In 1872, Susan B. Anthony cast a ballot in the presidential election in which Ulysses S. Grant would win his second term in office. Nearly half a century before women would actually get the right to vote in this country, this was of course an illegal act, and one for which Anthony was ultimately arrested and tried. She maintained her innocence, stating that it is “we, the people; not we, the white male citizens” whom the Constitution represented. Famously, she asked: “The only question left to be settled now is: Are women persons?”

Nearly one hundred years since women’s suffrage in the United States, still we’ve had no female president. We all know this, of course, but it was a surprise to me, certainly, the first time I learned it. In response to this dearth, I hit on the idea some time early in elementary school of becoming the first woman president. I recall eyeing Hillary Clinton warily back then, when she reached the White House as First Lady in 1993, her forty-five years to my eight giving her a significant temporal advantage in the race for first female as Commander in Chief. Consider what I have been up against: in 1993, Hillary Clinton was already age eligible to run, and in 2016, I still am not. (You have to have a minimum of thirty-five years on this planet under your belt to be president; you do not have to be a man, all prior evidence to the contrary.)

Fortunately, in the years in between, I’ve given up my presidential ambitions, so her presumed ascendency to the White House is not the crushing defeat it might have been for my elementary school self (though in so many ways this entire election has been a soul crushing ordeal). It was around the time we learned about Abraham Lincoln and the American Civil War that I abandoned my presidential aspirations. The possibility of assassination for taking a position to which others were vehemently adverse was a sad and frightening revelation, and somehow I’d already internalized the message that running for our highest office as a woman would be just such a position. I took to memorializing Lincoln instead, collecting pennies in his honor.

Thus concluded a short-lived campaign, begun with vigor some twenty-five years ago, but I think about those days so often now. Recalling Michelle Obama’s speech from the Democratic National Convention I dare to wonder: What could it mean, for young girls, and young boys, across this country, to grow up with a woman as president of the United States?

*

Recently, Rebecca Solnit published the third volume in her series of collaborative city atlases, this one dedicated to New York. In it, there is a revised subway map, called “City of Women,” in which each subway stop in the complex network of stations is re-named for a woman. (My subway stop, where the A, C, and 1 trains meet at 168th Street in Manhattan is named for Assata Shakur, a member of the Black Panther Party who lives in political exile in Cuba.) Solnit describes the idea in an essay that accompanies the map (and which was also published recently in the New Yorker), as a way to make visible and memorialize those women “routinely written out of history.” Solnit writes: “I can’t imagine how I might have conceived of myself and my possibilities if, in my formative years, I had moved through a city where most things were named after women and many or most of the monuments were of powerful, successful, honored women.”

In a discussion of the New York atlas, Non-Stop City, at the Institute for Public Knowledge at NYU in mid-October, Solnit mentioned a recent meeting with a group of students, in which she asked how they might have interacted with their lived environments differently if there had been more streets and subway stops named after female figures. She recounted that one young woman responded that it might be less likely for her to be sexually harassed on a street named after a woman.

When I related this account in my own classroom, one female student looked doubtful. She felt that was a rather optimistic take.

*

I think of my student’s remarks again as I read Ntozake Shange’s poem “with no immediate cause” from her collection nappy edges, preparing for that class:

every 3 minutes a woman is beaten

every 5 minutes a

woman is raped/ every ten minutes

a lil girl is molested

yet I rode the subway today

Women know these dangers, and yet we walk these streets, take the train, ride the bus, nevertheless. We ought not have to police our own movements, though there be immediate cause.

I don’t imagine that renaming streets is an answer alone to undoing a too long history of treating women as though they are not persons. Neither do I suppose that a female president will make it so that no woman’s pussy is ever grabbed without consent again, just as an African American president has not served to protect all black bodies. But I can only imagine it will be infinitely more helpful to the cause of gender equality to have a woman running the White House than yet another male, especially when our option with the Y chromosome is someone with a strong track record of treating women (not to mention members of the LGBTQ community, Muslims, Mexicans, African Americans, and on) badly.

After the first presidential debate this Fall (and the last I could bear to watch), I saw a woman who knows things be constantly cut off, belittled, and berated by a large, aggressive man on national television. I recognized the disrespect and disregard. I don’t presume to speak for any one else’s subjecthood but my own, but the moment stood for me as both universal and particular: it was behavior that might be widely recognizable to anyone who has been bullied, subjugated, or oppressed, and at the same time, intimately felt. I felt dirty for watching the spectacle; I did not know how I or she or we could ever be clean.

