By Matthew Woodbury, Doctoral Candidate, Department of History

As a historian, when asked to explain what I do, one reply is to say I study change and continuity over time. This month that methodological approach takes a personal turn; there are a few changes on my horizon as I reach the final weeks of my doctoral studies and finish a research assistantship with Rackham Graduate School’s Humanities PhD Project. Like the end of a calendar year, the conclusion of an academic year is an appropriate moment to celebrate successes, consider what could have been done differently, and develop next steps.

Last August, during my first week of work on the Humanities PhD Project, April 2018 occupied a distant future. Plotting out the months ahead, I prioritized developing outreach to faculty, gathering examples of graduate coursework designed with career diversity in mind, and posting resources useful to graduate students considering a broad range of humanities careers. Faculty might seem like a counterintuitive place to start for a project designed to serve doctoral students, but professors’ dual role as both career mentors and academic supervisors makes their engagement with, and knowledge about, careers in the humanities of utmost importance.

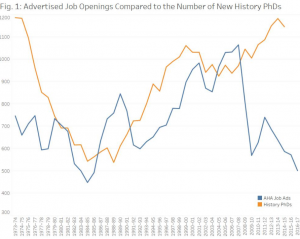

Presenting to department meetings and attending workshops about graduate curricula revealed that most faculty recognize the discrepancy between numbers of doctoral graduates and the availability of tenure-track jobs like the ones they themselves hold. As experts in their disciplines, however, many were also reflective about the limits of their training. How, for example, could a professor advise a student about consulting or non-profit management? How active or directive should departments be in preparing their students for a range of post-graduate outcomes?

In my conversations with faculty, I stressed that advisers and departments need not take a hermetic approach to supporting students in career exploration. University units like Rackham’s Program in Public Scholarship and the Career Center can assist with finding, applying to, and funding opportunities across a range of fields. Online initiatives like ImaginePhD and the VersatilePhD have links to resources suitable for a multitude of employment outcomes and can fill in gaps where faculty expertise and experience falls short. What faculty can do – and perhaps should do – is support students by approaching graduate education as both an undertaking in cutting-edge research and as an opportunity for developing a range of broadly-applicable skills. A summer spent working at a museum or consulting for an advocacy organization, for example, can help inspire or sharpen research questions while providing experience in applying for grants, managing a research program, and writing for diverse audiences. These skills are useful for a host of instructional and research roles as well as in a wide array of humanities careers.

A second thread of my conversations with faculty focused on being creative with graduate coursework. By allowing students to explore, engage, and write in ways that translate to a range of humanities careers, coursework can develop specialist knowledge while also involving participants in collaborative, interdisciplinary, or community-focused projects. Employers look for candidates with applied experience in – rather than only abstract knowledge of – a slate of skills. Gaining both experience and expert knowledge is essential for preparing graduate students for a range of humanities careers – coursework can help achieve this goal.

While many professors are comfortable with the idea that there is value in preparing students for careers outside of the professoriate, reactions to “career diversity” programming were more mixed. Concerns included taking time away from specialist seminars in exam fields, questions about what arrangement of department personnel would facilitate training and support innovative coursework, and whether or not career diversity programming would be mandatory or elective.

There is no one-size-fits-all pattern for how departments might implement career diversity. Budgets, cohort size, and curricular priorities create different constellations of possibility. Following the MLA’s Connected Academics initiative, however, starting small with a modular approach is a good first step with low startup costs. Introducing assignments like an op-ed, book review, or small digital exhibit as part of existing coursework creates a diversity of assessments and experiences. Modifying existing projects to be more collaborative through group work, or including a component involving a partnership with a community group or university department, adds an additional dimension to core practices of research and writing.

