On September 26, 2016, a white supremacist group calling itself “Identity Evropa” (@IdentityEvropa) used Twitter to announce a new campaign called #ProjectSiege. The campaign would target college campuses across the nation with eye-catching posters designed to glorify white European identity and the politics of the Alt-Right. Pairing glossy images of classical and Renaissance sculptures like the Apollo Belvedere and Nicolas Coustou’s Julius Caesar with phrases such as “Protect Your Heritage,” “Our Future Belongs to Us,” and “Let’s Become Great Again,” the posters drew on the iconicity and cultural capital of the sculptures as an overt appeal to a supposedly “white” classical tradition linked to white European heritage. The University of Michigan was one of the targeted campuses. Identity Evropa posters appeared on central campus alongside other posters with racist messages and distorted statistics targeting Black men in particular. While faculty statements authored soon after the incident specifically refuted claims in the latter set of posters, the visual rhetoric of the Identity Evropa posters was equally damaging for its white supremacist message.

The Alt-Right’s aesthetic and ideological fascination with the trappings of Greco-Roman antiquity is striking, and merits investigation. To give just a few examples that preceded the #ProjectSiege posters, we need only look as far as Twitter or Breitbart, the far-right online news site formerly chaired by Steve Bannon. A popular Breitbart author identified only by the pseudonym “Virgil” has written several dozen articles for the site since 2012, including one that quotes Edward Gibbon’s popular eighteenth-century book The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire as justification for anti-immigration rhetoric. The articles are tagged with an image of Virgil in profile, lending a veneer of classical authority to the inflammatory pieces. Similarly, in July of 2016, white supremacist Milo Yiannopoulos used the Twitter handle @nero while inciting racist hate speech against actress Leslie Jones for her role in Ghostbusters. He was later banned from Twitter for his actions.

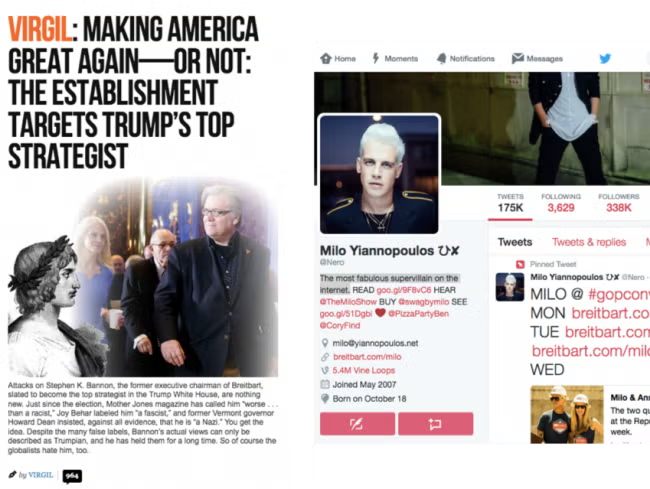

When juxtaposed with the Identity Evropa posters, a clear pattern of identification with Greco-Roman antiquity emerges from alt-right media. Why are these young men—and it is predominantly men—turning to the Classics for inspiration and recruitment? The answers lie both in what Donna Zuckerberg has termed the “self-mythologizing of the Alt-Right,” or its imagined genealogy from Greco-Roman foundations, and in the history of complicated entanglements between Classics and racism in the United States. Identity Evropa self-identifies as “an American based identitarian organization dedicated to educating the people of European heritage about the importance of a Eurocentric identity.” The language of identity and inheritance reverberates through the group’s slogans, chants, and memes: “Protect Your Heritage,” declares a poster featuring the Marble Statue of a Youthful Hercules (69-96 CE); “Our Future Belongs to Us,” says the poster featuring Apollo Belvedere (c. 120-140 CE). In the visual rhetoric of the posters, white male European identity and heritage are explicitly linked to the gods, heroes, and military leaders of Greco-Roman antiquity.

The determined gaze of the young men featured in the sculptures chosen for the Identity Evropa posters mirrors the self-aggrandizing narrative of the men at the helm of Alt-Right organizations. As Apollo and Hercules gaze forward, the captions speak as if from their mouths—an associative rather than factual logic. The Apollo poster projects a narrative of imagined inheritance by the chosen few: “Our Future” stands in as an imagined bulwark against, for example, the projected majority-minority demographic status of the United States by mid-century. The imperative of the Hercules poster—“Protect Your Heritage”—compels those drawn into the white supremacist narrative to take action just as tenaciously as the hero must pursue his twelve labors.

