A coming out party for underwear

In 2021 the New Yorker’s inside back cover—a full-page ad, hard to miss—shows a tall, hefty man of color, solidly planted on shapely legs, arms crossed over his chest, smiling, while wearing nothing more than Depend’s line of “absorbent underwear.” The bold word reaching across his entire chest reads CONFIDENT. No shying away from his virile bulge, as Saul Bellow called it, or a little solid middle-aged spread. Crossed arms read as manly honesty; it’s the pose of choice for CEOs and elite male artists.

A cultural critic like me had to think about the image, the text, the meanings, the context. To my eye, the tilt of the model’s head suggested the cat who swallowed the canary. The motto, below? “The only thing stronger than us, is you.” (“Us” is his underwear.) Thus, the ad overlooks, or just barely brushes, the reason “you” might need such superior strength. That reason is anti-disability bias, a force so powerfully ingrained in our culture that it will take the strength of many advertising dollars and of many bold innovators to eradicate it. Every part of the ad is fighting bias—politely, without mentioning it. At any rate, the word “stronger” slides in a flattering allusion to the power of both the wearer and the product.

Other recent New Yorker ads have shown white men of about the same years—sixty, perhaps—all performing the same comfortable, sexual, and subtly challenging attitude. Ads on TV for the same underwear show models with clothes on, active in ordinary approvable ways. In one, called “Hero,” the same actor, now dressed in an expensive suit, plays a father walking his daughter down the aisle. Some ads show younger women. An athlete—“a woman who is twenty reps deep and sprinting past every leak.” A woman dancing on her wedding day. An executive standing in her office (“overactive bladder”) surrounded by colleagues. Or on her knees looking at architectural drawings. Etcetera. One ad, showing a handsome woman of color in dreads, says “facing leaks takes strength, so [our company] acknowledges the strong women who trust its products.” “Trust” is another keyword.

Other companies have followed the lead. The Depend campaign from Kimberley-Clark started back in 2012 with a celebrity (who admitted elsewhere she didn’t wear the product) allegedly wearing the absorbent protection under her sleek designer dress. The big change since 2012 is the addition of men. The ads have appeared on Facebook, YouTube. Millions of viewers of all ages must have seen them.

Dignity is conferred, not innate

The campaign makes incontinence dignified. The intention must be profit and market share. The positivity of the tactic, however, distinguishes this campaign from others (for anti-aging creams and plastic surgery) that have leveraged existing fears of aging and disability. The dysfunction industries, as I call them, have the nerve to create additional fear of growing older in an ageist society. The pro-aging message of the Depend campaign is kinder and more subtle. These ads accept the reality of overactive bladders but otherwise dilute existing stereotypes of later life (“frail” and “weak”) with images of strength, activity, sociability, and independence—that is, normality. The outcome is unequivocally valuable, both socially and emotionally, in a society stratified by age, ability, and healthism.

Incontinence stereotypically links a physical issue to growing old. That is empirically untrue, or at least misleading. Millions of American adults—15 to 33 million, by some counts, not all “old”—are incontinent of urine, feces, or both. Urinary incontinence is more common than diabetes. The problem can arise from childbirth damage, prostate issues, or any number of other causes. The Centers for Disease Control’s 2014 study on prevalence concluded that over half of non-institutionalized women 65 and older and over one quarter of non-institutionalized men in the same age group reported some form of urinary leakage. Fecal incontinence that is chronic can have many causes. Incontinence can sometimes be treated—but, writes Dr. Louise Aronson in her renowned book Elderhood, it often goes unmentioned in physical exams, by either the patients or medical personnel.

These millions want their troublesome condition to be as invisible and ordinary as that of menstruating-age women during their periods who are wearing tampons or pads. Wearers want to avoid being seen as “disgusting.” A Ph.D. thesis about the stigma around incontinence, titled Unmentionable, declared that “both affected individuals and remedies for the condition—such as adult diapers—[are] subject to ridicule, embarrassment, status loss, discrimination, and even exile.” According to the author, Brendan Charles Gordon, who was writing in the late 1970s, retailers did not want to carry the product and AARP refused to carry an ad. We’ve come a long way. Not all the way, but a long way. Forty years later, incontinence is no longer unspeakable. It’s grinning in the New Yorker.