Students draw encouragement from seeing their advisors and program leadership express enthusiasm about a range of degree outcomes. This could take the form of including alumni not in R1 positions in department events and programming, providing support for students pursuing internships, and thinking creatively about how coursework can cultivate a range of skills. While some candidates working toward a PhD have a clear and unwavering commitment to either the professoriate or a role outside of the academy, others express an interest in all outcomes or see their perspective shift one way or the other as they progress through the degree. Students also recognize that even the best-prepared graduates struggle to obtain secure academic employment. A prudent course might be one that includes preparation for research and teaching alongside opportunities to gain experience with other manifestations of research, writing, and communication. Fundamentally, skills useful for humanities careers make for better professors.

Among graduate students, the sharing of knowledge about how to find and pursue career diversity is not yet enmeshed within inter-cohort networks. There are (uneven) precedents for talking about prelims, dissertation writing, fellowship applications, and the academic job search. From my perspective, awareness among graduate students is still inchoate about opportunities that readily translate to arenas outside of research and teaching at institutions like the University of Michigan. Visible support from programs would, by broadening the range of outcomes that faculty and students discuss within a department, help normalize conversations about a variety of humanities careers and encourage such discussions among and between students and faculty.

While advocating that departments move toward an academic culture that recognizes the success of all their graduates, doctoral students must also take an active role in charting and achieving their career goals. This process requires significant introspection and reflection about what kinds of environments, timetables, and structures facilitate meaningful work. It cannot be the exclusive responsibility of academic mentors and departments to arrange these opportunities; this task is very much ours. From actively building concrete skills (like how to make a CV out of a resume or what it means to do an informational interview) to assembling a portfolio of experiences (through graduate certificates, internships, or teaching and mentoring), it’s important for doctoral students to feel empowered and take an active role in shaping the contours of their experience and trajectory. Many of the alumni I have spoken with or interviewed emphasize the importance of trying something new, getting out of one’s comfort zone, and talking with people in a range of fields to learn about how humanities PhDs have found fulfilling careers in a wide range of fields.

Eight months after beginning my research assistantship there certainly remain aspects left undone or at which I fell short. The university is a large institution with many moving parts and over two centuries of precedent. At its quickest, change is only gradual. While my sense is that many humanities departments are taking steps to intentionally support a range of humanities careers, there is still apprehension among graduate students about whether or not advisors will “take them seriously” as scholars upon hearing of their interest in a career outside of academia. If a broadened understanding of career outcomes by faculty recognizes that graduate students bring a range of employment goals to doctoral programs, the gap between advertised faculty jobs and numbers of graduates is also an incentive to prepare graduate students for a wide range of careers. My hope is that individual faculty advisers and department leadership will realize how a broad slate of communication, collaboration, and creative skills can benefit students in whatever career they decide to pursue. One academic institution I interviewed at had a history department of four people. I didn’t get the job, but the administrative experience, familiarity in collaborating with other campus units, and the minutiae of event planning I learned as part of my graduate training would have been essential to succeeding in that environment.

My years as a graduate student at the University of Michigan provided many opportunities for growth. The range of possibilities for what I might pursue next is at once terrifying and exciting – I’m one of those students who is applying to a wide range of careers including ones in teaching and research. Most of all, however, this year has been an affirming one. Completing a dissertation, learning the ins and outs of WordPress, and presenting on new topics have all been moments during which I could reflect and say – “Yes, I can do things.” Amidst all of the conclusions and new beginnings going on this month, I’m excited about continuing to work with students in some capacity and maintaining an interest in how people and societies interpret the past. The skills I have built as a doctoral student will be immensely helpful in both these pursuits. Despite all the changes on the horizon, therefore, my future might well be one of continuity rather than change.

Do you have comments or suggestions for what has worked for your own career path or within your department or institution? [formidable id=”10″]!

More From Our Blog

[rpwe limit=”100″ thumb=”true” length=”20″ thumb_height=”100″ thumb_width=”100″ thumb_align=”rpwe-alignleft” cat=”10″ excerpt=”true” readmore=”true” readmore_text=”Read More »”]