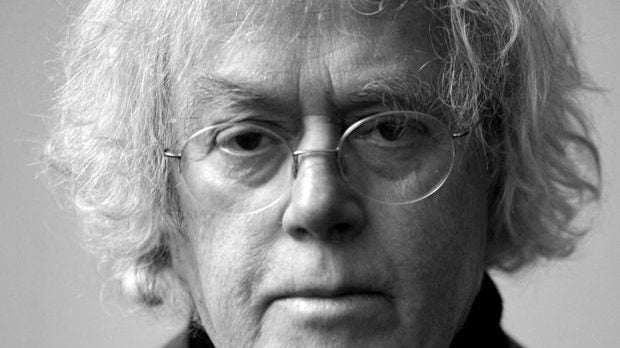

Dag Solstad (born 1941) is one of Norway’s most prominent and influential living writers. Since debuting in the 1960’s, his authorship has comprised well over a dozen novels, several of which are considered classics in contemporary Norwegian literature. His output can be divided into two very rough periods, the first of which runs from his debut up through the 1980s. In the 70s and 80s, Solstad was an active member of the Norwegian Maoist movement (known as the AKP-ml in Norway). As the novels from this period stem from his experiences with the communists, they typically have a very overt political element to them. Toward the end of the 80s, Solstad parted ways with the Maoists, and his novels from the 90s until the present day have moved away from political themes, instead dealing with his characters’ more personal, existential crises.

In Norway, Solstad’s early involvement with the Maoists is one of the most notorious and controversial sides to his authorship. However, the only novels by Solstad to appear in English are from the second period, from the 90s onward, where the early Maoist involvement is completely absent. I believe this gives an incomplete picture of his authorship, and part of my motivation for translating him is to help fill in the picture for English readers.

I reached out to Solstad by letter soon after arriving in Oslo near the end of May 2019. I wrote that I was an American translation student who’d received funding from my university to travel to Norway to research his novels. Specifically, I was interested in talking to him about Novel 1987, one of his mid-career novels that had yet to appear in English, and the one I had decided to translate for my thesis project.

I had begun studying Norwegian in 2005. I first settled in Bergen in 2007, and it was only a matter of time before this young man with more than a passing interest in literature would hear the name of Dag Solstad. My first encounter with Solstad was his Novel 11, Book 18, which I inched through in the original Norwegian with the help of Sverre Lyngstad’s English translation. I was living in a small hybel (flat) just beyond Bergen’s city center, and I was 26 years old—an age that Solstad himself described, in an interview, as the “decisive years.” The years in which one is “attentive, observant, (in which) everything is unformed, (and) you begin to orient yourself towards becoming a person.” It is a reader at this decisive age to whom Solstad claims all his books are addressed (Note 1).

After this initial encounter, I spent the next few years immersing myself in the lives of Solstad’s maladjusted protagonists: Novel 11, Book 18’s Bjørn Hansen, a tax official who hatches an unlikely scheme to defraud the Norwegian welfare system; Shyness and Dignity’s Elias Rukle, a high school teacher who ruins his life in a dramatic outburst after he can’t get his umbrella to work; and the protagonist of one novel who decides to join the Norwegian Maoist movement, whose life story is encapsulated in the unwieldy title: Teacher Pedersen’s Account of the Great Political Awakening that Has Haunted Our Country.

After ten years, I would be back in the States earning an MFA in Literary Translation at the U. of Iowa. A summer stipend enabled me to go back to Norway, where I managed to secure Solstad’s mailing address through a lucky mutual connection. A few weeks passed after I sent my letter with no word, so I called his phone number. Now, I’d seen YouTube videos of Solstad’s cantankerous treatment of interviewers he thinks are wasting his time, so I was unsure what to expect and trembling not a little. But I was met with a friendly voice on the other end telling me he’d received the letter and had just been too busy traveling and so on to reply just yet. He and his wife Therese Bjørneboe were at their summer home on the island of Veierland, south of Oslo, and if it wouldn’t be too much trouble taking the train, bus, and boat to get there, I was welcome to pay a visit.

On July 4th, my home country’s Independence Day, I found myself on a boat headed towards a little harbor, where the famous author’s shock of messy gray hair wasn’t hard to pick out from the small crowd assembled there.