Baby incontinence—pee and poo—has not been treated as all that revolting in the US. Fathers used to be able to get out of diaper-changing, leaving the “dirty work” of smelling and washing the tush to women. But the invention of disposable baby diapers in the 1970s and the feminist movement helped weaken even that sturdy gender barrier.

The tactic of the underwear ads is to take a basic biological function associated with the nursery or the nursing home and put it squarely (but invisibly) into the daily lives of successful, active, attractive, non-disabled, and not-very-old people. Non-wearers are alerted to the possibility of absorbent underwear on anyone around them but are expected to stay calm and behave sociably. They don’t want to seem backward, or look embarrassed, at discovering the needs of others (or to put it more bluntly, the incontinence of others in their everyday “normal” world.) This includes people at the check-out registers at pharmacies and grocery stores. No more blushes at condoms, no more snide glances at big boxes of absorbent underwear.

Feeling disgust at feces, according to some heavy-weight theorists, was supposed to be one of humankind’s universal features. Yet it seems clear to me that culture determines what conditions evoke the feeling of repulsion and who is targeted for revulsion. Change is therefore possible.

Restoring Dignity

Older adults are often (but rather vaguely) said to “need dignity.” It’s not always clear, though, what dignity means, how it can be offended or jeopardized, and why it is necessary to affirm its importance so often. No vulnerable group can take their dignity for granted. People with disabilities, people of color, and menstruating women can guess why it is also important to maintain bodily dignity as we grow older.

One of the greatest fears related to aging, for many people, is having to be seen naked and needing to be cleaned by strangers. Consider a study in the United Kingdom that followed thirty-four people over seventy years of age, each of whom had health issues that necessitated varying levels of assistance. The aim of the project was “to identify factors perceived to promote or undermine a sense of dignity in older people in need of support and care,” and the analysis found that “[t]he prospect of being helped with personal care and of strangers seeing their naked bodies was unimaginable for some . . . ” What they said was “unimaginable” was in fact all too imaginable. For some, being intimately helped by their adult children rather than a paid stranger would probably be even more distressingly thinkable.

Probably the most consistent stereotype about nursing homes is that these facilities “don’t pass the smell test.” My friend, a retired philosophy professor, says that what he detects from afar is “the odor of rapacity.” He implies a terrible truth about bad nursing facilities, a truth known to every reformer. For-profit businesses own 70% of the facilities and lobby Congress with tempting cash; the federal government barely responds to their iniquities. State departments of health permit inadequate staffing of nurses and aides, and owners and operators underpay them. That means residents who need to be helped with incontinence won’t get assistance in time or won’t get the inciting cause treated properly.

The same Centers for Disease Control study reports that thirty-seven percent of shorter-term nursing home transients (usually in rehab after hospitalization) and 70.3% of longer-term residents reported not having complete control over their bladder. The lively new underwear ads can certainly make people in nursing homes who need pads or absorbent underpants feel more like the rest of us living in the noninstitutionalized world. And that by itself is good. Self-esteem matters. You have to enjoy anything that might inspire a resident to waltz in the hall with their roommate.

But what these ads cannot accomplish, alone, is the next important ethical goal in the campaign for bodily dignity: changing the stereotype that nursing-facility residents themselves are dirty and disgusting and showing that they are, in truth, often under-treated or neglected.

Teaching Younger People about Nursing Home Residents

“We leave childhood without knowing what youth is, we marry without knowing what it is to be married, and even when we enter old age, we don’t know what it is we’re heading for: the old are innocent children innocent of their old age. In that sense, man’s world is the planet of inexperience.”—Milan Kundera, The Art of the Novel

On this planet of inexperience, in a USA full of learned disgust and contempt of many kinds, what do we want younger people to learn about defecation and urination? First, that excretion is a function of all bodies, an action typically performed almost every day, probably in the morning, from very nearly the first day of life to the last. Anyone can suffer diarrhea or constipation, and these conditions can often be treated easily by taking a pill, following a different diet, or getting an enema. So much is universal, at least in nations with effective health care or public-health systems. Everything else is culture, in which dignity is dependent on geography and society, media representation, and attitudes to cultural purity, privacy, and class status.

