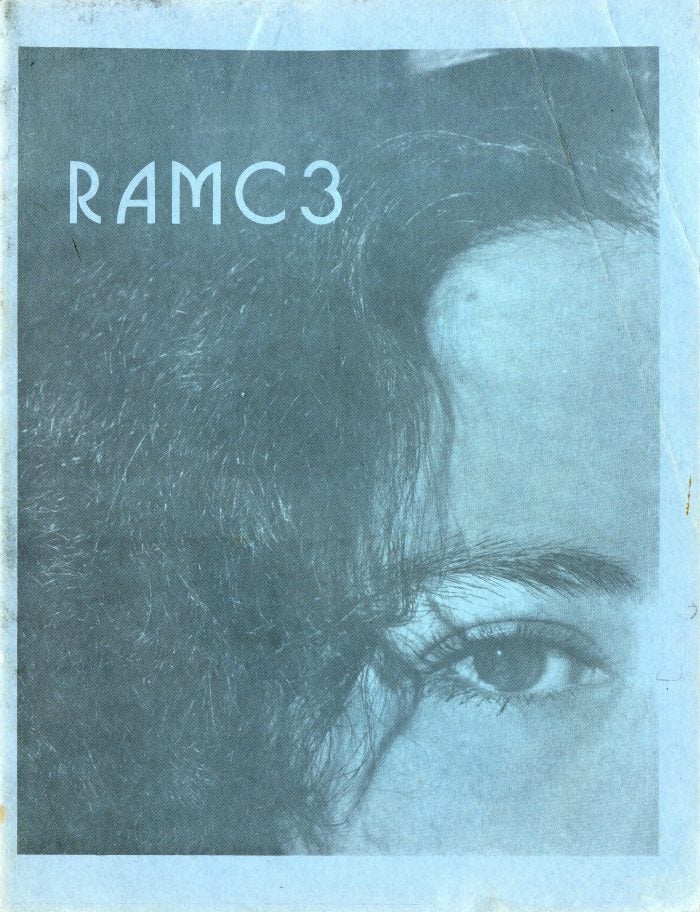

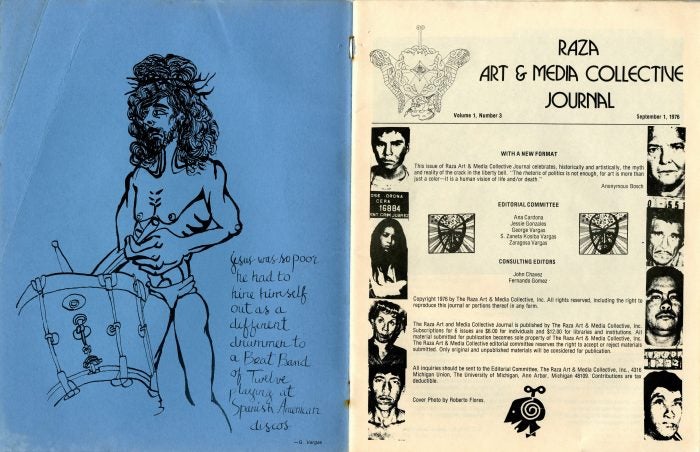

The Chicano movement history has largely been painted as a Southwest/West Coast phenomenon. Even famous Chicano poet Alurista commented after the Denver National Youth Conference of 1969 how, “he was surprised to learn that Mexicans came from exotic places such as Kansas City and Chicago.”1 Who would have guessed that another one of those “exotic places” would be none other than the University of Michigan, out of the needs of Latino students with an interest in art and media. In 1974, Michigan students Ana Cardona, Zaragosa Vargas, Michael J. Garcia, Jesse Gonzales, George Vargas, Julio Perazza, and S. Zaneta Kosiba Vargas came together to form the Raza Art and Media Collective (RAMC). Despite their relatively short run from 1974-1977, the RAMC gained national recognition for it’s art journal publication by the same name. Started out of growing frustrations from Art History graduate student Ana Cardona, RAMC pulled together a group of Michigan based artists interested in carving a space within an institution that neglected their needs as Latinos. Proud Nuyorican Ana Cardona insisted on the use of the term “Raza” in RAMC because it was more inclusive of all Latinos. For her, it was important that RAMC as an organization not be limited to Chicanos or the larger Chicano Movement terminology. The more inclusive terminology would extend to build solidarity among all Latina/os peoples.2

This historia examines the Raza Art and Media Collective through the archival collections of the Ana Cardona, and George Vargas at the Bentley Historical Library, oral interview with Ana Cardona recorded in the Chicana por mi raza archive and interview with George Vargas. These materials help tell a three-part story about an important regional Latina/o art movement that intersected with RAMC members Felipe Reyes and Santos Martinez of San Antonio’s Con Safos art group; LA based performance art group ASCO; and the later contributions of younger member George Vargas and his involvement in the landmark CARA Chicano Art Resistance and Affirmation 1965-1985.