It’s said that Walker Percy (author of 1961’s National Book Award-winning The Moviegoer) was so paralyzed by fear at the prospect of meeting the great William Faulkner that all he could do was sit in the car while his companion (Shelby Foote) had a lively conversation with Faulkner on the latter’s front porch. To meet one of your literary idols causes no small mixture of anticipation and nerves—that is inescapable. In my case, I think it helped that I was not unlike the person whom Solstad describes as his ideal reader—a little older, in my mid-thirties, to be sure, but nevertheless a translator in the making, in the process of staking a place for myself in the world.

In the translation excerpted here, we meet the protagonist of Novel 1987, a man who introduces himself to us by the single name, Fjord. As a fresh-faced journalist apprentice in Lillehammer in the early 1960s, the young Fjord embarks on his first reporting assignment, discovering an exotic new vegetable at the Lillehammer Open Market. As for my meeting with Solstad that July 4th, it lasted for several hours and covered many topics: from Solstad’s early student radicalism to his Proustian-influenced sentence style to his place in the European literary canon today. I was to have two more meetings with Solstad at his apartment in Oslo before the end of that summer, and the excerpts here are only a small fraction of the topics we covered.

Excerpt from Solstad’s Novel 1987

The next day it was raining. I got ready to go to work. Or was it to the office? I didn’t know how journalists phrased it and realized I’d better not say anything on the subject until I could gather what it was people said. This was no small problem, for I ran a serious risk of making an ass out of myself if I were to say, “I’m going to work,” thus referring to a journalist’s “work” in the same way you’d speak of “work” as a train conductor, a paper mill worker, or an electrician at Mesna Kraft, because this word, “work,” coming from the mouth of someone employed at a Labor newspaper, and especially if “work” wasn’t the preferred usage among journalists, might make it seem like I had scant respect for the paper’s readership, as if I believed sitting in a chair all day punching at a typewriter were the same thing as the physical toil that was most people’s lot, just as if I’d been employed at the Lillehammer Observer, where they probably called it “work” and could go on doing so for all I cared, if it so happened that “work” wasn’t the word you used when preparing to go to the newspaper that employed you, but if, on the other hand, I said: “I’m going to the office,” and that wasn’t the right term, why, I could already hear everyone’s laughter right behind me, and I blushed in my very tracks. He’s going to the office! Look, there he goes, that guy, who’s on his way to the office! Later, I found out that I was far from the only one who had difficulty expressing myself on that point, which is one of the most persistent and unsolvable problems in the profession. Hence the origin of what, for journalists, has come to be a popular tautology: A journalist is a journalist. Thereby, you go neither to work nor to the office. You go to the newspaper, plain and simple. I’m going to the newspaper. I’m at the newspaper if anyone asks for me. I’m on my way from the newspaper.

So, I went to the newspaper. My first workday. It was raining. First, I was sent to the post office to fetch the mail. Then they sat me down to practice at the typewriter, my lack of typing skills not at all uncommon among new recruits. After a couple of hours, I was given my first assignment. I was dispatched to the Lillehammer open market to write about the prices of fruits, vegetables, and eggs—in other words, how business was going at the open market today, August 2, 1961.

Wearing a rain suit, with pencil and notepad in my hand, I set out for the market to carry out my assignment. I went from booth to booth, diligently inquiring about the prices of the goods on offer, noting it all down conscientiously in my notepad, which was turning soggy from the pouring rain. I jotted down the price of redcurrant, of cabbage, making note of the steep discount on blackcurrant and on potatoes. The price of tomatoes was duly recorded, as well as that of carrots and cauliflower on this memorable day. The cost of eggs didn’t escape my attention, nor the fact that rutabaga remained a dependable, affordable choice for the Norwegian household. I also attempted to form an objective picture of the quality of the goods—but in secret, since I didn’t want to hurt the merchants’ feelings—and I observed that there were a lot of people at the market in spite of the rain. I wondered whether I ought to try and describe the delicate arrangements of fruits and vegetables in the booths, so that when Dagningen’s subscribers opened the newspaper, they would be struck not only by the aroma of carrots and redcurrants, of crisp cauliflower and juicy tomatoes but also the brilliant colors of Norwegian fruits and vegetables laid side by side in large booths. As I walked to and fro, diligently inquiring, taking in the atmosphere of buying and selling at an open market, I came upon something I’d never seen before.

