“Go there—I know not where. Bring back—I know not what.”

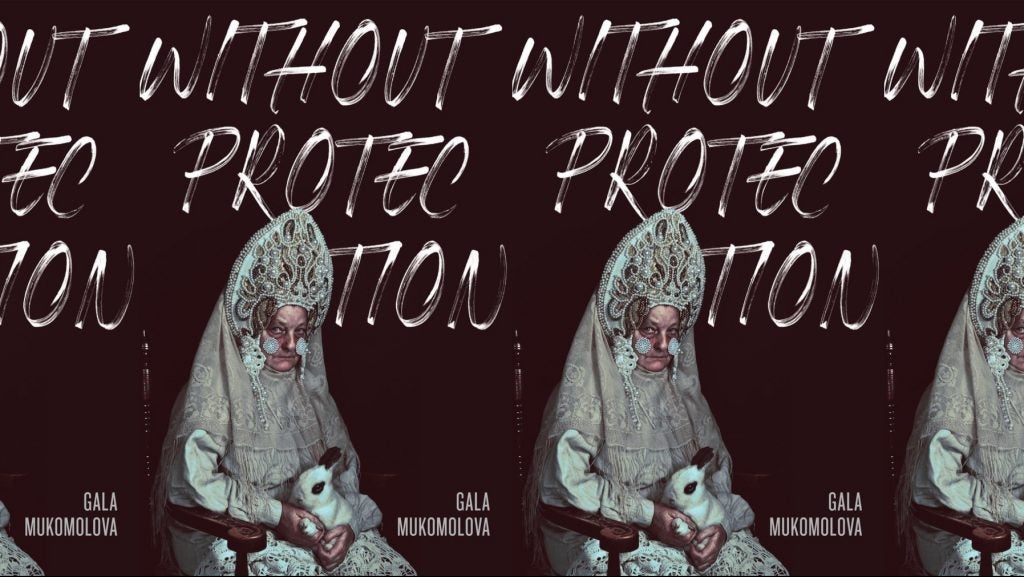

Translated from Russian, the epigraph to the poem, “The Heroine and the Witch” opens Without Protection, Gala Mukomolova’s debut collection that calls forth the Russian fairy tale of Vasilyssa and her journey to fight off Baba Yaga. Later in this poem, Vasilyssa tells Baba Yaga: “I come in the name of others and I come in my own name. I come for fire and for you. All of this and something else, something I’ve forgotten. Baba, I don’t know why I come.” In these lines lie the power of this collection’s unabashed exploration of unknowing and the unknown. It is with this unknowing that the narrator derives power and moves forward in her endeavors—not without fear, but in the face of fear.

Poems that follow Vasilyssa—as she questions and searches for love, works in Coney Island, and walks around Sheepshead Bay—divide and steer the collection. Mukomolova brings this story into the present day, and through this imaginative retelling, she injects myth and mysticism into the everyday, complicating its boundaries. Myths and fairy tales become not only just the stuff of the past, but also the stuff of the present and future.

You might know Mukomolova from her astrological writing (or what she calls “astro-inspired love letters”) in Nylon. Mukomolova states herself that she comes from a long line of witches; thus, it is no surprise that reading this collection feels similar to casting a spell. Operating between heaviness and flight, recurring images serve as the spell’s ingredients and help guide the reader through an imagistic language special to the speaker’s world. Mukomolova invites Craigslist Missed Connection ads, email correspondences, literary analysis, academic critique, TED talks, fairy tales, and much more to sit together, and by doing so, transforms this wide-ranging archive of experience into cherished relics.

The collection, as a whole, ambitiously walks towards the embodiment of a spectrum of emotions, and these emotions offer a threshold wherein the speaker must move through, just as Vasilyssa does upon meeting Baba Yaga—“Vasilyssa standing in threshold, through.” Something changes at each threshold, such as in “Twenty, sunburnt at Brooklyn Pride” in which the speaker reflects, “I took the boat. I let the boat take me.” The slight change of syntax expresses the speaker’s agency, while also suggesting the lack thereof—she acted due to circumstances beyond her control. It is these circumstances (puberty, trauma, immigration, loss) of which the speaker tries to make sense and move with, within, and through.

