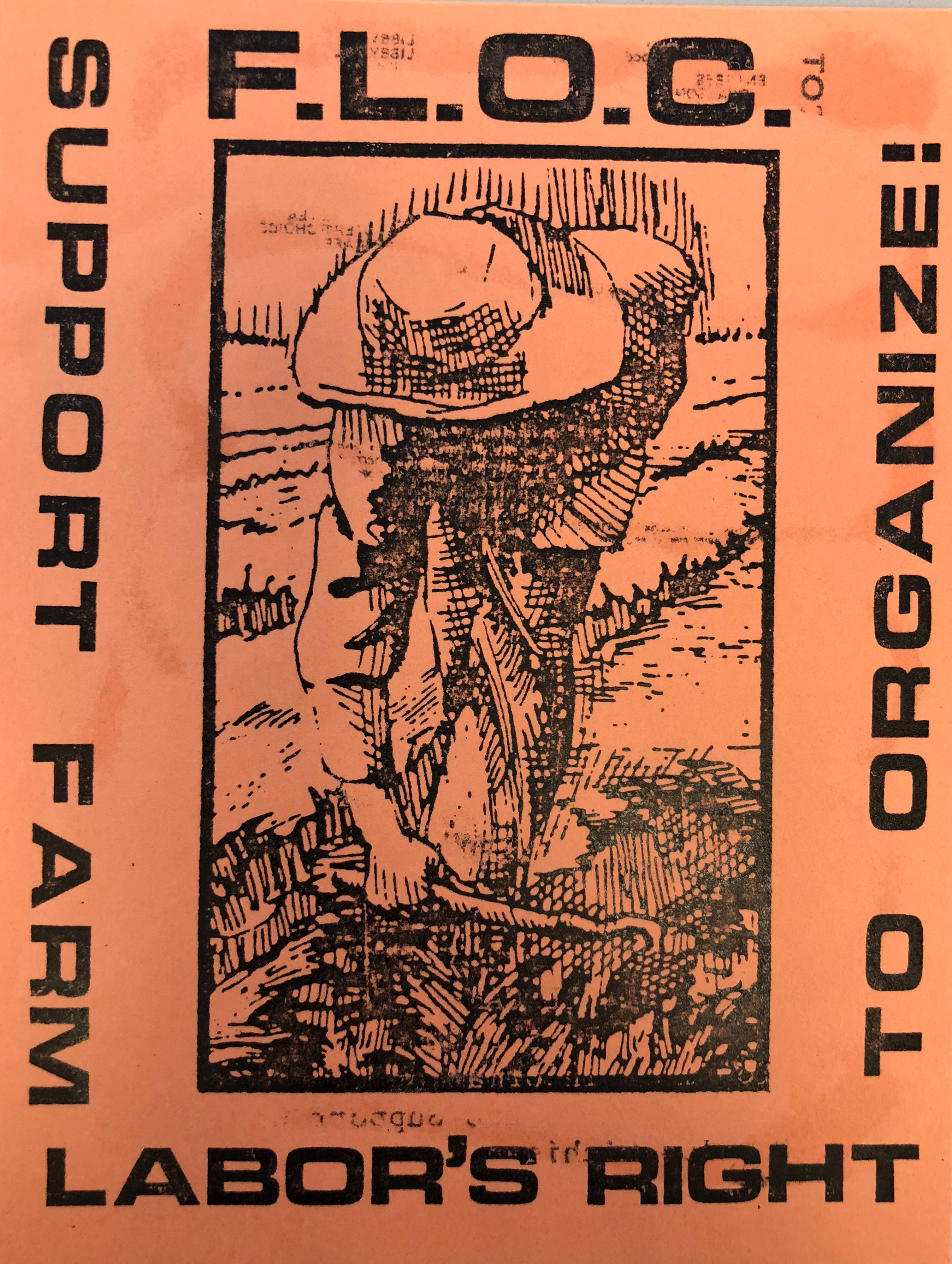

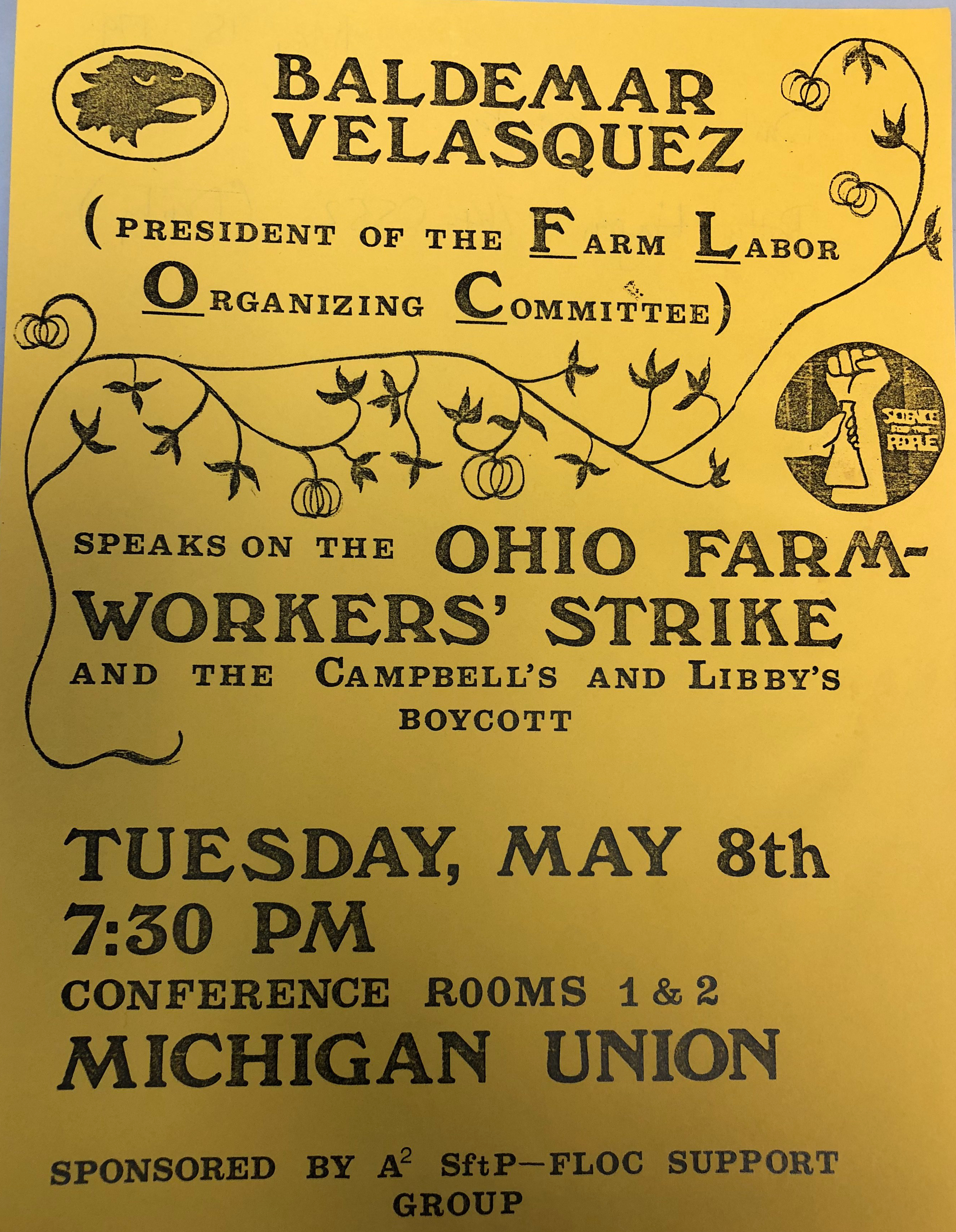

Given the past and current cultural settings to which we live in, there have been many different groups of people that have been label as “Other” in our society. Generally speaking, being labeled “Other” has set apart those who have come from different backgrounds, cultures, and social status and along with those labels these people have faced various forms of discrimination. In order to organize and fight against these hurtful labels, the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC) was founded in 1967 by Baldemar Velàsquez and was successfully recognized as a labor union of farmworkers in the Midwest in 1979. FLOC gained public attention with their numerous attempts to establish a dialogue with the Campbell Soup Company, along with the well-known and established canned food company Libby’s.

This is a short summary of the struggles faced by FLOC workers and supporters in the Midwest region (more specifically the University of Michigan).

