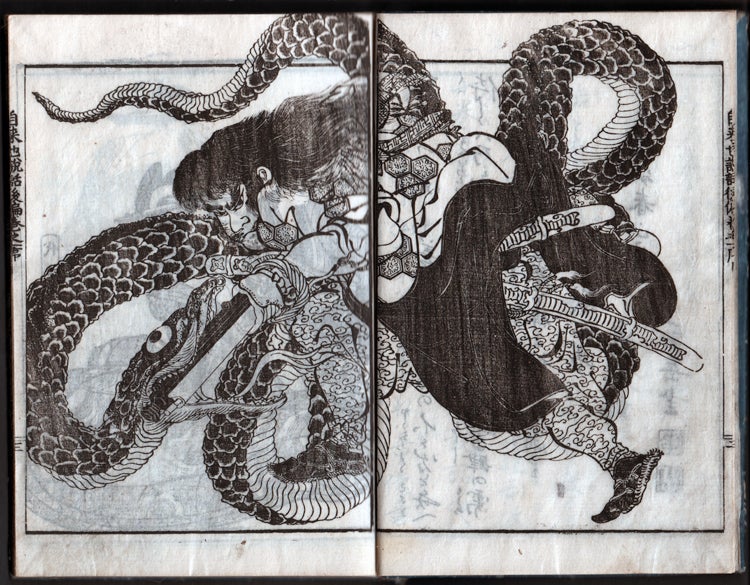

Jiraiya (“Young Thunder”) is the toad-riding character of the Japanese folklore Jiraiya Gōketsu Monogatari(The Tale of the Gallant Jiraiya). The story, first recorded in 1806, was adapted into a mid-19th-century serialized novel (43 installments, 1839-1868) and a kabuki drama, based on the first 10 installments, by Kawatake Mokuami, in 1852. In the 20th-century, the story was adapted in several films, in video games, and in a manga.

Jiraiya is a ninja who uses shapeshifting magic to morph into a gigantic toad. Heir of the Ogata clan, Jiraiya fell in love with Tsunade, a beautiful young maiden who has mastered slug magic. His arch-enemy was his one-time follower Yashagorō, also known as Orochimaru, a master of serpent magic.