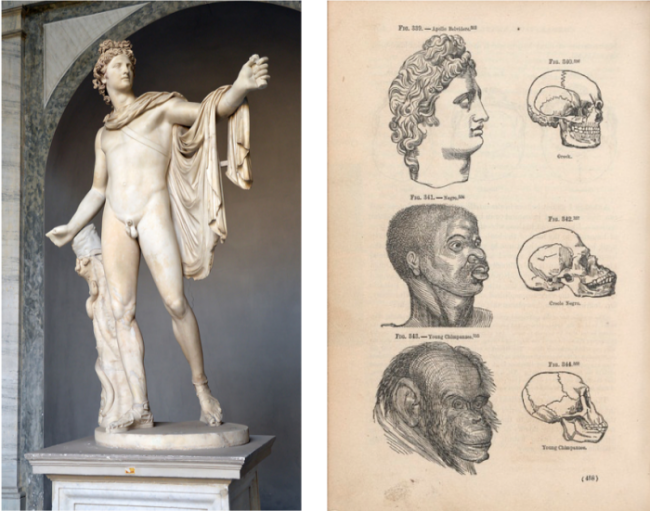

Belief in the “whiteness” of the classical tradition is not new, nor is the conscription of classical imagery and pseudonyms in the service of Eurocentric fascism, imperialism, slavery, and anti-black racism. Hitler and Mussolini’s fascination with the idealized white marble bodies of classical sculptures is well documented, but the trend did not start there. As early as the eighteenth century, proponents of scientific racism used classical sculpture and imagery to degrade and dehumanize non-European peoples.

One of the most blatant examples is the cooptation of the famous Apollo Belvedere into pseudoscientific theories of racial difference. Scientists in the era of European imperial expansion were obsessed with taxonomies and classification, including racial classification. Spurred by archaeological discoveries throughout the Mediterranean, some researchers enlisted classical art and aesthetics—especially ancient sculpture—into an emerging tradition of scientific racism that purported to provide an empirical basis for racial discrimination. The eighteenth-century Dutch anatomist Petrus Camper, for example, explicitly contrasted the nearly-vertical “facial angle” (a measurement from the tip of the forehead to the lips) of ancient Greco-Roman sculptures with that of Africans, classifying the latter as closer to animals. Nineteenth-century writers translated Camper’s findings into derogatory classifications of racial “types,” as exemplified by the racist diagram in Josiah C. Nott and George R. Gliddon’s Types of Mankind (1854) that places an image of the Apollo Belvedere in hierarchical supremacy over the “Negro” and the “Young Chimpanzee.”

Is it any wonder, then, that white supremacists today are repeating the racist strategies of pro-slavery authors like Nott and Gliddon—whom Charles Darwin roundly discredited—in their eager identification with Greco-Roman antiquity? In doing so they are aligning themselves not so much with the ancient Greeks and Romans, but with modern slaveholders, pseudoscientists, Nazis, and fascists. The idea of the Classics as an exclusive European inheritance is a flawed and deeply racist modern construct. It is worth reflecting on what responsibility Classics as a discipline—not just at the University of Michigan, but as a broad and wide-ranging intellectual formation—has in responding to and accounting for the alt-right’s use of the Classics to support white supremacy.

Many classicists involved in reception studies—or the study of how ancient Mediterranean cultures have been interpreted and adapted by writers, philosophers, artists, etc. at various moments in history—are tracking recent events such as the Identity Evropa poster campaign with increasing concern. In June 2017 Sarah E. Bond wrote an article for Hyperallergic about polychromy in ancient sculpture that specifically denounced white supremacists’ fascination with the whiteness of recovered antiquities. She received death threats from the alt-right for her efforts. Writing for the progressive Classics journal Eidolon, Mathura Umachandran called on fellow scholars to redouble their efforts in public scholarship, to “re-imagine the Greco-Roman past in such ways that it cannot serve as a screen for the projection of white supremacy or purity onto it.” For many years, dedicated reception scholars have combated the conscription of the Classics into white supremacist narratives by showcasing the diversity of classical receptions in modern history—see, for example, Michele Ronnick’s traveling photo exhibit “14 Black Classicists” which documents the lives of early African American classical scholars.

Here at the University of Michigan, the Classics department held a “Teach-In” on Martin Luther King Day in January 2017 that responded to Identity Evropa’s poster campaign and made space for public dialogue about Classics, race, and racism. Four speakers, including myself, discussed the topic from subdisciplinary perspectives of linguistics, history, archaeology, and critical race studies. This kind of event is a first step rather than an exoneration; Classics departments must be ready and willing to take criticism as well as to partner with other campus units in taking a stand against hate speech on college campuses. Recent events such as the “Unite the Right” white supremacist rally in Charlottesville last August—which Identity Evropa leader Nathan Damigo helped plan—have underscored the urgency of such endeavors, especially given the alt-right’s target recruitment demographic of college-age white men. On August 8, 2017, Identity Evropa tweeted a fundraising link for a second year of #ProjectSiege, urging followers to “Help us reach college students this fall,” and as recently as October 2017 white supremacist Richard Spencer contacted the University of Michigan to rent a venue to speak. As we as a campus community reflect on our commitments during and in the wake of such events, we need to be ready to counter white supremacist propaganda with the kind of tenacity, intellectual rigor, and historical breadth that the discipline of Classics excels at, and that universities nourish.

—

Heidi Morse is a lecturer in the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies at the University of Michigan. Her book-in-progress, Teaching and Testifying: Black Women’s American Classicism, narrates the hidden history of 19th century black women’s adaptations of classical Greek and Roman literature, art, and rhetoric in the pursuit of racial justice. She is co-editor, with Ian Moyer and Adam Lecznar, of Classicisms in the Black Atlantic (Oxford University Press, forthcoming 2019) and has articles published or forthcoming in Comparative Literature, Legacy: A Journal of American Women Writers, and Oxford Bibliographies in African American Studies.