These experiences offer a lens with which to view the vulnerability of youth, who walk along the edge of desire and danger. There is a sense of knowing and unknowing that allows the events of each poem to go beyond normative interpretations of “right” and “wrong,” which Mukomolova emphasizes in “Tenderness”: “It is neither good nor bad / what happens to that girl.”

In reading this work, a part of me felt as if there was a loss of innocence, but I fight against the urge to think of this collection in such simple terms. Boundaries, it seems, don’t exist here. Exposure to sex and lust fills every corner, and with this, Mukomolova seems to suggest the non-existence of innocence and purity. Sometimes these moments are wistful, as with the poem “Copernicus”: “I slice German ham so precisely / I could kiss the woman who / bears witness.” Other times, these moments are violent and violating, such as in “There’s a young man, a teenager,” in which the speaker witnesses a man on the subway masturbating while watching her. And oftentimes, the reader sees the speaker as she sees herself—through others’ eyes. In one poem, she remembers, “He won’t fuck me because I’m not that kind of girl.” Gaze, expectation, and fantasy teach the narrator that her body belongs to others, not to herself.

Though these poems do not follow traditional forms, they have a presence and texture to them that feel very corporeal. While some poems constrain themselves with short, taut lines, other poems sprawl out like prose, as if a body enduring to reach the end of the page.

Though these poems do not follow traditional forms, they have a presence and texture to them that feel very corporeal. While some poems constrain themselves with short, taut lines, other poems have lines that sprawl out to the ends of the page. These different ways of being seem to speak to the narrator’s concerns with discipline and endurance and its affects on the body. In “Weekends with my mother,” the narrator recalls her experience working in a deli: “pull the broom toward yourself, [mother] said, grabbing it from me, sweat slicking insides of her arms. Acrid. Each stroke and sweep should be firm, have purpose.” Here, the long prose-like lines feel like an act of endurance.

Within these structures of discipline, we see a girl who longs for something more. In “Return,” she writes about disappointing her mother (“Years of rest and, she looks at me, of nothing to be proud”) and the physical abuse she faced (“I am covered in welts and empty pockets so large sobs escape me in the back room”). Empty pockets, being called “the girl with holes in her hands,” and comparing herself to “a girl with a hole in her throat”—these all give texture and weight to the speaker’s emotional emptiness, her void.

The wave always returns, and always returns a different wave.I was small. I built a self outside my self because a child needs shelter.

Not even you knew I was strange,

I ate the food my family ate, I answered to my name.

The poem’s ending couplets juxtapose sentences and fragments together, creating harmony through dissonance. The dissonance is further emphasized with the speaker’s experience of disembodiment—“I built a self outside of my self.” Desire runs strong, yet the speaker is unable to fulfill it.

The narrator’s discovery, then, is a return to the body and reclamation of it. As stated in the found poem “Received,” taken from an email sent to Mukomolova from a former girlfriend analyzing the character of Edna in The Awakening by Kate Chopin: “When we ignore the body, we become more easily victimized by it; for Edna, her body became an explosion of revelation that she didn’t know was attainable.” Poems like “So long my neck coils tight” attempt to let the body lead to revelation through the exploration of sex and power play and through a process of relearning and reclaiming one’s own body for pleasure.

Vulnerability and openness stands strong in this rich collection that sings of grief and longing. In the final poem, the speaker admits: “I was a warm live thing that wanted to be loved above all others.” Mukomolova writes with candor and honesty, but not without intention, as shown in the “Notes” section, which begins with an Adrienne Rich quote: “There are things I will not share with everyone.”

It might be easy for some to read Without Protection with a surface-level eye, harder to look at every carefully curated stanza and line to see something quieter and ineffable. Inviting the reader to stay within this collection’s world a while longer, Without Protection doesn’t have closure, nor does it want to. It exists and keeps on existing; it is a collection hard to pin down as it changes and grows with time, like a wave that always returns a different wave. This just means there is more to enjoy.