At one of the booths, in the furthest left corner, lay a little display with a very strange-looking vegetable. A thick stalk branched out into several smaller stalks, topped by what looked like a bunch of little green knots. The whole thing reminded you of a small tree from the Mediterranean, and at the sight of these trees, tied into bunches on the furthest end of a vegetable booth at the Lillehammer open market, here at the gateway to Gudbrandsdalen, my curiosity was piqued. Miniature trees, with a Mediterranean charm, here, in all modesty, with a thick stalk for a trunk, smaller stalks for branches, forming a lovely crown of dark-green, knotted-up leaves. What on earth could this be! I immediately asked the man at the booth, and our proprietor—as I later styled him in my report—answered readily, and with no small touch of pride, that this was a completely new type of vegetable to Norway and was already quite popular in the nation’s capital, Oslo. He’d grown this himself and knew for a fact that he was the first person in Gudbrandsdalen ever to do so. Our proprietor went on to declare these miniature trees “highly recommended by nutritional experts and stay-at-home moms as an invaluable vegetable, full of essential nutrients,” as I put it in my article. Excitedly, I asked him how it tasted, and he replied that a taste test was unfortunately impossible right then and there because it had to be well cooked, but he could assure me that “it is exceptionally delicious, the taste comparable to a cross between cauliflower, asparagus, and green kale” (the latter two were completely unknown to me, I knew I’d never had asparagus before, and what was green kale? A kind of cabbage?). So what’s it called? What’s the name of this vegetable? I demanded. Brocoli, with a c, answered our proprietor.

Brimming over with enthusiasm, I made my way back to the editorial offices. I’d just discovered a completely new, funny-looking vegetable: Brocoli, with a c. I sat down to write my report. First, I had to write the dispatch by hand, then type the final draft with two fingers on the typewriter, before handing it to the assistant editor for approval and sending it to the press at Gjøvik via Telex. The writing of my report proved challenging. For one thing, I was burning to write about this novelty, brocoli, but on the other hand, a quarter of my notepad was covered in damp, half-faded notes about the price and quality of the goods for sale at the Lillehammer open market on August 2, 1961, which I didn’t have the heart to downplay in favor of the exotic newcomer with its hint of asparagus flavor. On top of that, it had been raining all day, and surely, I couldn’t omit that crucial fact from my article. How I struggled! Before I was even halfway done with my first draft, I was told it was much too long. My next drafts were also too long, I realized after making a few slight deletions. My third attempt corresponded to one full page in the August 3, 1961 edition of Dagningen, which even I could see would give a rather narrow impression of the day’s events in the vast expanse of our region. I was completely alone at the newspaper, the assistant editor having left for dinner, and the others having called it an evening, when, having cut the article down to an acceptable level, I could finally conclude my penciled manuscript and begin the lengthy work of typing it up.

“In spite of the gloomy rain, there was a large turnout at Lillehammer open market when we took a little walk over to see it yesterday. Business was lively, and it appeared as if both buyers and sellers were satisfied. The quality of the vegetables and berries was beyond reproach, and it looked to us like the prices were also largely acceptable.”

It was not without a twinge of disappointment that I had to resign myself to letting this stand as the colorful description I’d envisioned of the day at the market, to say nothing of the detailed lists of what everything cost. But in the end, I decided that I had to focus on the brocoli: first, a short intro that would sum up all of the great things I wanted to describe, and then: the new item!

“One of the people we spoke to has been coming to the market for more than 40 years and sells only his own products. This summer, he has been promoting a completely new vegetable that is already well-known and sought-after in Oslo. Brocoli is what it’s called, in appearance similar to a cross between cauliflower and an ordinary head of cabbage.” (I hadn’t complete faith in my own powers of description, so I asked my proprietor what he thought it looked like. “Cross between cauliflower and a head of cabbage, don’t you think?” was his reply, which I noted down in my damp notepad.) “It comes highly recommended by nutritional experts and stay-at-home moms as an invaluable vegetable, full of essential nutrients. It is exceptionally delicious, the taste comparable to a cross between cauliflower, asparagus, and green kale.”

Finally finished! In my elation, I topped it off with an inspired headline: “NEW, REMARKABLE VEGETABLE OBSERVED AT LILLEHAMMER OPEN MARKET YESTERDAY.” With that, I put the finishing touch on it. It had taken many, many hours, and evening had fallen by the time I could lean back, satisfied, in spite of everything, with what I’d accomplished. The editor-in-chief was already back for the evening shift and was sending material over the Telex when I laid my manuscript on his desk. He took it, skimmed, and said: “Headline’s no good, too long.” He wrote down a new one: “Business Booming Despite Rain.” With this new headline on a separate sheet of paper, he walked over to the Telex to send it to Gjøvik.