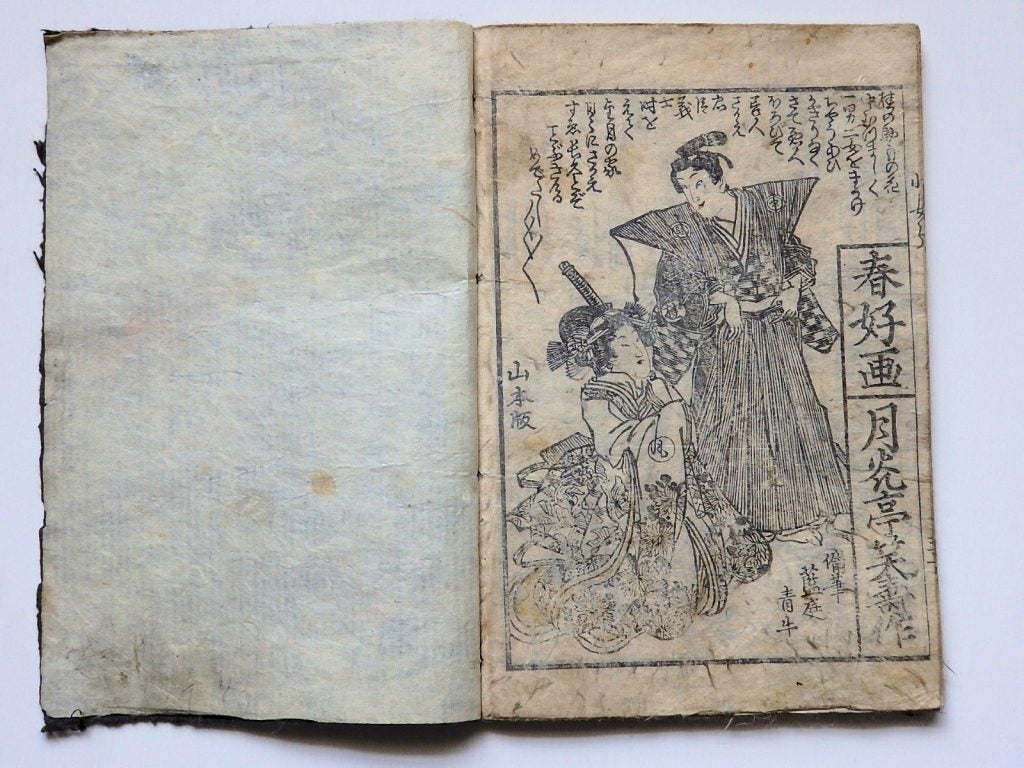

Here is an image of Tsunade, one of the three legendary ninjas in this story. She can summon slugs into battle.

Books printed by carved woodblocks were all hand-printed and limited to a print-run that was determined by the fidelity of the woodblock used to page the pages.

