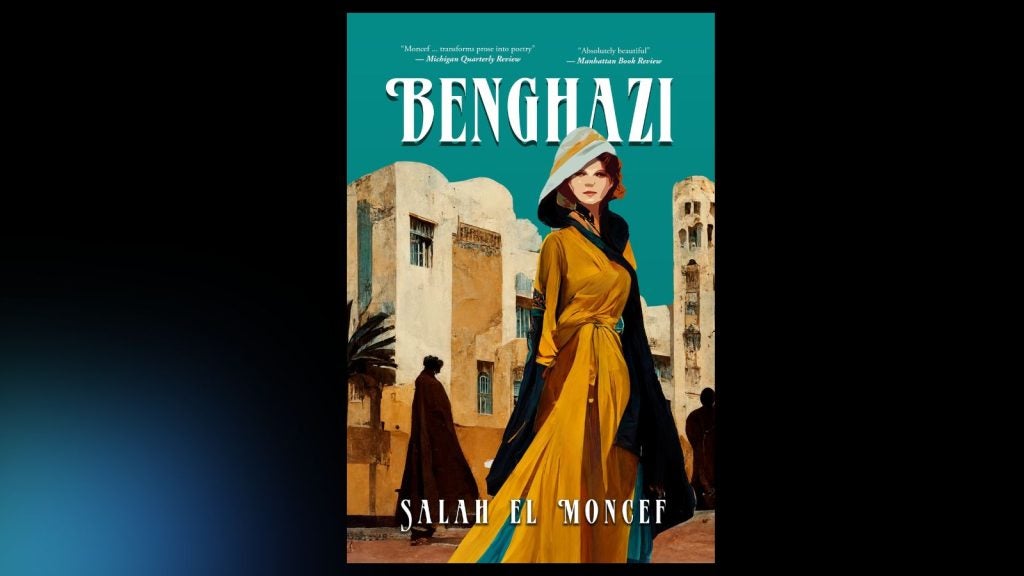

In her Introduction to The Offering (2015), Mari Ruti characterizes Salah el Moncef’s extraordinary novel as a “gripping detective story of murder, mayhem, and mental illness.” At the same time, she is quick to explain that while readers may be rendered “breathless” by this layered, at times frenetic, narrative, it is hardly the novel’s only attraction; the ambiguity and complexity of its protagonist Tariq Abbassi are, for example, equally and thoroughly engaging. The victim of a traumatic brain injury that has shattered his memory of a tragic accident and its life-altering consequences, Tariq hopes both to understand these consequences more clearly and to salve the unspeakable pain of the event, pain that frustrates his attempts to forge a new life in Paris and, later, Bordeaux that also feels “livable.” In this regard, as I underscored in the Los Angeles Review of Books (April 4, 2015), although the narrative of The Offering engages readers with the mysteries and heart-rending particulars of Tariq’s life (and death, as noted in the second paragraph of the book), his struggles also resonate with a much larger significance, in part by emblematizing the plight of diasporic subjects more generally who are never fully at home in their new country—or their old one. Similarly, in Ruti’s preface to Benghazi (2023)—most of which is set in this “cosmopolitan city perched on the Mediterranean” in the later 1930s and early 1940s as Benito Mussolini’s regime colonizes it—she identifies several of the novella’s more resonant historical implications, regarding the text as an “enormous enigmatic signifier… in the best sense of the term: an evocative, somewhat secretive piece of writing, that elicits the reader’s desire for more.”

She’s right on both scores. Because Benghazi delineates the colonial operations of mid-twentieth-century fascism as it also reveals their effects on the psychologies of its protagonist, Mariam Khaldoon, and her family, the reader does want more: more world history, more about her adolescence at the dawn of World War Two, more lush description from a writer whose virtuosity frequently transforms prose into poetry. Among the novella’s most expansive significations are el Moncef’s probing of the analogous feelings of human subjects dominated both by political autocrats and family patriarchs, his evocations of the increasingly perilous lives of Jews living in a city knuckling under the heavy thumbs of anti-Semitism and fascist pretension, the impacts of colonialism on education and civic life, and much more.

