Brigit Pegeen Kelly was my mentor — a teacher and a friend who had a profound impact not just on my goals as a student but on who I would become, how I would view myself in relation to the world. She was the rare educator who could make you rethink what it was to learn. Her active listening was nearly alchemical; our conversations, at times, felt like a form of magic. Through sheer presence she could make the world new, more real, more full, and more resonant.

It was the kind of enriching that came just in time, not just in my life but as it was contained in a larger era. We talked about 9/11 right after it happened. We talked about the nightvision cameras that captured the first bombs dropping on Baghdad. We talked about the protests, the need for language and for silence. It was the new millennium, the new communication, the new politics, when the future seemed to be suddenly flattened and pressed into full view, when it seemed suddenly switched on. She is the reason I became a poet during this time, and she is one of the reasons why poetry has been so sustained in me through all these years, why it has remained necessary. These past weeks following her death have had me thinking so much about those years, when I could feel the inside of me getting burnished as though worked with invisible hands.

The very first workshop I ever had was with Brigit, and that very first day, when class was over, I knew that poetry was what I wanted to do. This isn’t hyperbole; within two weeks I’d added the major. Within a year I was waiting weekly, on Fridays, in front of her door, until she would come down the narrow, softly lit hallway to her extraordinary office — a large attic full of light and books — and let me in. Her pedagogy was so spacious, not like the skies or the sea, but like the air that can hang between two harmonized notes. It was almost ethical, the way you could feel her make room for you, how much she seemed to attend to the fact that you were of the world, like she was. We would talk over these heavy tanker desks — so practical — that ringed her in against an immense circular window that was like on oculus, clock face, and compass rose all rolled into one.

We would just talk: about the seasons, about our day-to-day experiences, about the larger, social world. We would talk about poetry, too. Craft was never a lesson but a way of orienting oneself. She would talk about my “ear” and its particular affinities. She would talk about the rhythms of the creative life as rhythms of nature and spirit, in which the ground could lay fallow, or be overgrown. Sometimes she would read something to me that she had just read. Sometimes we would take turns reading the same poem aloud. Her frank clarity about contemporary American poetry never led me to idolize poets as heroes, or to be tempted into scandalous tales of bad behavior — rather, she spoke of poets as people, always, in particular circumstances, with particular pursuits, and success always as something that was, in the end, personally measured. They were simple hours — unstructured but deeply structuring. In workshops or independent studies, she led with a similar, straightforward humanity — never did it feel like she knew something you didn’t; never did she assume anything about your capabilities or limitations: she was just there, guiding us toward a position of acute presence, to the poems as well as to each other.

James Merrill, in his introduction to To the Place of the Trumpets — Brigit’s first book — writes of her having the “wild, transforming eye of childhood.” Indeed we might see it, in “The Leaving,” as that which has watched us all our feverish night of work. “All night up the ladder and down, all night my hands / twisting fruit as if I were entering a thousand doors,” she writes:

And then out of its own goodness, out

of the far fields of the stars, the morning came,

and inside me was the stillness a bell possesses

just after it has been rung, before the metal

begins to long again for the clapper’s stroke.

The light came over the orchard.

The canals were silver and then were not,

and the pond was — I could see as I laid

the last peach in the water — full of fish and eyes.

Hers is the wildness of vision itself, vision as a form of union, of the Holy Spirit descended into a country aflame with wildflowers, a country written over with railroad tracks, stubble fields, and small towns, a place where by turns we love and are cruel, where we work and we fail, where angels walk out of the stained glass that has held them, or where life persists into death, like the singing goat’s head of “Song” or the “poplar that was felled / During the hurricane,” in “Three Cows and the Moon:” “For two years the tree bloomed / Where it lay, flat out on the ground. It didn’t / Know it was dead.”

Brigit’s poems are formalist in the best kind of way: as a materially textual revelation of the earth and the spirit in consort; of the prayers, stories, and songs by which we seek this consort; of “the realm of myth, archetype, fable, and metaphor,” as Merrill puts it, that lies beneath “the surface of personal experience.” But her poems don’t just recount this realm. She doesn’t simply read it from the old books. Hers is a constant vigilance, an onlooking so patient and steady that the world releases the secrets of its order. Look at her work in this brief section from “The Sparrows Gate,” which culminates in a feverish montage of a world harmonized by a single color:

If you lie on the grass in the dead of summer, and sleep, your body

heavier than stone, and wake to the sound of something

tapping and tapping like a sculptor’s tool on stone, and look up

from your dream to see a sparrow hurtling like a missile past

the stone woman’s left breast, right where the arm would have

been,

so that it seems for a moment as if the sparrow has destroyed

the arm or been carried off by it,

but it is hard to tell, everything is so bright, the woman’s body

blinding against the trees, shining like snow just before dusk, or

soiled magnolias, or buttermilk, or aged opals, or darkened ice,

or the full moon, or arms submerged almost to the shoulders

in a tub of water dark as tea or in the steeping pond.

If, if, if. I have admired so many different kinds of poetry since my years studying with Brigit. I have had other extraordinary mentors, editors, and poet friends. But the simple truth is that she taught me what to seek and how: poetry as vision, language as the unified field. As I write these brief words of mourning and remembrance, I can feel — almost with my hands, pressing against the resistance of my chest — the bell that she poured inside of me, a bell cast in my body as in the earth. So perhaps the best gift I can offer — for this poet who wrote so much about the sculptural arts, about ringing carillons rattling their vibrations to the fields below, about the golden quality of our touched existence — is one final bell: this scene, from Andrei Rublev — the exhausted satisfaction of a craft that has brought us beyond ourselves.

*

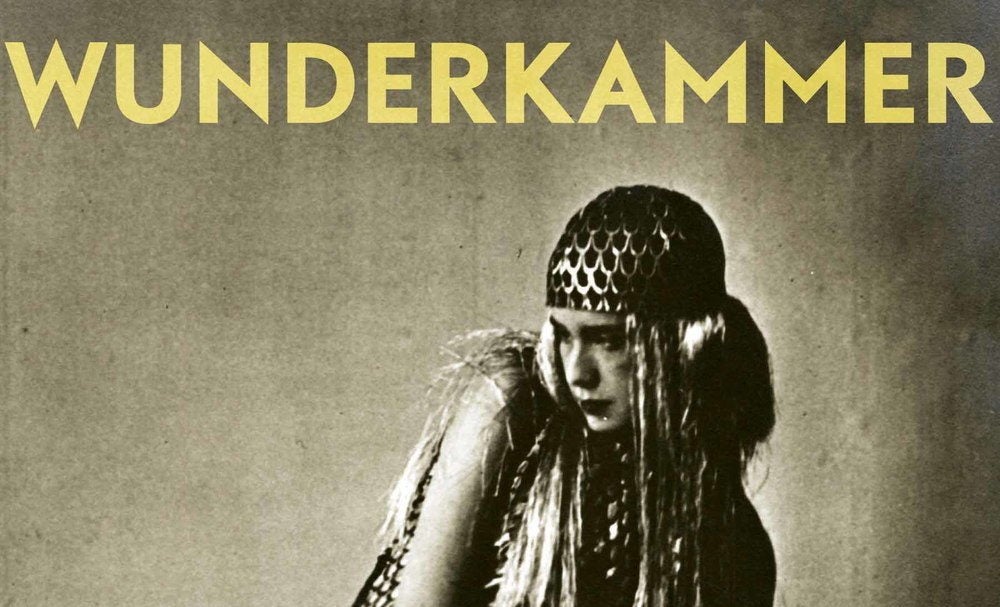

Photo courtesy of the Poetry Foundation.