Ugly Object of the Month — May 2022

By Suzanne Davis, with Dr. Laura Motta

Welcome to springtime, Ugly Object fans! It’s for reals this time! It hasn’t snowed for at least a week, and after a million months of winter, that feels like a miracle.

You know what else is a miracle? Seeds. I’m getting ready to plant some in my garden now that the ground isn’t frozen. Every year when I stick them in the dirt, I feel like, “there is just no way this is going to work.” But then it does!

Because it’s that time of year—a time of minor miracles and new beginnings—our object this month is a sample of ancient coriander seeds.

My involvement with these seeds, which were excavated at Karanis, Egypt, is pretty limited. It consists mostly of making sure they don’t get damp or catch a fungus. But the Kelsey does have a real-life research expert in this area: archaeobotanist Dr. Laura Motta.

Dr. Motta’s research explores social complexity through food production and redistribution patterns, and much of her work focuses on the early phases of the world’s first cities. And yes, seeds help her do this! She agreed to sit down with me to answer a few seed-focused questions.

S.D.: Are these seeds for real? Were people at Karanis really eating cilantro and cooking with coriander 2,000 years ago?

L.M.: Yes! Coriander was very popular, and we know for sure that it was cultivated 2,000 to 3,000 years ago. But it’s also native to the Mediterranean region and to parts of Asia, so it would have been around even before it was cultivated. Coriander seeds have been found in large quantities in archaeological contexts much older than Karanis, such as King Tutankhamun’s tomb. The oldest known context is a Neolithic site about 7,000 years old. By Roman times, coriander was a very common cooking herb. One of the cool things about it from a culinary perspective is that the entire plant can be eaten, from the leaves—which, by the way, are called “cilantro” only in the United States—to the seeds.

S.D.: If I planted these seeds in my garden, would they grow?

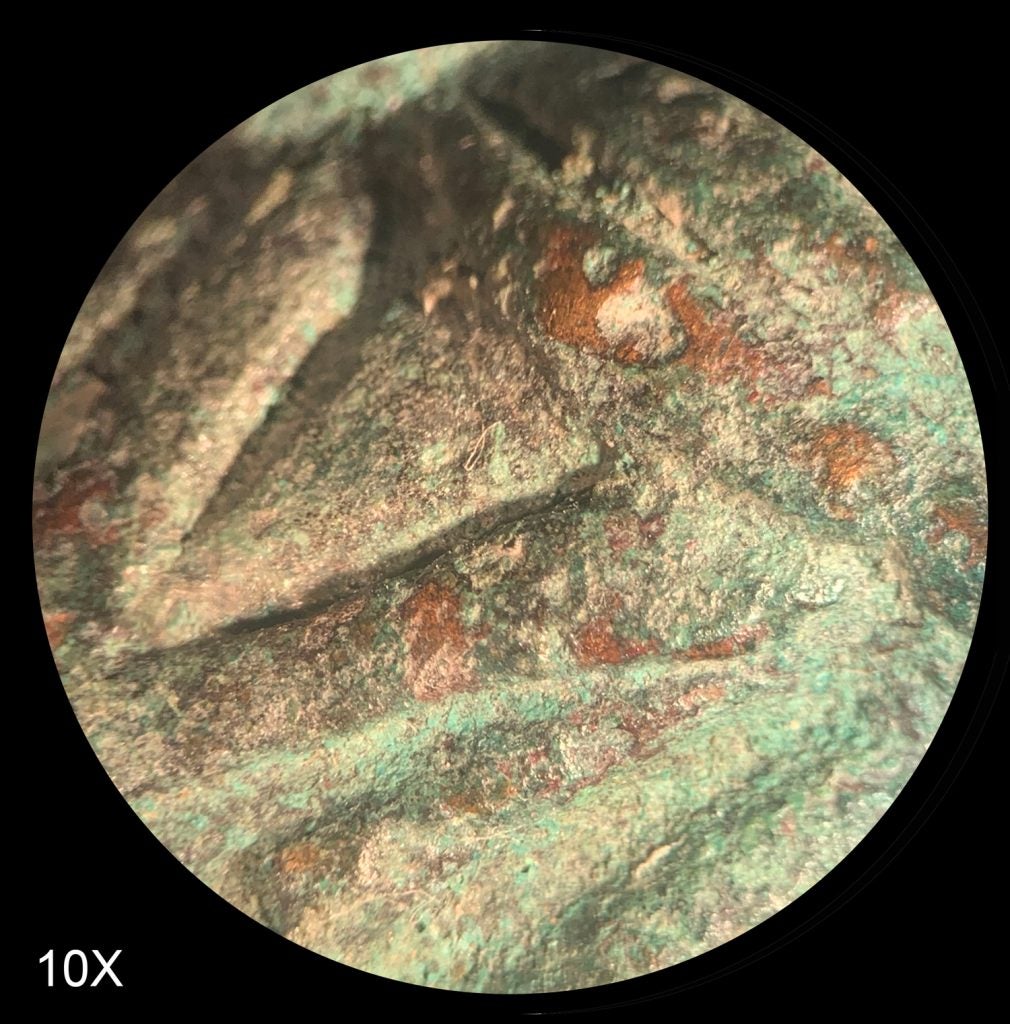

L.M.: They probably wouldn’t grow. Not only are these “seeds” very old now, they’re not actually seeds. Technically, what we call coriander “seeds” are the plant’s fruits. The real seed is inside the small capsule you see, like it is for similar plants such as caraway, fennel, and dill. So you’d really be planting very old, very dried fruit.

S.D.: That sounds pretty dubious! So what kinds of information can you learn from seeds, or dried fruits, that are this old?

L.M.: You can learn a lot. Most of what we have preserved in the archaeological record is not spices or herbs like coriander, it’s major crops like legumes and grains. Karanis is unique because the preservation is so good that you get both major crops and things like herbs. For archaeological research, the great thing about seeds of any type is that everyone has to eat. Unlike objects, which often tell you more about the elite people who could afford to amass wealth, seeds tell you about everyone. Seeds can tell you what people at all different levels of society were eating and what crops they were importing and exporting. At places like Karanis, they can even show you differences between what people have in their houses for their own consumption, and what they are officially recording and reporting in letters to Rome.

S.D.: What’s one important, specific thing you’ve learned by studying ancient seeds?

L.M.: One of my most amazing discoveries was four tiny millet seeds that I found when collecting flotation samples at a Middle Bronze Age site (ca. 1400 BCE) in the Carpathian Mountains. “Flotation” is a technique where you mix soil samples with water, and then strain out and examine any organic materials that float to the top. It’s a way of discovering tiny seeds and other archaeological plant remains that would normally be missed during excavation. The four tiny millet seeds I found in this flotation sample were extraordinary because the Carpathian Mountains are part of a big system of mountains that historically created a boundary between Europe and Asia. We know that millet was hugely popular in Asia and then, at a later point in time, also became popular in Europe. When I took that flotation sample I was expecting to see the same European crops I was used to at the site, like legumes, barley, and wheat. Instead, I found millet! Those four seeds are some of the earliest evidence of millet making its way into Europe. I was very excited when I found them!

S.D.: Would you agree that ancient seeds are extremely cool and worthy of a place in museum collections?

L.M.: Yes, of course! Museums show interesting things and help us see how the past is relevant, but with archaeological objects we can often still feel like they are very separate from us. A painted Greek vase is recognizable, yet most of us don’t have anything like it in our homes today. But seeds don’t change! They are so relatable. We still use them today in the same ways our ancestors did thousands of years ago. Seeds can tell us all kinds of interesting stories, and we should absolutely make more room for them in museums.