LATINX ARTISTS AT MICHIGAN (1945-1980s):

ART AS A FORM OF ACTIVISM

By: Danie Lopez

INTRODUCTION

If you identify as Latinx, how do you make yourself visible on a campus that is not intended for you? Do you start an organization? Organize a rally or protest? Meet with administrators? Ignore the issue? Or Do you channel the injustice through art? There is no right or wrong answer to this question because we are all different and thus express ourselves in our own ways. Being a minority at a predominantly white institution such as the University of Michigan comes with its own challenges so you find a way to overcome the many adversities that come your way.

Like many other marginalized minorities at the University of Michigan, the Latinx community has been neglected for years. In response to this neglect, Latinx students have advocated for change in many different ways. Some protested some met with administrators, and some used their artistic talent to advocate for change. Whether it be through writing, music or visual arts, over the decades members of the University’s Latinx community have used their artistic abilities to build community and recruit new students, to create greater awareness of their culture and to advocate for the needs of Latinx students at the University of Michigan.

These artists helped to create a sense of community for Latina/os at the University of Michigan, from the post-war period to the 1980s, and yet very little is known about them. Their lives demonstrate the intersections between art, activism, and Latinx identity. In this Historia, I focus on two artists, Carlos Lopez who joined the art faculty in 1945, and George Vargas who attended the University some 30 years later from 1975-1980 and whom I interviewed as part of this project. Their different experiences illustrate the many ways that Latinx artists have labored to create community at the University of Michigan.

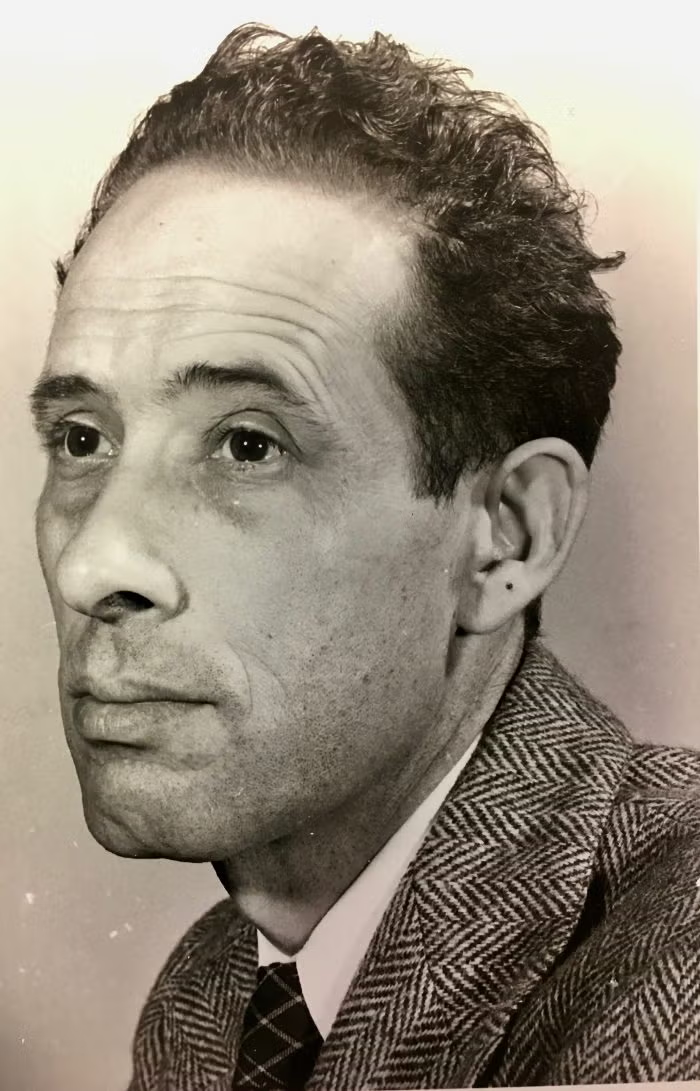

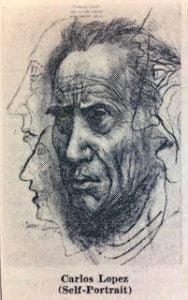

CARLOS LOPEZ (Years at Michigan: 1945-1953)