I waited until he was finished. This was my first article, and I was excited to see it in black and white on the Telex roll. I walked over to read it. There it was, with its new headline, along with a note to the printing press specifying the typeface for both the article and the headline. As I read through it, I saw that the editor-in-chief had made one small change. He had inserted a sub-heading within the article itself. At that time, it didn’t surprise me since I had no idea that Dagningen only rarely used sub-headings, and if they did, it was only in very long articles. This, on the other hand, was a short article, and a sub-heading was quite unusual. But sure enough, there was a sub-heading. About halfway through the manuscript, he’d taken the first word of a sentence and given it its own line before continuing the sentence on the next line. The word was:

“Brocoli”

Why had he done that? At that time, I thought nothing of it, since, as I said, I had no way of knowing that sub-headings were highly unusual in short articles, I only saw that there was a sub-heading, and it seemed entirely appropriate that it should be “Brocoli.” But as time has gone by, I’ve wondered about that. Why did the editor-in-chief take the unusual step of inserting a sub-heading in such a short article? You could, of course, say that he regarded the article as so insignificant that he found it necessary to shore it up with a sub-heading, so that maybe, just maybe someone might bother to read it through till the end, but honestly, I don’t put much stock in that explanation, since, even though my article was no masterpiece of journalism, it was no worse than a lot of other stuff that did just splendidly without any sub-heading in the pages of Dagningen, so I think the real reason must lie elsewhere. Had I struck a chord with him? Had he felt that scrapping my original headline—completely necessary on journalistic grounds—had been unjust, not on a professional, but a human level, where the thrill of having discovered a completely new variety of vegetable might be lost on the recipient of this news, whereupon he attempted to redeem it by abruptly separating, in the middle of the column and quite contrary to normal practice, the significant word, “Brocoli,” as a modest, but highly uncommon tribute to this remarkable event?

So that was that. I’d debuted as a journalist and, within a short time, fell into the ranks as Dagningen’s junior employee, always on the move to carry out the assignments I’d been given. I probably could’ve used a basic course in touch typing, but with two fingers, I managed to transfer my manuscripts directly from my head to the page, and fast enough that I avoided burdening the rest of the editorial office. I’d become a reporter, popping up and sitting ringside at many an event in the community life of Lillehammer and Gudbrandsdalen in 1961/1962, always with my notepad and pencil, often with my camera, every now and then with a photographer who’d been dispatched to accompany me in tow. I wouldn’t say that I became a familiar feature of the cityscape—truth be told, to most I remained unknown—but my ever-watchful, ever-vigilant presence could hardly have gone unnoticed by the numerous chairmen of temperance societies, language societies, local satellites, and youth wings of each political party, the Norwegian Red Cross, and the Association for the Blind, not to mention economic development officials, mayors, school inspectors, cinema managers, creamery supervisors, power plant managers, fire marshalls, hotel directors, chairmen and referees for Fremad F.C., the board of directors for the Lillehammer Speed Skating Association, the chairmen of the school boards from Lillehammer to Dombås, and the county governor’s advisor, such that, as I hastened down Lillehammer’s Storgata, or meandered my way up Gudbrandsdalen, any one of them might have exclaimed: There he is, the go-getter from Dagningen.

David M. Smith and Dag Solstad in Conversation

David M. Smith (DMS): I thought I might ask you a little about the translations of your novels that have been produced. Have you followed your overseas reception at all? How has that been?

Dag Solstad (DS): Yes, I’ve followed it. But I’m not so adept with languages that I’m able to comment upon it. I usually ask people who are more experts than me, is this a good translation or not? People who are good at German, English, French. As far as I’m aware, it seems like most of my books have had good translators, at least as far as the major languages are concerned.

DMS: Do you ever work with your translators?

DS: No, I leave that to…I was about to say my responsibilities go no further than the national border. What happens beyond it, I haven’t the background to…

DMS: Is it important to you to be translated into other languages?

DS: It’s fun, but first and foremost, I’m a Norwegian author. I define myself in relation to the Norwegian language, Norwegian society. That’s where I belong; that’s my life. Anything else, it’s interesting, but no more than that.

DMS: In your essay, “On the Novel” (1997), you say that you belong to “the Central European tradition of the novel in the 20th century.” Wouldn’t you say it’s important to have a place within this larger novelistic tradition in Europe?

DS: Certainly, it is. It’s more important for me to be a Norwegian with…I cannot imagine myself as a Norwegian who hasn’t read in translation the Central European novelistic tradition. Such a figure just wouldn’t be me.

DMS: You would say you’ve been influenced by, for example, Proust, Gombrowicz?