Surely, we do not want young people to believe that excretion, just because it continues in later life, makes the body a sack of shit with a mind where “nobody’s home.” In his so-titled book (2004), Thomas E. Gass, who worked as an aide in a nursing facility, promises right away on page thirteen to “introduce” the reader to the people in his charge—26, too many for one aide in any circumstances—of whom seventeen are incontinent. His verbal portraits then tell us, again and again, in repulsive detail and with insolent humor, what these people’s bowel functions are like—and what some do with the feces. We learn about Skeeter, “conditioning his scalp with poop-mousse” and Ro, with her “reaming habit.” Over the course of his time at the facility, Gass tells readers, he came to treat some residents with sensitivity. He touched them lovingly; he kissed some. He opposed feeding them when they didn’t want to eat. Early on he even says, “I began to discover the residents as complete living individuals, fully co-equal humans, real people.”

His aim, I imagine, was to show how hard and unpleasant, as well as ill-remunerated, his labor as an aide was. The book was published by Cornell’s ILR (Industrial and Labor Relations) Press. Experts now say that a resident in a skilled nursing facility should get a minimum of 4.1 hours daily—actual work time by staff, split appropriately between Certified Nurse’s Aides and licensed nurses, adjusted for case mix—and with staff on floor, and calculated daily rather than a monthly or annual average, not fudged on weekends. That ratio means comfort, less pain, fewer pressure sores and infections, and lower mortality. Maybe even a little conversation.

Any state has the right to require this, as the fifty states license the facilities. No state does. There has never been a federally required minimum number of staffing hours per resident day. Gass got, he figured out, 27 minutes per person. He worked in a for-profit, understaffed, chiseling nursing home where, he tells us early on, the boss grossed $3 million a year and Gass himself earned a pitiful hourly wage as a self-described “butt-wiper.” He exposes a crime, which happens to be common. But that is no excuse for exposing his readers to so many residents’ nearly naked and soiled bodies.

The first time he chooses the more discreet term “bowel movement,” late in the book, it refers not to one of his charges, but to his daughter. This is family. So, he doesn’t describe the quantity or quality or color of her feces or whether she ever played with them; whether she ever has diarrhea or constipation. He, therefore, must suspect that he is crossing a line, ethically, when he describes the residents in their odorous and potentially humiliating moments. This transgression is all the more alarming coming from the very person employed to restore the residents’ bodies to clothed freshness.

Gass is like the blind man in the fable who gets the wrong end of the elephant. One blind investigator says the elephant is all nose. All tusk, says another. All huge stinking splashing behind, says Gass. But Gass’ fecal-centered “portraits” must also have helped sell the book. In The Anatomy of Disgust, William Ian Miller says that looking on, at scenes of degradation and disgust, has its appeal. He seems to be talking not about Freud’s babies, but about specific societies, especially the US. “The disgusting is an insistent feature of the lurid and the sensational, informed as these are by sex, violence, horror, and the violation of norms of modesty and decorum.”