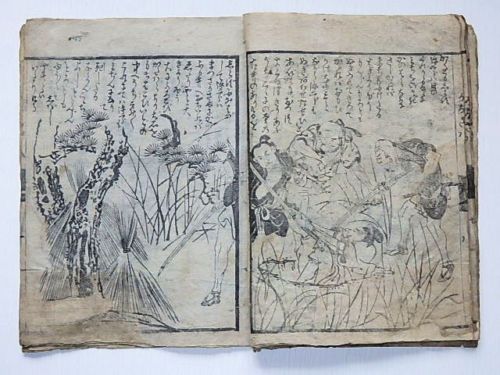

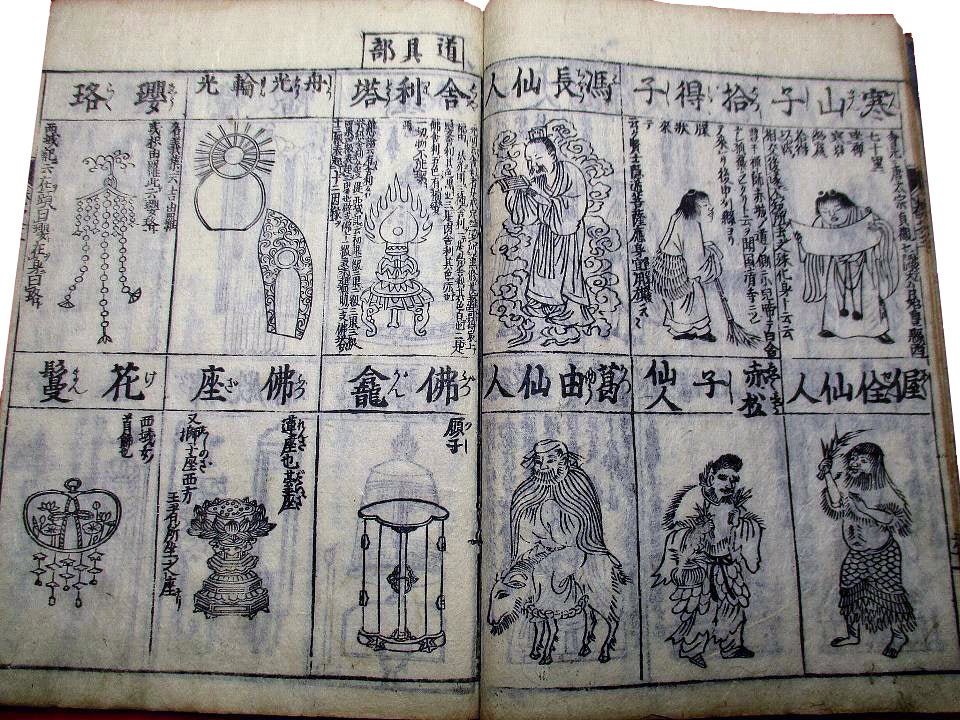

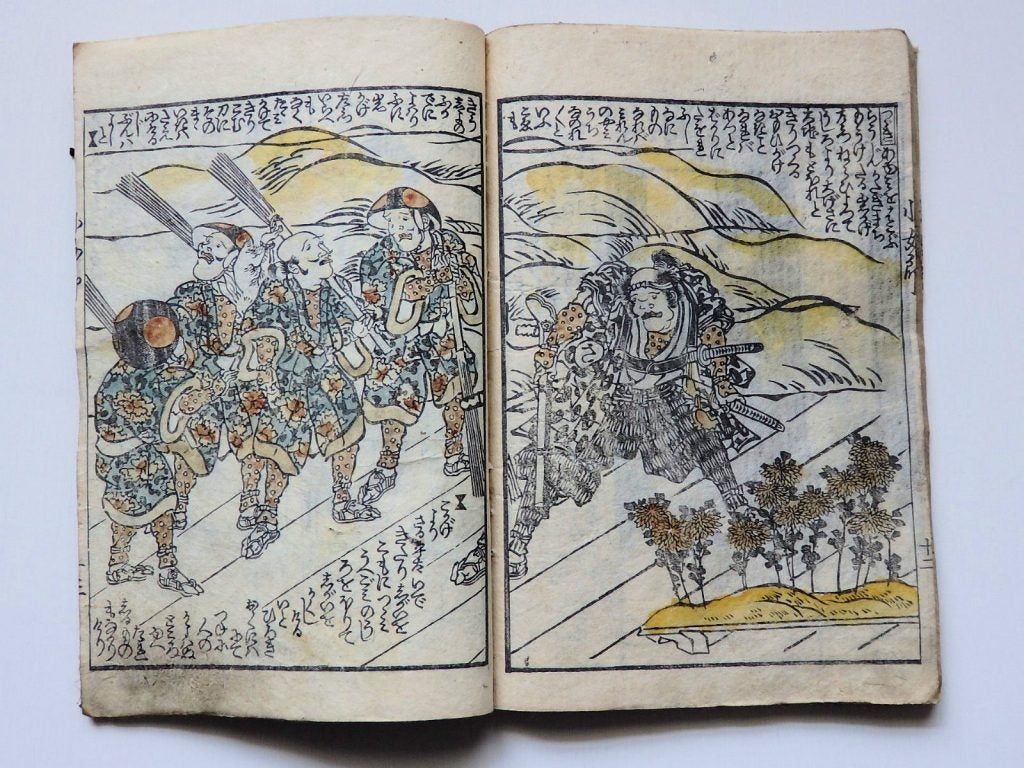

“Jiraiya Goketsu Monogatari” (# 8, pp. 2-3), ca. 1850

“Jiraiya Goketsu Monogatari” (# 8, pp. 2-3), ca. 1850

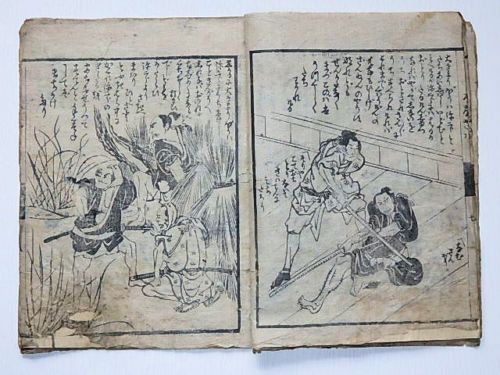

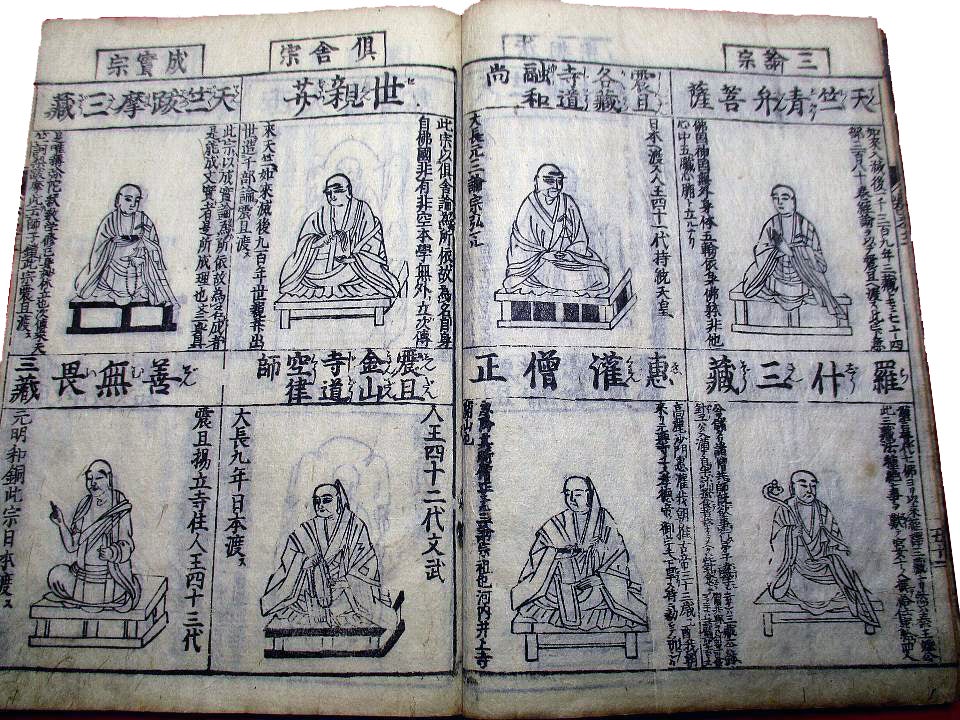

“Jiraiya Goketsu Monogatari” (# 7, pp. 4-5), ca. 1850

“Jiraiya Goketsu Monogatari” (# 7, pp. 4-5), ca. 1850