Afterwards, I read a poem by Khadijah Queen — “Any Other Name” — which a friend had shared on Facebook. I was grateful to find that poem that night. In this poem, there are these lines:

I cut off my hair because I wanted to

begin again with something on my body

no man has touched. I wanted to press

rewind. I still want the kind of purity that cures

men of acculturated entitlement. I want a little

silence when I walk down the street or get into the back

seat of a hired car in any city I travel to. Maybe

I have to marry myself.

*

I too cut off my hair some years ago. My goals were much the same. Still, they talked at me on the streets and in the subway, and now sometimes also taunted. They still touched, too, gaining pleasure in rubbing by bald head. The silence I also longed for was not obtained.

These slights are small, perhaps. But I have known the violence of men, and my body will not forget. Does not forgive — neither me nor no one else.

And so, yes, I take this miserable election personally, like so many other people I know. Day in and out we’ve been forced to endure — no matter where or how we get our news — the words of one major candidate, bragging about committing sexual assault and speaking hatefully of women and their bodies. Only one of the two major candidates on the ballot this time around would appear to answer Susan B. Anthony’s question with a “Yes.”

*

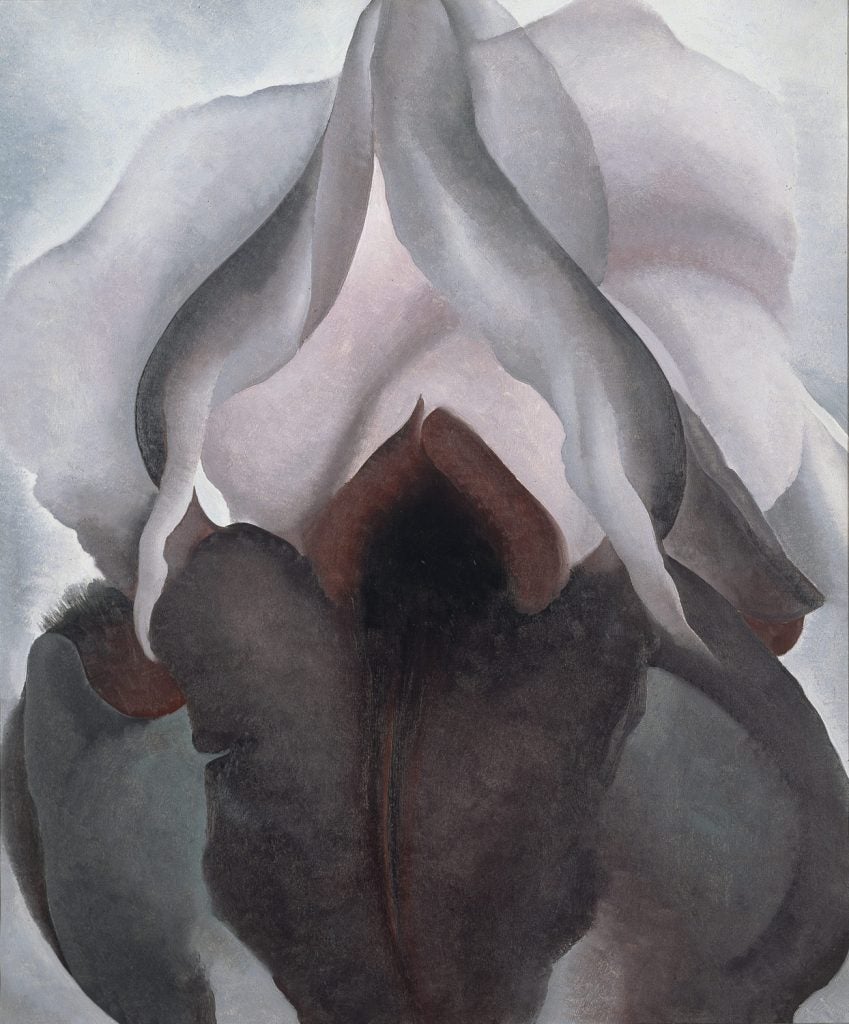

Lead image: Georgia O’Keeffe, “Black Iris” (1926). Inset image #1: Photo of the author taken by her mother. Inset image #2: Artwork by Audra Wolowiec, 2016.