Although the provenances of Mariam’s interior life—and her over thirty-year avoidance of recording the fraught memories of her childhood—are less convoluted than those responsible for Tariq’s confusion and pain, they are just as crucial. And they are more straightforward. The Offering, as its foreword clarifies, conveys a story and, at the same time, is “the story of that story”: the text’s recovery from the “recesses of a near-defunct laptop” owned by its deceased author, its serial rejection by disinterested publishers, its delivery to an American editor who “patched it up as best she could,” its typesetting in England, and eventual printing. By contrast, in the opening scene of Benghazi, Mariam and her husband Basil, a professor at Indiana University in Bloomington, enjoy a sachertorte and coffee on a bright April morning in 1976. He leaves her briefly, returning with a bulbous envelope with the words “A GET WELL WISH” inscribed in gold letters on the outside. She discovers a gift and note inside, the opening sentences of which suggest both the appropriateness of his present—a Parker fountain pen—and a reminder of a specter from her past impeding her progress as a writer:

One way to deal with the sickness of the past would be to assume that some things that made us sick are now essential to our healing in the long run. Please finish your amazing story, and I will proudly translate the rest with as much delight as I translated Part One.

His alternatively encouraging and pleading tone, and the “GET WELL” inscription on the envelope, intimate that Mariam’s condition is both occasionally debilitating and ongoing. Will finishing her story promote healing? The story’s introduction ends with her resolve to do just that: “This is probably the best time to do it—finish what I started.” Now, over three decades later and half a world away from Benghazi, is the time to confront that “other spring” and “the roiling years that led up to it.”

Mariam’s project transports readers from 1970s America to Libya in 1942, then earlier to 1939 when her father suffered a fatal heart attack, and finally to 1937, the year Benito Mussolini came to Benghazi. His visit was a major event, and its planners worked on the pageantry of his arrival as if they were designing an operatic or theatrical production. A platform was erected in the city’s central piazza with flags and banners (including the Italian tricolore) flanking it on all sides. As Anna Burns notes in her Man Booker Award-winning novel Milkman (2018), flags, particularly national flags, were “invented” to be “instinctive and emotional—often pathologically, narcissistically emotional”—and such is the case on this afternoon in Benghazi. When Il Duce, attired in military regalia and astride a black Arabian stallion, entered the square, he was greeted by a “hurricane of cheers and applause”; the crowd’s “mad” excitement swelled further when he unsheathed the “Sword of Islam” and waved it triumphantly over his head. The strong man, the big man, had arrived with all the excess, pomp, and spectacularly choreographed circumstance the occasion demanded.

The day was made even more momentous for the Khaldoons when it was announced earlier that not only would Mussolini visit the Scuola Elementare e Media Giovanni Gentile where Mariam and her sister Zaynab were students, but that both sisters were chosen to greet him as representatives of the school. Zaynab was afforded the further honor of delivering the school’s official welcome. And she did so brilliantly. The sound of her “crystal-clear voice” and flawless Italian when reading the speech caused Mariam to swell with pride. Even their distinguished guest was impressed:

That achievement had apparently worked its way swiftly into the heart of the semi-clownish tyrant who looked so stiff and flushed, as if straitjacketed in his otherworldly uniform. He raised his eyebrows, popped his eyes wide, and gave my sister a deep nod of respectful admiration.

Mussolini’s nod of approval was accompanied by his enthusiastic “Brava, brava.” Yet, with an uncommon precocity, Mariam regards him as a “semi-clownish tyrant” in “otherworldly” uniform. Where does this acerbity, a tendency we have not recognized until this moment, originate? What factors account for Mariam’s cynicism? Was the dictator really just a low-comic buffoon, a precursor of today’s bloated autocrats strutting in a political farce?