Four Centuries of Asian Farmers

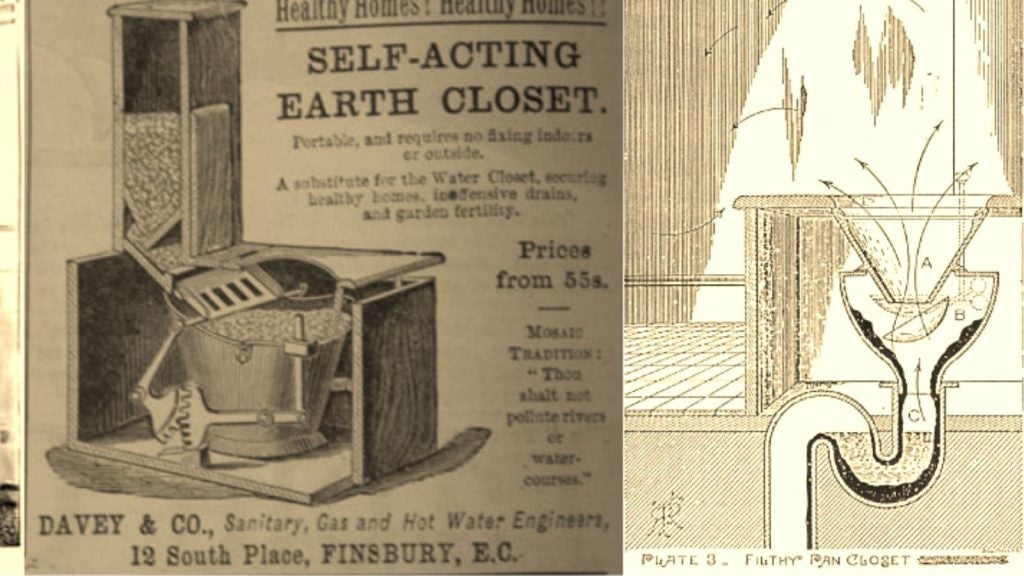

Mahatma Gandhi had a radically different view of human “night soil.” Counting on the human ability to learn new information and change harmful norms of behavior, he encouraged the low-income and low-status Indian citizens of the subcontinent to bury their waste for six months and then safely use the compost for fertilizer. According to scholars, he saw sanitation philosophically, linked to soma—the body; psyche—self-esteem; and polis—political liberty. Without regard for the Western heavy hitters who enjoyed writing about the “superior” emotion of disgust (Darwin, Nietzsche, Walter Benjamin), Gandhiji’s campaign sensibly made the products of excretion known as valuable. If a man can overthrow the British colonists, he can also undermine the cachet of their Western invention, the flush toilet. The prestigious W.C. wastes waste.

In the US, many parks have improved on the Water Closet. They provide clean “indoor outhouses,” which compost excretions without water. A Swedish invention, they are made by the company Clivus Multrum. The name, half-Latin, half-Swedish, means Inclined Mulch-Room. Abby Rockefeller sells the equipment in the US as an anti-pollution, no-water device, the answer to drought from New Mexico to Saudi Arabia. Abby told me recently how she got involved.

I had (still have) a vegetable garden in which I was putting all the manure of the various animals I had at the time—horses, pigs, sheep, chickens—and I couldn’t believe the attitude of EPA, that it wasn’t safe to use human manure in the growing of our food. I also had read Farmers of Forty Centuries [1911], which influenced me too. . . . While building [a small shed and toilet room] I read the article in Rodale’s Organic Farmer and Gardener’s Magazine about Rickardt Lindstrom’s compost toilet system in Sweden. I didn’t like to fly, so [I] asked a couple of friends who were going to Europe to go to Sweden and see if it “smelled”—the first thing I wanted to know. They said it absolutely didn’t smell. . . so I went to see for myself.

Gandhi may have known directly about Indian, Korean, and Chinese Farmers of Forty Centuries, even if he didn’t come across the persuasive 1911 book by F. H. King.

In the States, in 1972, Abby skipped from a passion for soil fertility and skepticism about EPA limitations to the latest Swedish technology. In 1979, we bought the uncomplicated system from her, after seeing and sniffing one in her home in Cambridge. It passed the smell test. Lacking a vegetable garden at our forest cabin, we use the odorless Clivus “tea” on herbaceous plants and evergreens. “Get your biomass together,” quips my husband. I have been known to declare, “Our shit don’t stink.”

Every good farmer who creates nitrogen from nutritionally rich cowpats and juice is part of the same campaign as the Asian farmers: to extract value from what was once just “waste.” Across the globe, one way or another, this formerly taboo subject can be discussed with intellectual objectivity, technological know-how, environmental pride, and an occasional smirk.

Public education

What training in caregiving Thomas Gass got, if any, isn’t mentioned. But in nursing homes the aides, like the nurses, should understand that people are rarely responsible if they suffer from incontinence. It can arise from many causes, some treatable. Chronic illnesses, accidents, and iatrogenic medical interventions, such as (the list comes from two surgeons) ulcerative proctitis and radiation proctitis, anal sphincter damage (i.e., from trauma, obstetrical injury, and surgery), decreased perception of rectal sensation (from, for example, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, and diabetes mellitus), overflow incontinence secondary to fecal retention and impaction, medication effects (i.e., laxatives, anticholinergics, antidepressants, and caffeine), and food intolerance (lactose, fructose, and sorbitol). When Gass describes Ro and her habit of “reaming,” a knowledgeable person may infer that she is attempting to deal with her serious constipation autonomously, without relying on an aide.