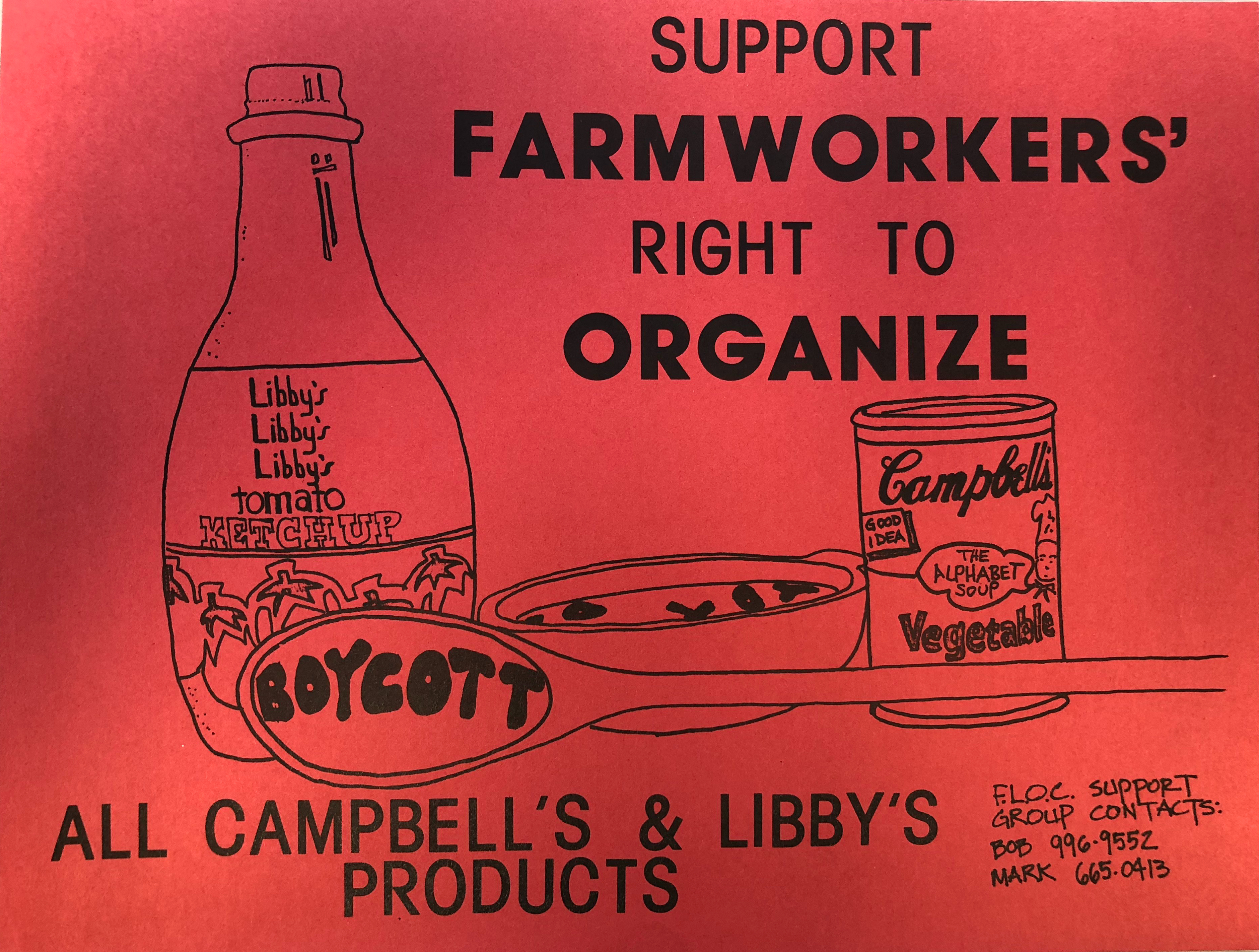

With the decision to strike against Campbell’s tomato field operations in the northwestern region and all Campbell Soup products, FLOC called upon public support in the form of a citizens’ boycott. The rationale behind this movement was to give more support and power to the farmworkers whose painstaking efforts were the backbone of the desired industry. Workers also suffered harsh conditions related to the industry, these conditions included low wages, inadequate housing, child labor and constant exposure to pesticides.