Painter Carlos Lopez was born in Havana, Cuba on May 24, 1908, but he spent most of his early years in Spain. In the year 1919, at age 11, he moved to the United States where he lived until his early death at age 44. Carlos Lopez spent a year studying in Chicago and then attended the Detroit Art Academy for three years. During the Great Depression, Lopez found work as a muralist with President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. According to the website The Living New Deal, Carlos Lopez painted numerous murals throughout Michigan. For example, in 1938 Lopez painted Plymouth Trail in the post office in Plymouth, Michigan. The painting portrays the historical role of the stagecoach in transportation and mail delivery in Michigan’s history (Vargas). Not only did he make a valuable artistic contribution to the state of Michigan but his images helped shape its history and later, that of the University of Michigan.

In 1945, Carlos Lopez joined the Michigan community at the School of Architecture and Design (now the Penny W. Stamps School of Art and Design). He was to be the only Latinx professor at the School of Art and Design until 2017, when Omar Sosa-Tzec joined the faculty as a junior professor, As a member of the faculty, Carlos Lopez contributed to the Michigan community by creating art that portrayed the history of the state of Michigan and by inspiring his students each day.

In 1946, as part of a collection called “Michigan on Canvas,” Carlos Lopez was one of the 10 American artists that drew attention to different areas in the state. Out of the 95 artwork selected, twelve of the paintings chosen for the collection was created by Carlos Lopez. One of his paintings titled, Ann Arbor, Home of the University of Michigan which shows “Ann Arbor residential area on the northern outskirts in 1947, looking southernly towards the university and downtown area.” (UMMA Exchange)) If you look closely at the image you are able to see the Burton Memorial Bell Tower and the University of Michigan Hospital. Carlos Lopez shared his talent with students in his classes, and with the larger UM community through numerous public exhibitions for nearly a decade until his untimely death from a pulmonary embolism on January 6, 1953. The entire Michigan community, especially his students, was affected by his death. Professor Jean Paul Slusser described Carlos Lopez as “…one of the best loved teachers and generations of his pupils will testify to the power and stimulus of his eager and youthful spirit.” Carlos Lopez’s son Jon recalls that his father would often tell his students, “ I can teach you to draw, but I cannot teach you to be an artist.”

Today, the work of Carlos Lopez is displayed at the Detroit Institute of Arts, at UMMA, Washington D.C, and many post offices in the state of Michigan. From his work as a WPA artist to his time at the University of Michigan, Carlos Lopez created community by embracing the regional cultures and histories of the State, while his work was not focused on his Latinx identity his contributions to the aesthetic landscape of Michigan nevertheless influenced a more radical generation of Latinx artists who were to come.

GEORGE VARGAS ( Years at Michigan: 1974-1989)

Artist and Art Historian George Vargas was part of a more radical generation of students who attended the University in the mid to late 1970s. George Vargas initially applied to Eastern Michigan and the University of Michigan. He decided on the University of Michigan because it was the more prestigious school and he felt it would be academically challenging. According to Vargas, he was “one of the few Latinos that took it upon [himself] to apply [to U of M] and that was not unusual because of most Latinos at that particular time… it was recommended that they go into the trades… a mechanic or a teacher… or on the other go into the military.” Vargas originally started in the electrical engineering program because “radio technology was current in [his] days…[so he was] looking to go into something to do with radio.”

Adjusting to life on campus was challenging for Vargas: “The big challenge was to find my own niche… as an emerging art student. However, on the flip side, there wasn’t many, if any Mexican American, Latinos, in my particular program but I managed to maintain an interest… and graduated one of the first, I believe one of the first, Mexican-American art students at this particular time.” Vargas recalls how he negotiated his identity on campus, at first downplaying his connections to the Latinx community “many people did not know who I was because I didn’t look like a Chicano, Latino, Mexican American, and I did not push that because I wanted to be safe. I wanted to fit in sort of speak, so that wasn’t much of a challenge for me. It was eventually my junior and senior year and as a grad student that I became aware of my identity and history that were not really taught in high school… so I took… courses that awaken a consciousness..and developed an interest in Mexican American art history.” Once he became interested in this, he faced many challenges from “professors [who] didn’t understand why I was studying this new movement” because he was not studying traditional art. Thus for graduate school, he studied art history, focusing on Chicano art. However there were other faculties at that time who mentored him along his journey, one of this mentors was Silvia Pedraza, a Cuban-American professor in the Department of Sociology.