Visually representing a person as a naked body, without gaining their consent, is criminal. When “a nursing assistant photographed a resident’s genitals and sent the picture to a friend, who uploaded it to Facebook, the assistant was fired. Both were charged with invasion of privacy and conspiracy.” ProPublica published news of 47 appallingly inappropriate incidents over a mere three years, in which workers at nursing homes or assisted-living centers shared such photos or videos of residents on social media networks. The details come from government inspection reports, court cases, and media reports.

Verbal representation like Gass’s constitutes a violation of privacy, but it is not illegal. Are there other ways to describe the daily intimate tasks of aides like Gass? Of course. Tracy Kidder, the prize-winning author of Mountains Beyond Mountains, spent months visiting a decent non-profit long-term care facility in western Massachusetts. He got to know two residents, Lou and Joe, well enough to describe their habits of speech, their body language, their back-stories, and—the core of Old Friends—their increasing reliance on each other. He was close enough with these residents to quote them in times of humor and disappointment. Old Friends (1993) is a frank and lovable book.

Here, bowel movements are more delicately referred to, by the two roommates, as “B.M.s.” Joe and Lou prefer that the aides avoid even that polite formula, but just ask them daily, as they do their rounds, “Did you do it?” Nursing manuals discuss excretion in yet a different way. In some cases, diarrhea and constipation are dangerous concerns that require medical attention. They are never attributes of character. Kidder mentions aides providing pills or enemas. Kidder says that some people who can’t tolerate feces don’t last in the job beyond the period of probation.

Kidder’s way of describing the job of aides is as “accurate” as Gass’s. Realism is not measured by what details are included, but how they are presented, when, in what context, whether in the first pages of a book or once we know the people who are central to the story. Or whether such details are presented at all. Why was it necessary to tell us anything about Joe and Lou’s bowel movements? Institutionalization by itself tears the pants off the person. Do viewers who love Jane Fonda and Lily Tomlin want to know about Grace and Frankie’s bowel movements? It may be polite to ask in India, but not in the US. Cultures change, but not necessarily in the direction of other cultures.

At one point, as many as one-third of all Americans who died of COVID had been living in nursing facilities. Before vaccinations, in 2020, there were over 138,000 unnecessary deaths, of people who could have been better protected. More than ever, people had better be helped to understand what it might be like to live in one of those places. After all, we are each one accident, acute event, or chronic disability from spending time in one, or—depending on whether Congress and the states remain unwilling to expand home and community long-term care—ending our lives in one. Some students in gerontology, nursing, or medical programs are in training to work in nursing facilities. The rest of us are in long-term training to learn about the life course ahead.

There are ways to show people in what used to be called “adult diapers” with dignity: case in point, the ads of midlife models, POC and white, male and female, wearing padded underpants and going about their business. Comfortable. Dignified. In control. Seeing those ads without discomfort (theirs or ours) makes yet another part of the planet accessible to those of us who lack experience. We need to have our imaginations prodded to function better in relation to this form of otherness. In offices and in nursing homes, at weddings and sporting events, at our parents’ bedside and in a hospital ourselves, we should strive to perceive those who can’t make it to the toilet on their own as human, normal, self-respecting, deserving of privacy and dignity and prompt and courteous assistance.

If this blessing of imagination occurs to many of us, there would remain the political goal of getting all nursing-facilities to keep the people in their charge safe, clean, and feeling good about themselves. The challenge remains: we must get the responsible parties (the President, Congress, Health and Human Services, fifty governors and their departments of health, and the owners of 15,400 facilities) to commit to serious change—not to the institution’s image but its reality. To reach that outcome, I think we might need the magical twelve-year-old schoolgirl of Ali Smith’s novel, Spring.

In her school uniform, the girl boldly confronts the flabbergasted administrator of a UK immigrant-detention center and presses him hard about the squalid conditions he permits for his inmates. Ashamedly, he winds up having all the bathrooms and cells deep cleaned. One of the guards describes the process with amazement: “‘steam cleaners like at the car hand job places and they did all the pans and all the tiles and surrounds and then they mopped it all up afterwards, God, smells so much better in there, wait till you get on the wing . . .’ She went off down the corridor singing lines from oh what a beautiful morning using the corridor echo so the song went from one end to the other.”

So simple (Ali Smith knows), conferring dignity.

To read the rest of the issue, you can purchase the Winter 2023 issue here.