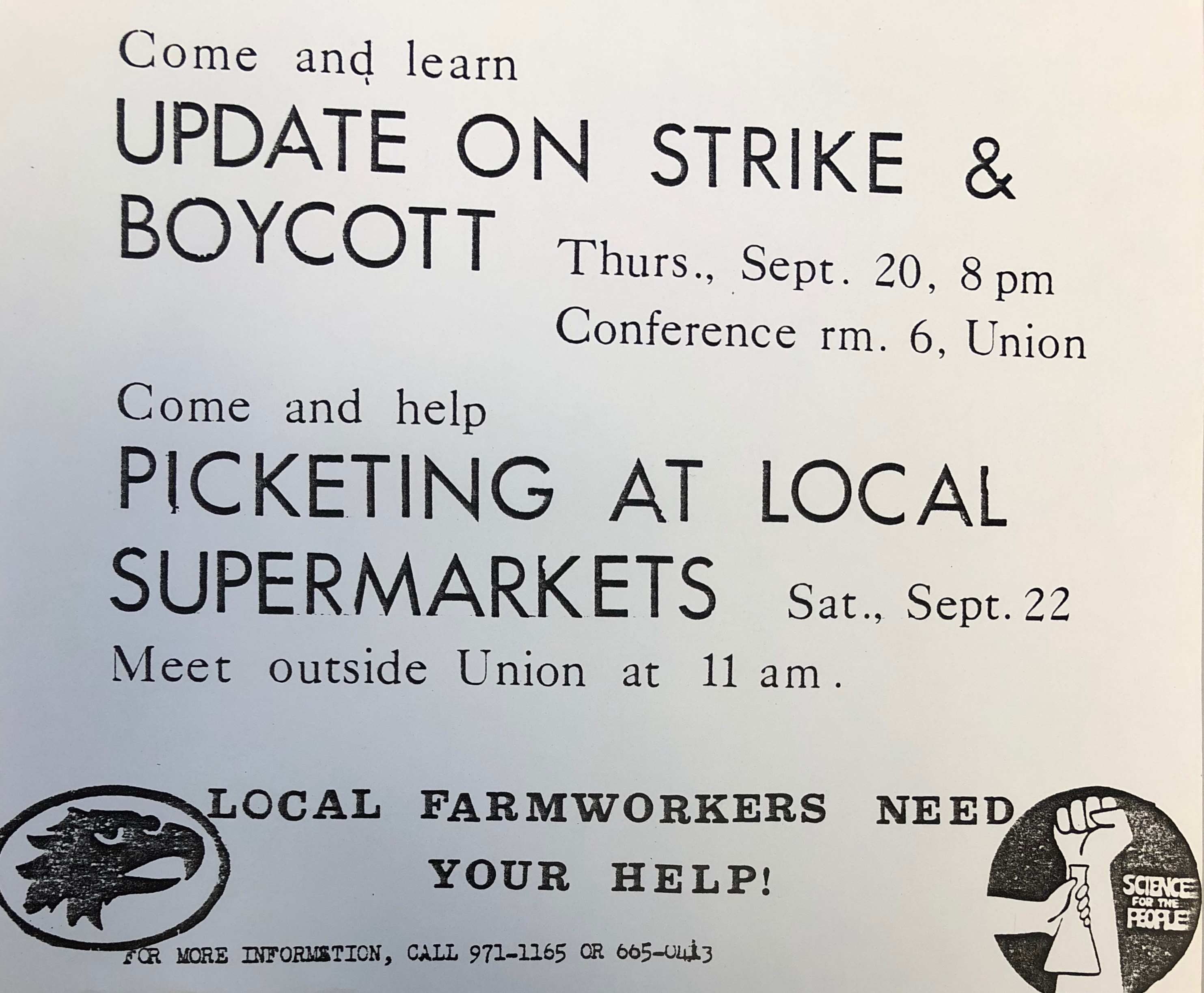

The Ann Abor Michigan FLOC support group played a pivotal role in the strike by working tirelessly to inform people throughout the local towns of the boycott against Campbell’s and Libby’s products. The members helped raise funds, provided supplies for the farmworkers families, conducted research and even printed information on pesticides for the farmworkers. Some members who were enrolled at the Law college even provided legal aid for farmworkers, while the rest went so far as to join in strike activities as far as Ohio. In order to play their part, members of the University of Michigan FLOC support group engaged with fellow students and community members by thinking of creative activities that gave their group local visibility. They created dozens of flyers, newspaper stories, editorials and local radio spots. The literature they provided to consumers of Campbell products enabled them to gain momentum that otherwise wouldn’t have happened. Picketing local supermarkets and food chains was an important task given to the U of M group. This was the time they had to really spread the word by building enthusiasm within the community. FLOC groups used slogans such as “Farmworkers put the good on your table, help them get their rights”, “Mm-mm boycott”, and many others. Singing and chanting on the picket line not only built enthusiasm, it also gave them increased visibility to a noble cause.