Solstad: Absolutely. Just as much as by the authors of my own country. I see you’ve in interest in (Tarjei) Vesaas, as do I. So I’ve definitely been influenced by him, but not in such a way that…

DMS: Stylistically, there are hardly any similarities between you and Vesaas!

DS: No, but he’s there as a part of my background and a very important part of it at that. Growing up, as a very young author, with the old man Tarjei Vesaas as a lodestar. I’ve written about him a few times, with great pleasure. Some of my best articles have been about Vesaas, and I’m very happy with those. I think I wrote a couple of articles about him. So the influence is more there as part of my heritage than anything you can trace directly in my writings. That’s what he means to me.

DMS: But Gombrowicz was a significant author for you as well, no?

DS: Yes, very important. He turned up for me at a very pivotal time. I was able to read Ferdydurke in a wonderful Danish translation. I’d probably have been influenced even by a bad translation, I think. I really enjoyed Kosmos, and I don’t think that was a very good translation.

DMS: Another influential author for you, especially when it comes to Novel 1987, is Proust, I’ve gathered. You were reading a lot of Proust when you composed it, so what would you say Proust’s influence was? Was it only at the sentence level, or was it something else?

DS: Yes, when I read Proust for the first time, it was in 1972 in Denmark, in Århus.

DMS: So it was a Danish translation?

DS: I came across the entire series in twelve volumes, I think, and I took this huge 12-volume set back with me from Denmark to Norway. I’d never done a thing like that before! And then why would I do such a thing? I’d read the first one to come out in Norwegian, the one called Swann in Love, but that was from a very small press, and there weren’t any more after that. So at that point [in ‘72], I thought: now’s my chance. Otherwise, why bother hauling these 12 heavy volumes, no? So 15 years would pass from then until Novel 1987, years in which I would read Proust every summer. I was totally fascinated by him that entire time. But it wasn’t as if there was anything in the way he wrote that I could somehow utilize in my writing, actually. I read him for pure enjoyment, and it’s good for authors to do that, to indulge.

But that changed when I started writing Novel 1987, when suddenly a lot of the way Proust writes started showing up in my work. With these long sentences, I began to think that—well, it may not be completely orthodox Proustianism, but I think that Proust is at his best when he writes solely about what fascinates him, regardless of whether it fascinates anyone else, he just keeps going on and on. So that’s what I’ll do.

DMS: Are there other foreign authors you’d say have been particularly important?

DS: In recent years, Thomas Mann. The Magic Mountain. But also Joseph and His Brothers. Those two.

DMS: Any American or English authors?

Solstad: Yes, I really like that guy with all the horses…

DMS: Who?

DS: That guy with all the horses. He shoots horses. What’s his name, McCormac?

DMS: Oh, Cormac McCarthy.

DS: Yes, him I quite liked. Him and Faulkner, whom I’ve long admired.

DMS: Some years ago, I was talking to a Norwegian about you and your authorship, and I remember what she said. She said, “I’m really not such a big fan of Solstad, since he’s always just so…political.” I remembered that because, if you think about those novels of yours that have been translated into English, it’s only those from the 90s onward. Novels were the political element much less than in those from the 70s and 80s. So, at least right now, it’s hard to imagine an English reader not liking Dag Solstad for being “too political.” So I wondered how important it is to you that this side of your authorship is better represented in translation?

DS: Yes, for me, that’s very central. My authorship is unthinkable without it. And even though I don’t write very much anymore about AKP-ml [the Norwegian Maoist movement], it’s always there in every line I write. So definitely, if the goal is to give a correct picture of my authorship in its entirety, then everything I’ve written before age 52 is missing. And I had a considerable body of work before turning 52. If I’d died at 52, I still would have been seen as a significant author, I would think, in Norway at least.

DMS: Right, and what’s interesting about the novels from the 70s and 80s, for instance, High School Teacher Pedersen’s Account of the Great Political Awakening That Has Haunted Our Country (1982), is that they are all about AKP-ml, whereas AKP-ml takes up only a small part of Novel 1987. And I’ve been thinking a lot about how to contextualize your body of work for English readers, i.e., how much information one would need to know about that time period, Norwegian society, and so on to understand what you were doing then.

DS: Well, if you think of Proust—I mean, I’m not terribly knowledgeable about the French upper-middle class circa 1890 that would give me some kind of special insight into Proust’s work. Those who are knowledgeable about such things probably have a special insight. But for me, even though I don’t know a lot about it, there is still a lot for me to gain in the way it is written. The way that Proust goes about doing things.