At the end of Mukomolova’s visit to the Helen Zell Writers’ Program, I had the pleasure of speaking to her one-on-one to ask about the sacred in poetry, her relationship to sound, pleasurable practices, and more.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

–

Jennifer Huang (JH): Yesterday [at your rountable Q&A], you talked about spirit and the way that it enters your work, and how poetry is a sacred space for you. Could you talk more about that?

Gala Mukomolova (GM): For me poetry is definitely sacred and in service of the sacred, even if what I’m writing about doesn’t look like prayer to anybody else. When I see the sacred in the work of others, I can feel it even if it’s not particularly religious or marked in some way. There are poets like Jericho Brown, whose poetry is queer and very spiritual. Or Alicia Ostriker, or Lucie Brock Broido. There’s also poetry that just feels like it’s in service to a kind of sacred understanding about why we’re here. For me, any kind of art—like making music, painting, and the kind of writing that you do because you have—is a service to something bigger. And I believe in a goddess; I also believe in many goddesses and that there is something that is not akin to a human form that is bigger than us. And I believe that those of us who create and make things into the world that underline the importance of being inside yourself, while also noting beauty—even if that beauty is a violent kind of beauty—are, in many ways, regarding the work of those [higher] beings.

JH: So you mentioned that when you’re reading, sometimes you can feel the spirit in the work. What does that personally feel like to you?

GM: Sometimes there can be a heat in the language, like a kind of movement. Or often when it’s very musical—not necessarily rhyming but work that is very interested in scansion or that is innately song-like. Sometimes when language is song-like and rhythmic, it’s because it’s coming from a core part of yourself that’s not interested in façade. It’s an inner layer. Like a hum, a vibrational hum in the throat. [She hums.] You can feel it right there, and there are poems that can feel like that hum.

The poems also often create a stillness, even if they’re moving very fast. You can sort of feel a bubble coming over you as if you and that page are the only thing present. You get really sucked in, even if the writer is totally outside your culture or interests or wheelhouse. And you think or feel something’s happening to me.

JH: You touched upon musicality, and I’m really interested in the ways you use sound and rhyme in Without Protection. The rhyme sometimes comes in a humorous way, and other times, it offers more of a slant rhyme. Could talk more about your relationship to sound and how that comes to you?

GM: I have a funny relationship to sound where I think for a lot of my life I’ve always been told I’m tone deaf when I sing. So there are many ways in which I will be in conversation with someone and say, I don’t get music. And I love music and love listening to it. But I do think I’ve internalized a lot of people’s reflections and experiences of me singing out loud onto my relationship with sound. And then I have this completely opposite experience, where I feel that I am very, very sensitive to sound and language. And I just think a part of it is pleasure. Sound is pleasurable.

The vibration of sound is so pleasurable, and it connects people. You can feel it living through not just yourself but through others, as well.

So if one were to distill that kind of pull or that desire, one can look at language and see pattern. Sounds also have hidden meanings. For example, a lot of K sounds can feel like staccato, an experience that’s like boom boom boom boom boom boom boom boom. Even if the actual thing that’s written isn’t like that, you get a sense that the writer is trying to do something where the reader experiences flashes or taps of something. Or when there are a lot of L sounds, it feels like smoothing. When you see a lot of L’s, you might get an image of somebody taking a piece of silk, pulling the ripples taut, then them happening again. We can go through the alphabet this way. There are signals with even just the letters.

And rhyme is relational. So rhyme allows you to think about the way words that are completely unrelated relate simply by the way they sound or the kind of endings they have. Or, maybe the fact that two words been holding hands through history. So this is corny, but rain and pain have probably been rhymed a million times. But that means rain and pain have just been walking together for centuries and have been doing so in many poems of the novice and of the master.

JH: And if you put them together you can call back to all those other times.