Early Roots: Flustered Chicano Art Students and MEChA

In Ana Cardona’s oral history she notes that prior to forming the RAMC, she was in conversation with current University of Michigan art graduate students Felipe Reyes and Santos Martinez. Originally from Texas, Reyes and Santos were coming from the then defunct 1972-1975 Chicano art group called Con Safos (meaning with respect). For Cardona and Vargas, their exposure to these artists and their organizing background was very influential towards the formations of the RAMC. Cardona notes that following RAMC volume 1 #2, Reyes and Santos were very invested in the aesthetics of creating a unique arts publication.

was the first time we see the collective publish something far from its initial six page newsletter format. Cardona argues that this desire to create was sparked from a negative review the two artists had received in the first book written on Chicano art, Jacinto Quirarte’s Mexican American Artists (1973). While definitely considered a novel feat at the time, Quirarte’s text was met with some resistance. Upon speaking to RAMC member, George Vargas, he speculates that Quirarte had the laborious task of defining Chicano art at a time when the term was very controversial. He concludes that Quirate’s text, while very important, did not rub well among artists who aligned themselves with the activist initiatives set by the Plan Espiritual de Aztlan.3 In this point in time, even amidst the Chicano movement happening in the background, many artists were discouraged from aligning themselves with terms like “Chicano.” Starting from this rocky beginning, early 1970s, 180s art historians such as Shifra Goldman and Jacinto Quirate had to legitimize what we now know as “Chicano art” by first connecting it to Mexican art history in order to establish it as a discipline.

Prior to the creation of RAMC as a formal student organization, RAMC’s initial members had already became vocal regarding Latino and Raza art. A few years before their first 1976 RAMC publication, RAMC members were featured in a University of Michigan MEChA newsletter titled Art and La Raza. Published in 1974 through the Chicano Advocate office at the University of Michigan, Art and La Raza featured artwork by George Vargas, articles by RAMC members Ana Cardona, Jesse Gonzalez, Felipe Reyes, interview with Julio Peraza, and featured spotlight on 1899 Law School graduate J.T. Canales. Reyes’s article in this newsletter Patronage: Chicano Art and Its Consumption voiced his concerns regarding the role of art among la Raza. For Reyes, the exclusion of Chicano art will continue if artists rely on “gavacho patrons” instead of establishing the importance of art in Chicano within their communities.

Aside from her role as an Art History graduate student at the University of Michigan, Cardona notes how her involvement in the arts extended to her work in theatre. In the retelling of the Felipe Reyes and Santos Martinez collaboration with the RAMC, she notes how her true inspiration for starting a Raza arts organization stemmed from the comfort she felt on the set of a student recruitment video sponsored by the University of Michigan’s Chicano Advocate Office. The short film features a segment where university students play with the genre of Teatro Campesino, a rasquache,4 low budget style of theatre that was popularized by United Farmworker Movement and performed on the backs of pick-up trucks to farmworkers in the fields as a means to educate them on the injustices of non-unionized agricultural labor.

ASCO: Your Journal Disgusts me!

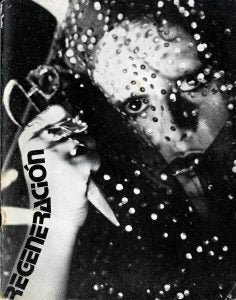

According to Art Historian Olga Herrera, a popular trait of the latter two issues of RAMC were it’s inclusion of the work of the art group ASCO.5 Similar to RAMC, ASCO also had an arts publication. ASCO first started when Harry Gamboa jr. approached high school friends and artists Patssi Valdez, Gronk and Willie Herron to publish the first issue of their publication Regeneracion.6 ASCO, meaning “it (your art) disgusts me,”7 is most notably known for their status as a subversive performance art group playing on public perceptions of what Chicano art is and shouldn’t be.

As a step away from it’s smaller newsletter format, RAMC volume 1, #2 features a call for artists and writers to contribute to the RAMC journal. Immediately after this issue we start to see the black and white collage of ASCO8 appear in RAMC materials. In the RAMC journal we see snapshots of ASCO’s famous ads for their No Movies, fake ads for movies that did not exist but featured ASCO’s members as commentary on the lack of representation of Chicanos in the media. RAMC member George Vargas notes that the exposure of Michigan based artists to the work of ASCO introduced them to a “new wave” of Chicano art and what it could look like.9 RAMC member and American Culture graduate student Zaneta Kosiba-Vargas would later go on to write her dissertation, “Harry Gamboa and ASCO: The Emergence and Development of a Chicano Art Group, 1971–1987,” (1988). RAMC members George Vargas (1988) and Zaragosa Vargas (1984) also graduated from American Culture’s PhD program with dissertations in Latino studies.