Members of FLOC also utilized the local paper (The Michigan Daily). It was here that the bulk of short articles about the boycott were published and spread locally to keep people informed.

January 29, 1979 was an important date for the Ann Arbor FLOC movement because national FLOC representatives came to Ann Arbor to ask consumers to assist with their rights. Roughly 30 migrant workers, some from as far away as Florida, picketed a local Kroger store and asked everyone not to purchase Campbell’s or Libby’s brand food products. FLOC President Baldemar Velàsquez said the boycott probably wouldn’t hurt the companies economically but would raise more awareness of where their food comes from and the human suffering behind their favorite products.

Shifting the focus now to a few selected responses from both Campbell’s Company and Libby’s, we can see how they liked to pass the blame to someone else. In many instances, they agreed with the issues FLOC stood for yet held their ground that they were not at fault.

From a written statement provided by Campbell Soup Company in May 1979, we learned that not only did Campbell insist they do not employ any migrant laborers, they in effect had no connection with the demands FLOC was fighting for. They also stated that Campbell’s should not and will not inject itself into the labor negotiations between their supplier and organization representing the employees of these suppliers because “We seek the goodwill of both suppliers and their employees because both are vital to a supply of materials we need to produce our products.”

In June 1981, Libby’s stated they were no longer involved in primary tomato processing anywhere in the United States, and when they were involved, they believed were they to interject with the conditions faced by the growers, they would have been “Wrongfully inserting Libby into the situation as an arbiter.” In short, they supported the growers’ rights to better conditions and pay, they just believed to remain totally uninvolved and neutral.

Bringing this short summary to an end, I think it’s appropriate to note that life is not easy. Those who struggle must have perseverance and above all else confidence in the belief that real change can be obtained. The members of FLOC had that perseverance, and it was shown through their accomplishments with the Midwestern farmworkers. The overall collective bargaining agreements that came to light from ongoing striking, boycotts and public support provided a new structure where the common worker became an equal partner in deciding what benefits they will accept for their labor.

On Feb. 20, 1986, FLOC issued a press release headed, “FLOC Signs Three-Way Contracts with Campbell and Growers.” It began, “We have a great many people to thank for their help in gaining these contacts, not the least of whom is Ray Rogers… Campbell has never moved so fast as in the past year and a half during which the corporate campaign was operating.” FLOC workers now enjoyed considerable improvements in their working conditions and also enjoyed an increase of up to 25% in wages and incentive payments. The contracts signed on Feb. 19 by FLOC, 24 Midwestern farmers and the Campbell Soup Co. covered farmworkers working in the tomato and cucumber fields of Ohio and Michigan. FLOC was able to announce that “the tomato and cucumber contracts include insurance policies, wage increases, 48-hour grievance resolution, paid union representatives and the establishment of committees to study the issues of pesticide protection, housing, healthcare, safety and daycare. Furthermore, the contract provides for a special committee to work on a phase-out of the exploitive “sharecropping ” system in the cucumber fields.”

There is a remarkable degree of personal growth and personal satisfaction with those who were involved in the FLOC movement to improve farmworker’s labor conditions. I look back on those who were instrumental to the success and am quite proud of the University of Michigan students who recognized an injustice and took the necessary steps to correct them. Through leadership and organization, a deeper and broader development of social relations were formed and ultimately changed the lives of many people.

I would encourage readers that are interested in further developing their knowledge of FLOC and how students/faculty at the University of Michigan helped to promote change. There are numerous research projects, papers and other documents linking FLOC to Ann Arbor and the university all of which were equally important to the movement.

Sources & Links:

- http://www.floc.com/wordpress/

- http://www.floc.com/wordpress/about-floc/

- https://digital.bentley.umich.edu/midaily

- http://bentley.umich.edu

.