(Not) Content Not Curated

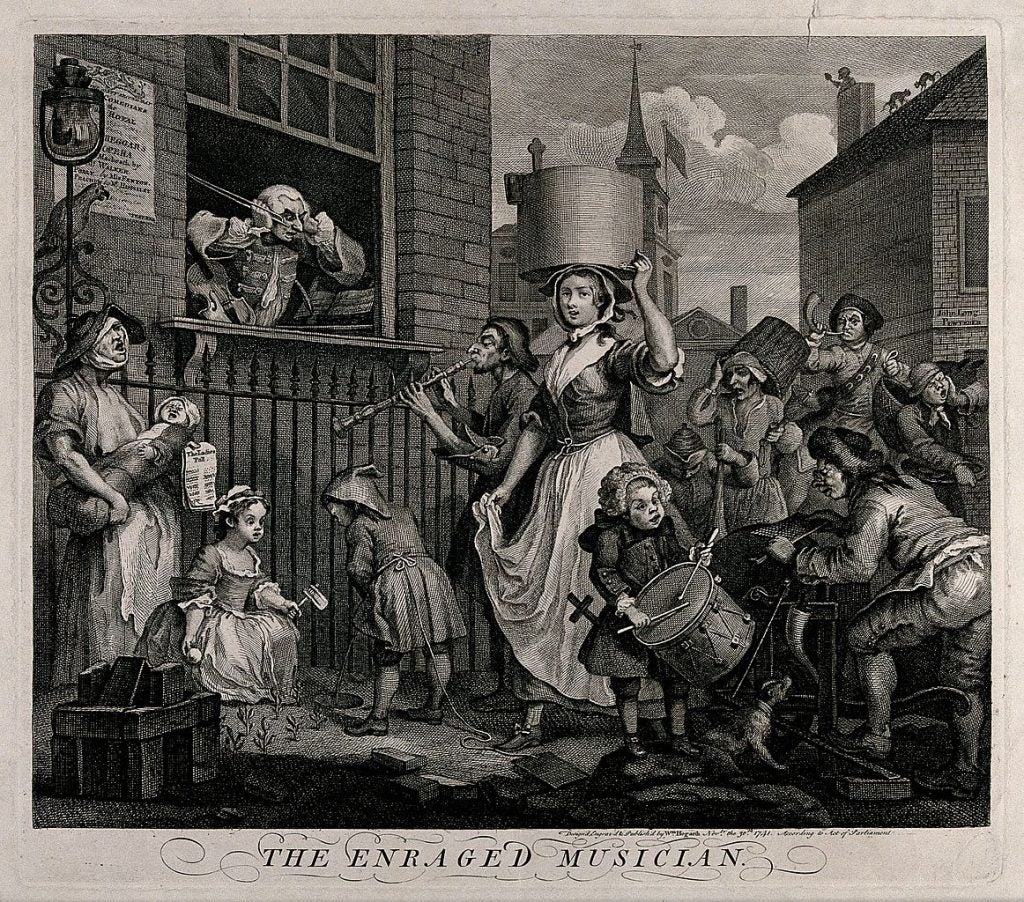

On being introduced to new art—ahem, content—via a short story about street hip-hop and crate digging, among other things . Before I knew it, I was surrounded. They were all around me, pressing closer and closer, and their eyes were piercing. Every time I turned my head, it seemed I was making eye contact with […]

(Not) Content Not Curated Read More »

On being introduced to new art—ahem, content—via a short story about street hip-hop and crate digging, among other things . Before I knew it, I was surrounded. They were all around me, pressing closer and closer, and their eyes were piercing. Every time I turned my head, it seemed I was making eye contact with