As we learn later, not everyone in her family, one in which loyalty was valued more highly than any other virtue, shared in the refulgence. Not everyone, it seems, was delighted by the ostentation of the pageantry and the display of the Italian tricolore. In fact, long before this extraordinary afternoon, Zaynab and Mariam’s enrollment at the “Mussolini school” was, in some quarters of the family, quietly opposed. But surely this disagreement over schools or the sisters’ featured role in Il Duce’s welcome wasn’t responsible for Mariam’s unease? Even raising such a question recalls Mari Ruti’s quandary in her introduction to The Offering: “How am I to discuss this novel without giving away some of the plot elements that make it such a rewarding reading experience?” Her solution, reasonably enough, is to avoid the narrative and “stick to the story’s emotional and existential resonances,” and I will follow her lead. In a few instances, however, parsimony may be preferable to total avoidance, as unsatisfying as this miserly strategy might prove. So, I’ll say this much: Something else did happen as a result of this eventful day. And nearly forty years after the Italian fascist’s appearance in Benghazi, Mariam, buoyed by her husband’s encouragement and moved by his entreaty, decides to confront something she has not written about or, rather, not been able to write about. One last crumb of information: this “something,” slowly revealed as the story progresses, is as beautifully described as it is painfully, and subtly, recounted.

Even more beautiful are the many descriptions of Benghazi, the city forming, as Ruti notes, a character in itself portrayed through detailed landscapes and cityscapes. Happily, these passages exist in such abundance that selecting representative examples requires little effort and poses even less danger of giving away too much of the plot. Take, for example, Mariam’s view of Benghazi’s Market Square from her vantage point as a passenger on a bus stopped nearby:

. . .the full-sized orange trees that marked off the red-brick court of our outdoor market stood as radiant as ever in their wooden planter boxes. Their immaculate leaves were treated with leaf shine, as usual, and the navel oranges glowed like lanterns in the blue-green foliage. Beyond those neatly spaced planters, there was the customary motley scene of our market: dazzling arrays of roses and flowers in florists’ stands and the most amazing fruits and vegetables artfully arranged in the stalls and on the carts, their colors glistening, beckoning in the distance like the hypnotic hues of exotic porcelain novelties.

Stunning evocations of place and time abound in Benghazi: North African architecture and energetic civic life; familial interaction and intense affect; impeccable precision and bewildering ambiguity. So, while a reader’s enjoyment might originate, as it does in the case of The Offering, in the thrill of sifting through evidence and navigating a character’s memory, Benghazi allows us numerous opportunities to luxuriate in the beauty of the external world el Moncef creates.

In the end, this world is also transnational, and the lives of Salah el Moncef’s characters are thus “transnational” as well. However difficult and at times impossible, a transnational life is the only one Tariq Abbassi in The Offering wants to live, “in spite of the ravages of racist hatred and violence”—nightmares from which as an adult Mariam has been spared in a small American college town. Still, inevitably it seems, a transnational subject with a cosmopolitan worldview will necessarily have to contend with the goose step of nationalism until a more fully transnational world can supersede it. Until then, characters like Tariq and Mariam will carry with them scars from the worlds in which they live. One metaphor for these signs of past injury, manifested in very different ways in these characters’ lives, is what Paul Ricouer in his grand opus Memory, History, Forgetting (2004) calls an inscription. “Inscription” connotes a range of engravings, from the “get well wish” on the envelope Mariam receives from her husband to the faint etchings on a waxy substrate of memory that Freud compared to a “mystic writing pad.” Some inscriptions, like Mariam’s, also possess a profound temporal dimension. Ricouer deems these the “most problematic but the most significant” because they signal “the passive persistence of first impressions: an event has struck us, touched us, affected us, and the affective mark remains in our mind.” Salah el Moncef studies these marks in Benghazi and in much of his writing, and he does so in exquisite prose that readers will not be able to get enough of. They’ll want more.