Author: Kassandra Ogilvie

Student at MacEwan University

Part of the Student Series on the “Brampton Renaissance”

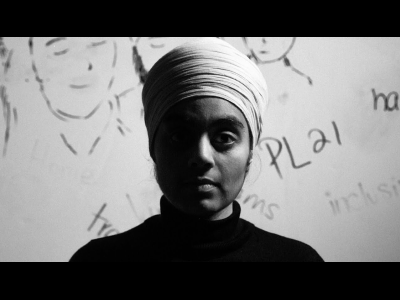

The film Uproar – directed by Amrit Thind & Steeven Toor – tackles the main issues and concerns surrounding Quebec’s controversial Bill 21. Bill 21, the secularity bill in Quebec, prohibits Quebecois citizens from wearing any prominent religious symbols while at work if they work in public service. In the film, many members of the Sikh community as well as Quebecois citizens who opposed Bill 21 discuss their views on the bill. The film moves from interviews with Amrit Kaur, a young teacher who was forced to move from Quebec to British Columbia after Bill 21, and Baltej Singh Dhillon, the first RCMP officer who won the right to wear a turban as part of his uniform, to various nursing students who all oppose Bill 21 and its effects on the community. The various Sikh community members in the film describe how Bill 21 has changed their daily lives. The goal of the film was to bring awareness to the effects of Bill 21 on the Sikh community, and to display the inequality that has occurred because of its enactment.

One of the creators of the film, Steeven Toor, visited our class on February 10th, 2022. When asked about the interview process, Toor admitted that it was difficult to find people who supported Bill 21 but were comfortable discussing those views for the film. The only person who agreed to an interview about his support of Bill 21 was a close friend of the Kaur family: a university student named Sebastien. Sebastien supported secularism in the following comments he makes surrounding people’s ability to perform their jobs without bias: “If you can’t leave these symbols at home to do your eight hours of a judge or become a judge, then how can we trust you to be unbiased at work?” (Uproar 19:43 – 19:55). Sebastien argues that he feels this way about all religion, even Christianity. Yet as has become apparent within the cultural climate of Quebec in the past few years, the Bill does not impede the lives of Christians to the same degree that it does in the Sikh community.

When I first saw the film, I found Sebastien’s comments surprising; it is disheartening to see a well-educated university student agree with a bill that restricts the rights of citizens on the basis on their religion. However, as an overwhelming 64% of the Quebecois population support Bill 21, Sebastien cannot be held personally responsible for his views. He is the product of years of secular sentiment and the approach to multiculturalism that Quebec has adopted in the past fifty years. Quebec boasts a long history of nationalism, and the downside of this approach to politics is how this push for more independence has led to the secularism that currently inhibits the religious populations of Quebec (Béland et al. 168).

Secularism, often understood as the practice of separating the state from religious ventures, relies on the discourse of preventing religion from impacting state affairs. Secularism manifests as a push towards neutrality, and the key is to restrict display of prominent religious garments or accessories in the defense of a more equal state, as has been observed in Quebec. Some of the logic behind this is that if women are not allowed to wear hijabs they will be considered more equal to their male peers, and there’s also the assumption that openly displaying one’s faith will make them less fair in how they conduct themselves at work. All of this to say: the assumption is that religion will impede in the legitimacy and equality of state and personal affairs.

Secularism stems from a history of both imperialism and colonization. It represents a symptom of the idea of religion-making: the institutionalization and rationalization of certain practices as “religious” to codify religion on a wider scale (Mandair and Dressler 3-8). Secularism requires religion to exist despite the point of secularism being to eschew religion completely. The point of secularism is not to ban religion from politics, but instead to regulate how religion appears in political manifestations (Mandair and Dressler 22). Religion provides a way for a government to commodify and control its constituents, as it can be easily distinguished and therefore regulated. Because it is assumed that all people have a religion, it is assumed that religion can be used to mold a society. White supremacists use this to their advantage by arguing that outward displays of religion cause inequality. By portraying the opposition of Bill 21 as a sentiment of inequality, the public believe that they must support the bill to be tolerant. However, instead of championing for a more equal exchange of rights, white supremacists flip the narrative to ensure every individual subscribes to a charter of rights that aligns with white supremacy instead of true equality.

In the introduction to their edited volume on secularism, Arvind-Pal S. Mandair and Markus Dressler discuss the effects of colonialism in relation to secularism, religion-making, and the institutionalization of religion within societies. They state: “Religion is a key feature in the colonial cartography that serves as a cognitive map for surveying, classifying, and interpreting diverse cultural and historical terrains and allows a distinction to be drawn between secular and religious spheres of life” (24). In other words, religion provides an easy target for white supremacists to take advantage of in the pursuit of multiculturalism, or rather the promotion of white supremacy under the guise of equality. Supremacists have learnt how to position religion as a detriment to society, and instead pose secularity as the solution to the problem they have created themselves.

In the case of Quebec with Bill 21, secularism has been used as an excuse to soothe the “anxieties” that many Quebecois people have towards the increased migration and immigration to Quebec (Béland et al. 178). By creating a “neutral” state, Quebec argues that the uniqueness of Quebec can be preserved as “multiculturalism” (diversity) seeks to erode the natural independence of Quebec as a province (Béland et al. 192). While these ideals have been heavily opposed by the greater population of Canada, Quebec’s apparent fear of religion will continue to guide their politics and their people. While it’s disappointing to see students such as Sebastien fall victim to a thought process influenced by colonization, instead of passing undue judgement on these people, the focus should be on making changes to the so-called equality bills which continue to affect the lives of Canadians. This is the goal of Uproar, as the film aims to expose the faulty logic of Quebec’s secular bill and demonstrate how its plea for equality is in fact a guise for white supremacy.

Kassandra Ogilvie is a 4th year English and Creative Writing student at MacEwan University in Edmonton, AB, Canada. This blog post is the final project from her class, “The Brampton Renaissance,” taught by Dr. Sara Grewal, which covers Sikh artistic and cultural production coming out of Brampton, ON. Kassandra enjoys writing in all forms and is passionate about using the knowledge she’s gained in post-secondary to attempt to make the world a better place.

Works Cited

Béland, Daniel, André Lecours, Peggy Schmeiser. “Nationalism, Secularism, and Ethno-Cultural Diversity in Quebec.” Journal of Canadian Studies, vol. 55, no. 1, 2021, pp: 177-202.

Dressler, Markus, and Arvind-pal Singh Mandair. Secularism and Religion-Making. Oxford University Press, 2011, pp: 3-36. EBSCOhost, ezproxy.macewan.ca/login?url=https://library.macewan.ca/full-record/cat00565a/7934358.