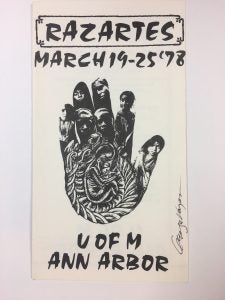

As he became more radicalized, Vargas participated in various activist organizations, some of which focused on the arts. He was a part of Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MECHA) and Teatro de Los Estudiantes, a Chicano theater group lead by Fernando Gomez, a graduate student in the American Culture Program. For the Teatro de Los Estudiantes, “ [he] became more of prop man… and helped with the technical part” and “ For MECHA [he] made flyers and posters.” In MEChA, there were “super Chicanos that proclaimed if you don’t speak enough Spanish you’re not Chicano.” This made him feel unwelcome because he was married to a Caucasian, but he remained apart of this group.

When asked what lead to his interest in activism, Vargas noted that it was his work in the surrounding Latinx community that encouraged him to become more active on campus and in the arts: “I developed an interest in being an activist on behalf of Chicano art. I worked a lot of with the various communities of Michigan, organizing artists and art groups. One of the groups that we formed was Raza Art and Media Collective (RAM).” When asked if there was something specific that led to the founding of RAM, Vargas replied: “Yes, we saw that all the other groups on campus, the arts were being shuffled off to the side. Sure MEChA would approach me to make flyers and poster but did not support us to make an art show. The first show that I was a part of that was Chicano was at the Union gallery…. We decided to form RAM, focusing on promoting, and presenting and preserving Latino Art.” Vargas started RAM in 1974 along with his brother, historian Zaragosa Vargas, and other activists such as Ana Cardona Jesse Gonzalez, Julia Perazza, Michael J. Garcia, and S. Zaneta Kosiba Vargas, to start the Raza Art and Media Collective. RAM’s goal was to give a voice and platform to Chicano/Latino artist and media producers and to combat the invisibility of Latinos in the arts and media as well as the negative stereotypes that circulated in those spaces. The Raza Art and Media Collective was much more than an arts organization, it became an important way to recruit many Californian Chicanos, Tejanos, New Mexicans, and Puerto Ricans to the University of Michigan, and to offer them a sense of belonging once they got here by sponsoring academic events, parties, and exhibitions.

Another purpose of RAM was to bring attention to Latinx arts and artists in Michigan which had been ignored by both mainstream art culture and the national Chicano movement. “We got attention. We got attention and the way that we used our attention was to promote. To not only promote yourself but to promote the greater expression on behalf of the community at large, the Chicano/Latino community at large… we thought that it was enough to create exhibition and.. [make]… publications.” While their publication was not long-lived, it is historically important because it documents one of the few Midwestern Latino arts movements in the 1970s. It also shows how midwestern arts collectives were connected to the broader Chicano art movement.

George Vargas earned three degrees from the University of Michigan. He obtained his Bachelors of Fine Arts and Film ( 1974-1976), Master of Arts in American Culture/ Latino Studies (1976) and his Pd.D in American Culture/ Art History/ Latin American Studies (1988). George Vargas not only instructed and lectured at the University of Michigan but also other institutions including University of Texas at El Paso, Oakland University, Detroit Institute of Arts and the Art Institute of Chicago. He has written numerous books and articles about Chicano Art, and particularly Latinx artists of the Midwest. One of these articles was titled Carlos Lopez: A forgotten Michigan Painter

Like Carlos Lopez, George Vargas has some advice for university students today:

“I encourage students… to do the best they can whatever they are studying whether it be Chemistry, Medicine, Law, or Chicano Studies… [and] to contribute to the community at large… define your own space.”

Sources

Carlos Lopez

https://americanart.si.edu/artist/carlos-lopez-7370

https://jsri.msu.edu/upload/occasional-papers/oc56.pdf

http://www.modernsandiego.com/RhodaLopez.html

George Vargas

http://blogs.detroitnews.com/history/1998/01/30/detroit-is-fertile-ground-for-art/