Beyond RAMC: George Vargas and CARA Chicano Art Resistance and Affirmation 1965-1985

Although George Vargas was an undergraduate around of the RAMC’s inception, Vargas still managed to be involved and provide artwork for various RAMC’s publications. In the first issue of RAMC, Vargas was the creator of the RAMC logo that would later adorn the group’s official letterhead. Beyond his artistic contributions to RAMC, George Vargas went on to work as an art historian. As a graduate student in the Department of American Culture, RAMC Vargas’ dissertation titled Latino Art in Michigan references the work of RAMC affiliated members and helps historize earlier artists like Carlos Lopez—a WPA muralist in the 1930s who later joined the art faculty at the Art and Design school at the University of Michigan—as important antecedents in the Midwest Latina/o arts movement. Vargas’ time at the University of Michigan undeniably influenced his larger observations regarding the art networks of Latino artists in the Midwest.10

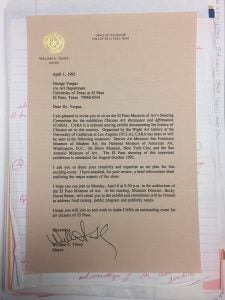

George Vargas’ archive of donated teaching curriculum at the Bentley document his involvement in the El Paso steering committee for the traveling exhibition CARA: Chicano Art Resistance and Affirmation 1965-1985. CARA traveled to ten major cities from 1990-1993, and for the first time in history, U.S. museum audiences got a chance to view a Chicano art exhibition in mainstream art institutions. Although created long after the run of the RAMC, the date range of the CARA exhibit content, 1965-1985, encompasses the aesthetics and art activism that greatly impacted the work and arts initiatives of the RAMC.

So immersed with this moment in Chicano art history, one of Vargas’ assignments in his miscellaneous files is a CARA research paper assignment that asks students to pick an artwork from the CARA exhibition catalog. Vargas notes that this exhibition was the first Chicano art blockbuster exhibition that laid the groundwork for a nuanced definition of Chicano art as American art. Reflecting on his experience with the 1992 CARA exhibition in El Paso, he notes how the El Paso Museum of Art had recently come under fire after a newspaper article documented a museum board member speaking negatively of the work of Chicana artists Carmen Lomas Garza. Involved in the community outreach for the CARA exhibition in El Paso, Vargas notes how the openings reception was so well attended and brimming with Latinx museum visitors who had never seen themselves reflected in the El Paso museum collection. In line with the RAMC commitment to creating and supporting spaces for celebrating and educating the public about Raza art, the CARA exhibition was a major milestone in U.S. history.

Far from the Chicano movement imaginary, the Raza Art and Media Collective is a unique slice of the rasquache art history of the University of Michigan history. Despite it’s Ann Arbor location, RAMC drew from influences and networks that extended as far away as Chicago, San Antonio and LA to create a larger regional network of the Chicano art movement.

Wanna learn more about the topics covered above?

Check out this list of Recommended Reading!

Raza Art and Media Collective

ASCO

McMahon, Marci. 2011. “Self-Fashioning through Glamour and Punk in East Los Angeles: Patssi Valdez in Asco’s Instant Mural and A La Mode.” Aztlan: A Journal of Chicano Studies 36 (2): 21–49.

CARA exhibition

Footnotes

1Ramirez, Leonard G., Yenelli Flores, Maria Gamboa, Isaura González, Victoria Pérez, Magda Ramirez-Castañeda, and Cristina Vital. 2011. Chicanas of 18th Street: Narratives of a Movement from Latino Chicago. University of Illinois Press. (page 1).

2Cardona, Ana. “To Our Audience.” RAMC volume 1 #1 Ann Arbor, (January 1, 1976): 1.

3Phone interview with George Vargas April 22, 2018.

4This term was later used exclusively to refer to Chicano art in an article by art critic Tomas Ybarra-Frausto. Rasquache is a DIY Chicano art sensibility that uses surrounding materials and lived experiences of Chicanos to create art. It is art based in community circulation and in conversation with the quotidian aesthetics of Mexican culture.

5Herrera, Olga. n.d. “Raza Art & Media Collective: A Latino Art Group in the Midwestern United States.” Institute for Latino Studies, University of Notre Dame, Indiana. Accessed March 16, 2018. https://icaadocs.mfah.org/icaadocs/Portals/0/WorkingPapers/No1/Olga%20U.%20Herrera.pdf.

6Chavoya, Ondine. 2000. “Orphans of Modernism: The Performance Art of Asco.” In Corpus Delecti: Performance Art of the Americas. Psychology Press.

7Noriega, Chon. Nov.18, 2010. “Your Art Disgusts Me: Early Asco 1971-75.” East of Borneo. https://eastofborneo.org/articles/your-art-disgusts-me-early-asco-1971-75/.

8 ASCO’s aesthetic was very informed by the cut and paste nihilistic style of Dada movement artists.

9George Vargas dissertation

10Vargas, George. Spring 2915. “¿ Qué Onda?“What’s Happening?” Chicano Art in Twenty-First-Century America

Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies. UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.