Previously… this point about reporting percentages.

Previously… this point about reporting percentages.

In a recent essay, UCSB’s Robert Samuels began “Now that more than 75 percent of the instructors teaching in higher education in the United States do not have tenure, it is important to think about how the political climate might affect those vulnerable teachers.” And throughout the first paragraph, these instructors are (as are we all, apparently) being “threatened” and how these teachers are in “an especially vulnerable position because they lack any type of academic freedom or shared governance rights… they are a class without representation… [they have] precarious employment, which is spreading all over the world… [creating] professional insecurity and helps to feed the power of the growing management class.”

Whew. I am glad he got all of that off of his chest in the first paragraph. It is impossible to tell, from these multiple theses, that the point of his essay is to not use student evaluations to assess teacher performance.

I am sympathetic with his implication (or my inference), which rejects the consumerist mentality that has overwhelmed education in that last few decades, although I am more inclined to blame the faculty for being asleep at the switch, too readily giving up their responsibilities for governance, thereby letting the management class (including the lawyers) swoop ever so vulture-like into the void.

OK, OK. It is easy to get carried away when writing about these topics.

And I am always cautious about the claim of anyone lacking any type of academic freedom, because “academic freedom” has recently been overblown as a license to say or do anything without consequence. Indeed, if anything, academic discourse has been more restricted by internal policing than by external forces, it seems to me.

Samuels begins his essay with a percentage statistic. Did you notice that?

It has been common, for the last decade or so, for editorialists to at least imply that tenure track jobs have been lost and replaced by a growing class of non-tenure track faculty. The real picture, as you might suspect, is not so clear-cut.

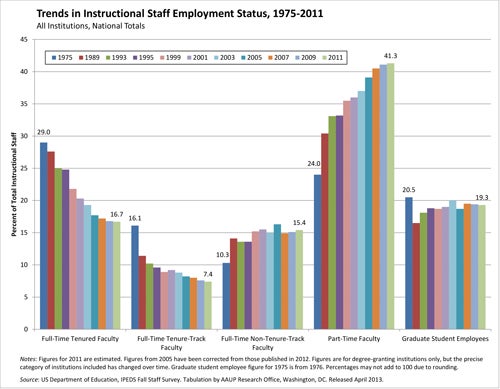

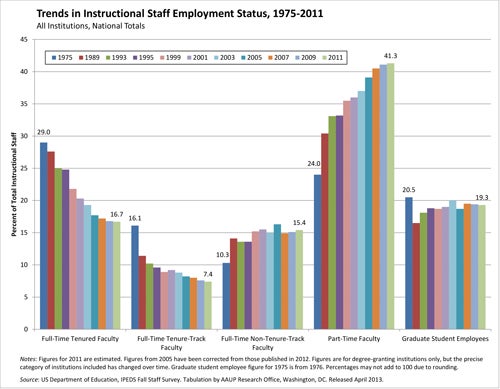

Samuels rightly links to the dramatic graphical data (above) from the AAUP (American Association of University Professors), 1975-2011, which records the steady decline of the percentage of full-time tenure and tenure-track faculty as changing from 45.1% to 24.1%, and the part-time faculty as rising from 24.0% to 41.3%. The “75%” in the AAUP numbers needs to be attenuated somewhat from the get-go, given that graduate student instructors (TAs) are included in the ranks of the “75%,” but that percentage is nearly constant over this time period (20.5% to 19.3%).

Samuels rightly links to the dramatic graphical data (above) from the AAUP (American Association of University Professors), 1975-2011, which records the steady decline of the percentage of full-time tenure and tenure-track faculty as changing from 45.1% to 24.1%, and the part-time faculty as rising from 24.0% to 41.3%. The “75%” in the AAUP numbers needs to be attenuated somewhat from the get-go, given that graduate student instructors (TAs) are included in the ranks of the “75%,” but that percentage is nearly constant over this time period (20.5% to 19.3%).

Diving a little more deeply, there are two things to keep in mind to understand the “75%” and the percent changes shown here.

First, the number of students in higher education over this time grew substantially, from 8.6M (1970) to 11.1M (1975) to 14.3M (1995) to 21.0M (2011). In 2011, there were almost a many students in 2-year programs (7.5M) as there were in all of higher education in 1970.

What increase in the instructional workforce will result when the population of students doubles, and who is going to handle this teaching demand?

Second, and interestingly enough, the total instructional staff, including graduate student instructors, grew by 136% (remarkably, perhaps, tracking the enrollment increase since 1970). The number of tenured faculty increased by 36% (227K to 308K individuals), and the number of tenure track faculty increased 8% (126K to 136K). The number of full-time non-tenure track faculty, which was lower in 1975 (81K) has grown to 284K, a 250% increase), and the number of part-time faculty, which was 188K in 1975, has grown to 761K (305% increase).

So we have one of those situations, again, where you get to tell the story you want to tell to make your point. Both of the following statements are equally correct.

From 1975-2011, in US higher education…

… the fraction of tenured/tenure track faculty members has reduced by 45%.

… the number of tenured/tenure track faculty members has increased by 26%.

Maybe it is too much to follow, but I would have been happier if people such as Samuels would give me a bit more to go on when they decide to make a point with numbers such as these.

Now that more than 75 percent of the instructors teaching in higher education in the United States do not have tenure…

From 1975-2011, the increase in instructional ranks (136%) is comparable with overall increase in student enrollment (100%) in US higher education. While the absolute number of tenured/tenure track faculty members has increased modestly (30%), the fraction of instructors who are not tenured (or tenure-able), including graduate students, has increased from 55% to 75%, representing an increase from 430,000 to 1,140,000 individuals in the workforce.

Listening to my former students who ended up with MD degrees, there are negotiations in the medical profession, especially in large settings, which sound remarkably the same as any blue-collar labor negotiations. How many days off? Which hours for work? And so on. These are even issues that are negotiated up front during the hiring process.

Listening to my former students who ended up with MD degrees, there are negotiations in the medical profession, especially in large settings, which sound remarkably the same as any blue-collar labor negotiations. How many days off? Which hours for work? And so on. These are even issues that are negotiated up front during the hiring process.

Mark Evanier works in the television and movie business. He tells this joke when he gives The Speech to some would-be creative artist.

Mark Evanier works in the television and movie business. He tells this joke when he gives The Speech to some would-be creative artist.

Previously…

Previously…  Samuels rightly links to the dramatic graphical data (above) from the AAUP (American Association of University Professors), 1975-2011, which records the steady decline of the percentage of full-time tenure and tenure-track faculty as changing from 45.1% to 24.1%, and the part-time faculty as rising from 24.0% to 41.3%. The “75%” in the AAUP numbers needs to be attenuated somewhat from the get-go, given that graduate student instructors (TAs) are included in the ranks of the “75%,” but that percentage is nearly constant over this time period (20.5% to 19.3%).

Samuels rightly links to the dramatic graphical data (above) from the AAUP (American Association of University Professors), 1975-2011, which records the steady decline of the percentage of full-time tenure and tenure-track faculty as changing from 45.1% to 24.1%, and the part-time faculty as rising from 24.0% to 41.3%. The “75%” in the AAUP numbers needs to be attenuated somewhat from the get-go, given that graduate student instructors (TAs) are included in the ranks of the “75%,” but that percentage is nearly constant over this time period (20.5% to 19.3%).