In my experience, one can describe what goes on in a classroom at three different levels:

The task completion model: the instructor lays out a series of requirements for students to complete, and students are graded on how well they execute the work. At first glance, this covers a large chunk of what goes on in a class: quizzes, papers, presentations, etc. But if this were the only thing going on, then it wouldn’t really matter what those tasks consist of. We could run an obstacle course every day, or have a bake-off, or compete in a trivia contest, if all we cared about was creating a venue for grading people. There would be no connection at all between the assigned tasks and any particular subject area or skill set. Task completion, on its own, is quite meaningless. It requires something with more substance, like…

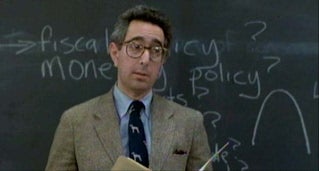

The task completion model: the instructor lays out a series of requirements for students to complete, and students are graded on how well they execute the work. At first glance, this covers a large chunk of what goes on in a class: quizzes, papers, presentations, etc. But if this were the only thing going on, then it wouldn’t really matter what those tasks consist of. We could run an obstacle course every day, or have a bake-off, or compete in a trivia contest, if all we cared about was creating a venue for grading people. There would be no connection at all between the assigned tasks and any particular subject area or skill set. Task completion, on its own, is quite meaningless. It requires something with more substance, like… The knowledge acquisition model: the instructor shares knowledge, and students are graded on how well they grasp that knowledge. From this worldview, the obstacle course isn’t just some arbitrary exercise, it is a means to an end, a way to give students command of some set of course material. The material might be factual–the meaning of certain terms, for example–or it might be skills related–how to perform a certain kind of analysis. But there is a problem with this approach, too. A class that is solely about knowledge acquisition is only valuable to the extent that the student retains and values that knowledge in the future. In the real world, of course, we forget all sorts of factual material we’ve learned, and we lose proficiency in skills that we don’t make regular use of. So if a class is only about acquiring knowledge in a given subject area, there is an excellent chance that it will prove to have been a waste of everyone’s time and money months or years down the line. The class must also include something more universal, like…

The knowledge acquisition model: the instructor shares knowledge, and students are graded on how well they grasp that knowledge. From this worldview, the obstacle course isn’t just some arbitrary exercise, it is a means to an end, a way to give students command of some set of course material. The material might be factual–the meaning of certain terms, for example–or it might be skills related–how to perform a certain kind of analysis. But there is a problem with this approach, too. A class that is solely about knowledge acquisition is only valuable to the extent that the student retains and values that knowledge in the future. In the real world, of course, we forget all sorts of factual material we’ve learned, and we lose proficiency in skills that we don’t make regular use of. So if a class is only about acquiring knowledge in a given subject area, there is an excellent chance that it will prove to have been a waste of everyone’s time and money months or years down the line. The class must also include something more universal, like… The critical thinking model: the instructor demands from students, and students build their capacity for, original, inquisitive, creative, synthetic thought and expression. Under this approach, the student is doing more than jumping through hoops in order to get a grade, and is doing more than downloading information and task instructions. Students are actually creating their own knowledge. They are writing essays that apply general concepts to their own experiences and interests; they are doing original research; they are questioning their own assumptions and those of their colleagues, the writers they are assigned to read, and their instructor. In doing all this, students are developing the habits and the experience to be able to create knowledge for themselves long after they’ve left the classroom, no matter what the subject area.

The critical thinking model: the instructor demands from students, and students build their capacity for, original, inquisitive, creative, synthetic thought and expression. Under this approach, the student is doing more than jumping through hoops in order to get a grade, and is doing more than downloading information and task instructions. Students are actually creating their own knowledge. They are writing essays that apply general concepts to their own experiences and interests; they are doing original research; they are questioning their own assumptions and those of their colleagues, the writers they are assigned to read, and their instructor. In doing all this, students are developing the habits and the experience to be able to create knowledge for themselves long after they’ve left the classroom, no matter what the subject area.

A good class must function well at each of these three levels. Yes, the tasks and grading must be well organized to support mastery of the subject matter. But this is the starting point, not the end point. More importantly, familiarity with the subject matter provides a jumping-off point for students to undertake their own investigations and make their own meaning. Think of a soccer team training for competition. It is not enough for the players on that team to be able to repeat a series of factoids about how the game is played. It’s not even enough for them to be able to run a set of plays that their coach has devised. In the real world of a real game, they need to be able to, on their own, assess the situation, improvise, and create the best possible approach to the challenge before them. (For example.) My goal as an instructor, then, is to push students to discover and develop their own capacity for building their own knowledge.

What this means for the prospective student is this: you should be ready to think for yourself in my classes, and to be challenged in that work.