Joyce Carol Oates, the prolific American writer of great intellectual complexity, has built her intriguing works over the course of many decades. She has published over one hundred books, including novels, short-story collections, novellas, poetry, literary criticism, reviews, and essays.

Oates’s works have received the National Book Award, the F. Scott Fitzgerald Award, the PEN Malamud Award, a Bram St. Foker Award, a Heidemann Award, a Rosenthal Award a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Mademoiselle College Fiction Award, and Pushcart Prizes, an O. Henry special award.

In November, 2022, I had the pleasure of conducting an email interview with Joyce Carol Oates, who currently is the Roger S. Berlind Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Princeton University. In this interview, Oates discusses her work’s expansive, controversial, and distinctly American subjects.

Ying Chun: You are so thoughtful in the way you explore character in your writing, representing different kinds of female characters. I am interested to hear whether some of them might possess something in common with your own self-consciousness in some way.

Joyce Carol Oates: If you are asking whether fictional characters are imbued with their creators’ personalities and experiences—obviously, yes. But the art of fiction is the art of slant-narrative, and much in life is transmogrified by language. A novel like I’ll Take You There is a rarity, in which I am writing in a style very like my own, essay style, and the circumstances of the protagonist’s life (She is a freshman at Syracuse University, in approximately the time in which I had been there.) mirror my own. And some of the female characters of Babysitter are modeled to a degree on persons whom I once knew when I lived in Detroit. But more usually, my characters are almost entirely composed, created.

YC: Your characters, despite finding themselves in horrible situations, often lighten their lives with dark humor. It would be interesting to hear you say something about your female characters who possess a strong sense of agency and are active in shaping their own lives. Even if they have been frustrated, they seem to never be defeated. Might we call these characters ‘Oates heroines’?

JCO: Yes, this is true! I never write only about “victims” but rather about individuals who have survived difficult experiences and have become deeper and more self-reliant as a consequence—as in, for instance, My Life as a Rat and Marya: A Life. It is one of the abiding themes of my writing—speaking for those who cannot speak for themselves, bearing witness to the violence and injustice of the world.

YC: You also look at broader themes of female identity and experience. What was it that drew you to this?

JCO: Obviously, I am a woman who’d grown up in a pre-women’s liberation America, in the 1950s, then came of age in a new, revolutionary America in the 1960s. All this is mirrored in my fiction, as well as the imperiled state of such women’s freedoms in the 21st century, despite even the progress of #MeToo.

YC: It is interesting that Them and Babysitter are set in same city—Detroit. What is your emotional connection with the city?

JCO: Detroit is a fascinating city to me since it embodies much of American history: initially a “factory” town (Henry Ford, Father of American Automotive mass-production), then an astonishingly prosperous Boom Town (1950s, 1960s), but then, after the civic disturbance of July 1967 (sometimes called by journalists a “race riot”—but this is in itself a racist epithet), fallen into dereliction and disrepair, as the white, affluent population migrated to the suburbs, especially north of the city, and along the lake at Grosse Point. Thus, there came to be “two” Detroits—that of the affluent and that of the poor—which mirrors current-day America as well.

Of course, since I lived in Detroit as a young woman—young writer, young wife, young university instructor—the city is bound up with my own personal experiences when life came at me swiftly, with infinite fascination. Many of my stories are set in Detroit as well as novels like Them, Do With Me What You Will, and Expensive People. Zombie is set in Michigan and has a scene or two in inner-city Detroit, like the novella The Rise of Life on Earth—very specifically a Detroit-set fiction.

YC: It is precisely your sense of a special period in American history, particularly from the 1950s onwards, which is so distinctive of your work. In that sense, do you have any preference for 1950s and 1960s America in your novels?

JCO: No—I am interested in all historical periods, including the 19th century. (My next novel, titled Butcher, is set in the 1840s and 1850s and deals with medical abuse of the incarcerated, mentally ill, and enslaved persons.) My novel preceding Babysitter is set in the present time.

YC: Do you believe that the changes in character in your different works, chronologically speaking, go along with your self-growth or changes in your life?

JCO: This may be true, but I did begin by writing about persons older than myself in my early books. By the time of Expensive People, I was writing about a young teenager, but my first book, By the North Gate, has many stories of adults much more mature than I was at the time. I came from a close-knit family and had many relatives who impressed themselves upon me at an early age.

YC: I am also wondering if you could say something about the visual elements—including photos or family photos—in your writing. Your stories and novels have a striking cinematic quality. In Childwold; Because It Is Bitter, and Because It Is My Heart; We Were the Mulvaney; and The Gravedigger’s Daughter, we find many photos and other images. How and why did you choose these photos and images?

JCO: I have a strong visual imagination. I love to envision a setting and describe it. I would place myself solidly in the tradition of Thomas Hardy, D.H. Lawrence, Stephen Crane, William Faulkner—a fascination with physical settings, landscape. I am also akin to John Updike who loved to describe natural things—trees, clouds, and also people (whom John Updike considered part of nature). Much of the pleasure of writing Breathe was describing the sublunar landscape of the Southwest that seems “haunted” to the narrator with the ghost of her lost husband.