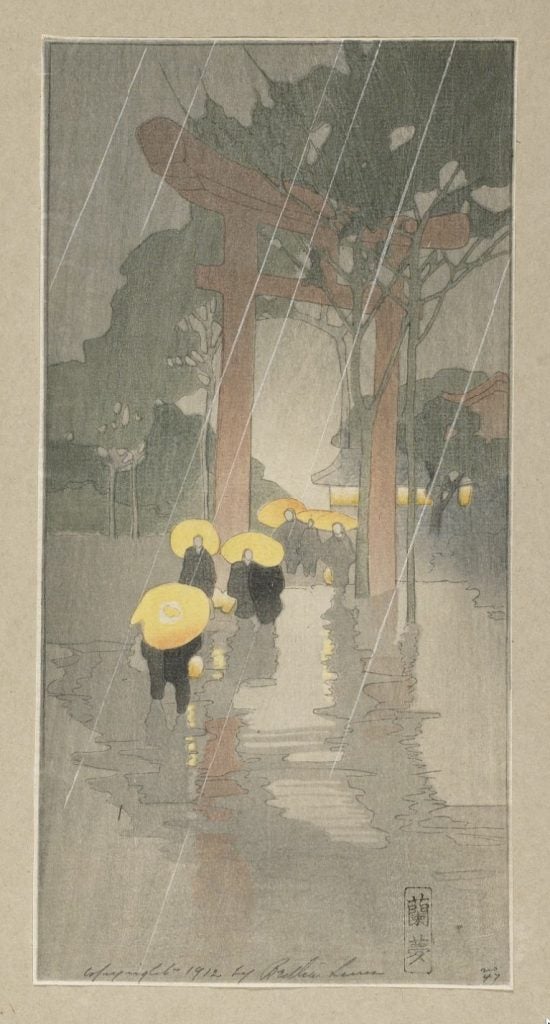

“Temple Gate” (1913)

“Temple Gate” (1913)

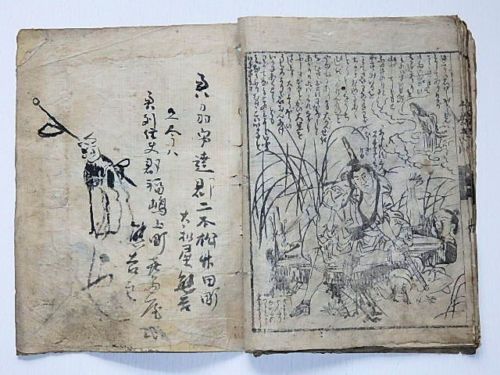

“Kojorokitsune Tebiki-no-Adauchi” (1822)

“Kojorokitsune Tebiki-no-Adauchi” (1822)

“Kinsei Jinbutsushi Hanai Oume” (08/20/1887)

“Kinsei Jinbutsushi Hanai Oume” (08/20/1887) “Kanazawa Yajiro Kaikokukidan” (1805)

“Kanazawa Yajiro Kaikokukidan” (1805)