DMS: You have said previously that you were very angry when you wrote Arild Asnes 1970 [Solstad’s earliest political novel, in which the title character is a young author who joins the AKP-ml]. In that novel, we read: “Arild Asnes’s Norway was but a mere province of the worst superpower the world had ever seen: the United States.” And I was wondering how you view the United States now, 50 years later, with Trump, and so on…

DS: I can’t really say, though what I will say is that I have no memory of being especially angry when I wrote Arild Asnes 1970. It wasn’t until I read the novel again, when I recorded the audiobook version 10 or 15 years ago—it was then it struck me, my God, the rage that comes across on each page…And actually, I quite liked that sense of anger. And you might even say I kind of missed having that sense of rage.

DMS: I wonder if we can connect that to the opening of Novel 1987, in which Fjord pleads with his reader “…to try to listen, to take in this narrative, before judging me—Make an effort! Try, for once!” From this plea, it seems as if Fjord has committed some great crime or transgression, but he hasn’t, right?

DS: No, he hasn’t, and what he’s saying here, or rather, what I’m doing here is addressing a public that won’t share my point of view. Fjord hasn’t committed any crime, but what he has done is divorce himself from normal life in Norway, going in for revolution, that sort of thing.

DMS: So in that sense, he’s speaking to his own contemporary era?

DS: Yes, since this is in 1987, when I’d been with the AKP-ml for almost 20 years, right? So: listen to me! Try for once to listen to what I am saying! It is a very impassioned appeal. Even a little impertinent, I must say. Quite deliberately so.

DMS: Did you feel at that time that there were many who misunderstood you and your membership in the AKP-ml?

DS: Absolutely, yes.

DMS: How so?

DS: Well, in the sense that you were operating within a hostile arena. While also remaining in full solidarity with the notion of being Norwegian.

DMS: Solidarity, how?

DS: That is, solidarity with being Norwegian, while also being treated and perceived as an enemy of Norwegian society. And this was undoubtedly something that strengthened me from an artistic standpoint. To be heard, you have to be twice as good as everyone else.

DMS: Twice as good?

DS: Yes, if you haven’t got much else going for you.

DMS: And when you say everyone else, do you mean the other AKP-ml authors?

DS: No, I mean all other authors in Norway. The non-revolutionaries included.

DMS: But isn’t it one thing to ask for understanding if you’re Dag Solstad, the famous author, and another if you’re Fjord, this relatively anonymous figure?

DS: Sure it is, sure it is.

DMS: In a way, you’ve fictionalized your plea for understanding in this book.

DS: Yes, correct. But take, for example, the character Knut Pedersen [protagonist of High School Teacher Pedersen’s Account etc.]. One thing that Pedersen and I have in common is that we are both the children of social democracy.

DMS: The children of social democracy.

DS: Yes. And when we refused, when we broke with social democracy, in many ways it was an enormous personal break as well. For me, the break with social democracy was almost as sweeping as my break with religion. Though the break with social democracy was doubtlessly much more difficult.

DMS: One thing I’ve always found interesting is that the AKP-ml’s cultural influence was always much greater in Norway than its actual political power. Would you agree?

DS: Within literature, sure. Because, for one thing, all other authors had to take some kind of position on [what we were doing]. If you began writing about the working class, so did all the other authors that were out there. So the impact was there. Take Kjell Askilden, who’s turning 90 now, in a few weeks. God knows how much we talked about the great communist author Kjell Askildsen. We certainly could have, since he was the most important author we had at that time. If Askildsen hadn’t joined the AKP-ml through his son, then I don’t know how it would have been…when Kjell Askildsen joined, then almost anyone could, I almost said.

DMS: Come again?

DS: When Kjell Askildsen could join the AKP-ml, then I could, too.

DMS: Ah, because he was older than you?

DS: I think that kind of thing means a lot. But everyone talks about what a great author he is, but almost never that he was a communist?

DMS: Well, he hardly writes anything about the AKP-ml, does he?

DS: Not much. And this applies to other authors as well, like Per Petterson. Very few people talk about this nowadays, but I remember [Pettersen] as a young kid running around with the red flag at our summer retreats!

DMS: He was at the summer retreats the same time you were?

DS: Yes, I can remember thinking, my, these kids are really devoted to the cause!

Notes

- Quoted in the book Uskrevne memoarer (Unwritten Memoirs) by Alf van der Hagen, 2016.

- The book he’s thinking of, Requiem, actually came out in 1985.