YC: Another important feature of your work is its versatility and the way your novels cross different classes of America. Do you find that different class backgrounds shape different characters, in the sense that you create characters from different social classes and explore how their backgrounds and experiences shape their lives?

JCO: America can be understood as a nation of classes, in conflict with one another. The tragedy of the 21st century is that so many American citizens, disenfranchised by poverty and a lack of education, especially regarding the new electronic technology, have fallen far behind the progress of the affluent; this helps to account for the smoldering rage of the “populists”—who vote for rightwing politicians, rather than politicians who would actually address their problems. This is not new in U.S. politics: “low-information” citizens voting against their own self-interest. Most American writers—Theodore Dreiser, Stephen Crane, Faulkner, Hemingway—deal with these issues, in very different ways.

YC: Do you find yourself deciding to work on specific mother-daughter relationships and struggles they encounter dealing with one another? Like in Blonde and Because it is Bitter, and Because it is My Heart: Norma Jean and her mother, Iris and her mother Persia?

JCO: The story of Norma Jeane Baker was very much a story of a motherless daughter, also seeking a father, in a quest to forge an identity. But there are many works of my fiction that do not deal with this particular theme, as in the recent novel Breathe. In Night. Sleep. Death. The Stars. the mother is a truly loving, generous figure for whom her adult children feel not only love but a powerful attachment—it is almost hard for them to grow up, marry, move away, become “adults.”

YC: What is the relation between the individual’s self-growth and the American Dream in your novels?

JCO: Probably Them is the novel that most addresses itself to the promises and illusions of the “American Dream.” In My Sister, My Love, the American dream has morphed into an obsession with becoming famous—a fatal obsession.

YC: Apart from its influence on your writing, I am interested to hear what you think of our visual and material (and immaterial) global media culture today. How have these new technologies affected and/or changed your own life?

JCO: The new media have not altered my life much at all. I continue to write and take notes in long-hand, on sheets of paper, and only to turn to the word-processor at a later stage. I am not much interested in video games, using my iPhone very often, and I no longer have an iPad or Kindle. (I prefer the three-dimensional object of the Book! Here we have striking paper covers, special end-papers, pages. There is much to be said of the book as an aesthetic object that cannot be replicated online.)

YC: I was wondering how you use social media as an author? What do you think the implications are of social media on your writing and creative process?

JCO: I don’t think of social media as integral to my life or my work. I find Twitter refreshing and engaging, in terms of those whose accounts I follow. It has been an excellent medium for sharing enthusiasms—recommending books, films, art, TV series—but also at times reacting to political outrages—a virtual community that replicates some of the advantages and disadvantages of a real community. But it has no connection to my writing, and indeed, at the time of this questionnaire, it looks as if Twitter may be evolving in a right-wing direction, so that many of us will probably detach ourselves from it.

My primary interest has always been literature—both to read and to write. That will continue!

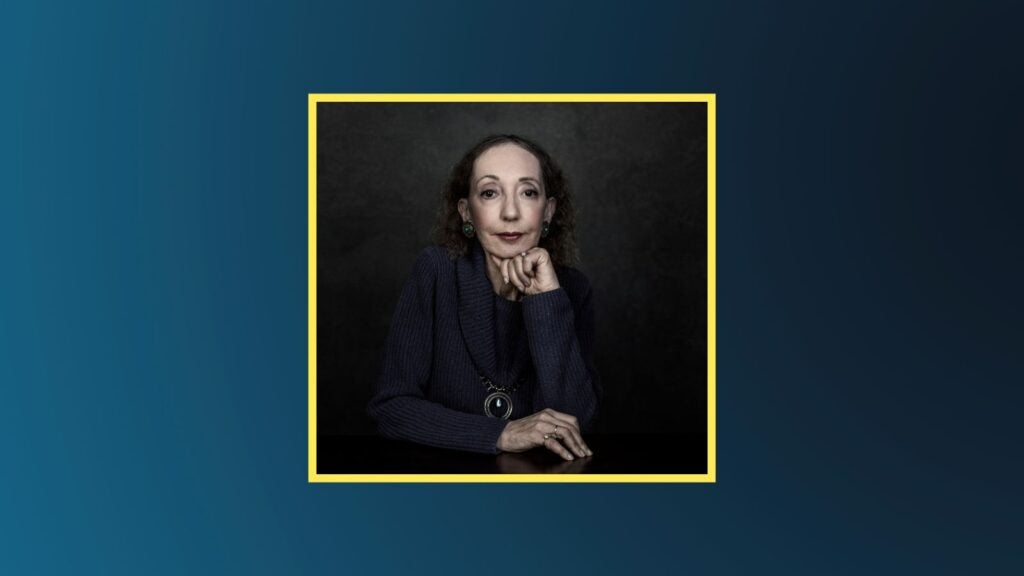

Editor’s Note: The author photo at the top of the page was taken by Dustin Cohen.