GM: Yeah, and also reunite them. And maybe that’s why sometimes it can feel quiet using them because they’re like, we’ve met before.

JH: You talked a little bit about pleasure and sound, so what’s been giving you pleasure nowadays? What do you find pleasurable?

GM: Well, an ordinary pleasure for me is feeling peaceful or calm enough when I wake up to allow myself to do the ritual things that make my day better. So I think that it’s a sustainable pleasure practice. Choosing small things you know will make you more peaceful or calm in the beginning of the day is a really intentional thing to do, and it can be hard to decide that you need that over a certain kind of proof of your productivity.

A really pleasurable morning for me is when I have so much time that I can wake up and I can put the coffee on. I have this CD player in my apartment, which wasn’t mine but made me find all of these old CD’s from my mother’s place. One of the CD’s I found was this Hare Krishna CD I was gifted on the street when I was a teenager by a Russian Hare Krishna. And this is a corny CD; it’s not cool. And it definitely has a distorted interest in drum machine sounds and a kind of alt-rock that was very popular in 2004. That being said, there are really peaceful songs in it, too. And there are lots of little pleasures in that CD for me.

So, I usually put on this CD, and then I shuffle my tarot cards for an exceptionally long time. I pull two cards, and then I go through this book that is really smart. It’s by a woman named Rachel Pollack, and I wish I could remember what it’s called. It really interrogates and gives the cards a lot of nuanced meaning, but not necessarily in a reinvented way. Next, I’ll often open up this leather-bound journal I have that was gifted to me by my ex. There’s pressure in writing in beautiful journals, as you might know, but what I’m doing is just writing down the cards that I’ve pulled and taking notes from that book. So it doesn’t feel like a lot of pressure because it’s not like I have to write something beautiful.

And usually just writing that down will take me about an hour. It’s slow. And then I’ll close the book and the CD will still be going. I might go back a few songs. And then I’ll do, maybe, five sun salutations because they make my legs feel good. And then I’m a really good person for the rest of the day. I’m all the way there, because I have connected with my spiritual self and I have connected it with my physical self.

I don’t look at my phone the whole time. Then, when I am engaging with an onslaught of media information or the hopelessness of the fact that we’re living in a country that’s unapologetically fascist at this point, I can at least integrate that information and hold it in a body that’s been collected and stilled. I think it’s much harder to hold that kind of painful information, which we are inundated with and implicated in, when you’re scattered and when you might not have a deep sense of self or core value.

JH: What advice do you have young queer writers?

GM: Maybe the young queers have to forgive me for this reference because I know that there’s going to be some push back on where it comes from, but it wouldn’t be right if I didn’t reference it—Jack Halberstam wrote this book called The Queer Art of Failure. It talks a lot about the inheritance of a kind of failure in this particular hetero-normative-capitalist world, where we [queer people] are not made to survive in and not set up to do well. A lot of us are raised to believe that success is marriage and children and, if not those things, then a job where you are seen as a respectable, productive, and professional human being. And then queerness is inherently a rejection of those forms, which is not to say rejection of all those things.

The young queer community might be inundated with a culture that says you can succeed by having a YouTube channel or you can make whatever you want. They might feel they don’t have the option of failure anymore, and that if they fail at these measures of success (that were never ours), then somehow it’s actually a personal failure. All around them they’re being told that they they’ve got everything so why should they complain, but we know that it’s still very dangerous to be queer. Yes, in other countries, but also in this one. There are many people who are incurring violence all the time. And when you know that kind of violence and when you are in a community with it, then you know it might be more dangerous to be out, it might be more dangerous to talk about your trans-ness, more dangerous to talk about the kinds of relationships you have. And that disjuncture of the actual lived experience, the fear, and the kind of hiding that many of us are trained into, plus a culture that’s currently telling the youth of today that the future is so free—that can really be a tough place to live.

So my advice would be to remember that it’s not your fucking fault, and that you still have the right to fail and you could do so really beautifully. And it could be more fun than succeeding.