From the presidents who led them to the students who studied there, American universities began as exclusively white, male institutions. For more than 200 years after the first American universities were founded, African Americans were forbidden to study at colleges across the country; only in special cases could women attend but, even then, were not permitted to receive degrees.

Today, a record number of African American presidents and provosts preside over American universities. Women and other minoritized groups are breaking ground every year, holding more degrees and leadership positions than ever before. Yet, these numbers still fall strikingly short of true representation in higher education as universities continue to struggle to uphold the ideals of diversity that they champion.

These shortcomings of American institutions reflect the shortcomings of national infrastructure as a whole. From the civil rights movements of the 1960s to the 2020 pledges for equity and inclusion that began after a summer of racial justice protests, the history of diversity in higher education has been inevitably interlaced with America’s own struggles towards becoming a more diverse and democratic nation. Student activism has galvanized civil rights movements for decades and, in turn, universities have often served as a ground zero for the formation of new democratic leaders and ideas. As the nation continues to push forward on creating the diverse communities that are necessary for a successful democracy, higher education continues to struggle. In today’s case study we take a look at this intertwined story that is still very much alive and continues to shape our nation today.

Student Protests and the Multicultural Movement of the 1970s

The notion of diversity in higher education didn’t truly come about in America until the 1960s. Spurred by the civil rights movements, students and teachers alike began to demand a curriculum that better reflected the ideals of democracy and diversity that the nation was beginning to champion. From student protests to sit-ins, they utilized many of the same techniques that were used in the civil rights era to voice their demands for universities to no longer whitewash their history, but rather create departments and teach material that champion them.

At the height of student activism in the 1960s, one in five student protests demanded an end to racial discrimination on campus. As a result of these numerous demonstrations (including a campus shutdown at the University of Michigan in the 1970s) some of the first African American studies departments began to be established. The first Black studies department was started at San Francisco State College in 1968 after the longest strike in U.S. history to occur on a college campus. After 5 months of strikes and protests that were met with violence and legal pushback, San Francisco State College made a novel commitment to admit more than twice as many students of color the following year, and created departments and classes that focused on the stories of minority communities.

The strike had a resounding effect on the nation. By 1971, more than 500 African American studiesprograms, departments, and institutes had been founded. However, many of these programs remained tokenized as universities shied away from what they viewed as extreme Black nationalism. Although more multicultural content became integrated into the curriculum in the 1980’s, programs that were deemed too radical lost much of their funding and Black studies programs suffered a steep decline overall as a result. Many of these programs were only reestablished later in the 21st century as a result of continued student activism and a new cultural awareness that the remaining Black studies programs had been collectively providing for the nation.

Today, around 450 of these departments and programs remain, along with a legacy of multicultural education that continues to shape and inspire younger generations of scholars and thinkers.

Affirmative Action and the Push for Diversity in Higher Education

As educational content began to diversify in the 1960s, student bodies did too. Many colleges and universities began considering race as a factor when admitting students starting in the 1960s as an effect of the civil rights movement. By 1969, elite universities across the country were admitting twice as many Black students than they had in previous years.

But changes in policy came with backlash as white students went to court to fight for their own admission into college—just two years after affirmative action came into the picture. Notably, in the landmark case of Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, the Supreme Court ruled against having a quota system for choosing the demographics of students to admit, forcing many schools to change their affirmative action policies. Even in colleges where more diverse students were admitted, retention remained low. Although twice as many Black students were admitted to Columbia in 1969, for instance, only half ended up receiving their degrees.

Despite controversies, affirmative action has had a strong historical impact. In 1976, white students made up over 80% of all U.S. college students, but that percentage dropped to 57% by 2016. As the nation continues to diversify, higher education has begun to acknowledge the ways in which language and education barriers can misrepresent a student’s learning and intelligence.

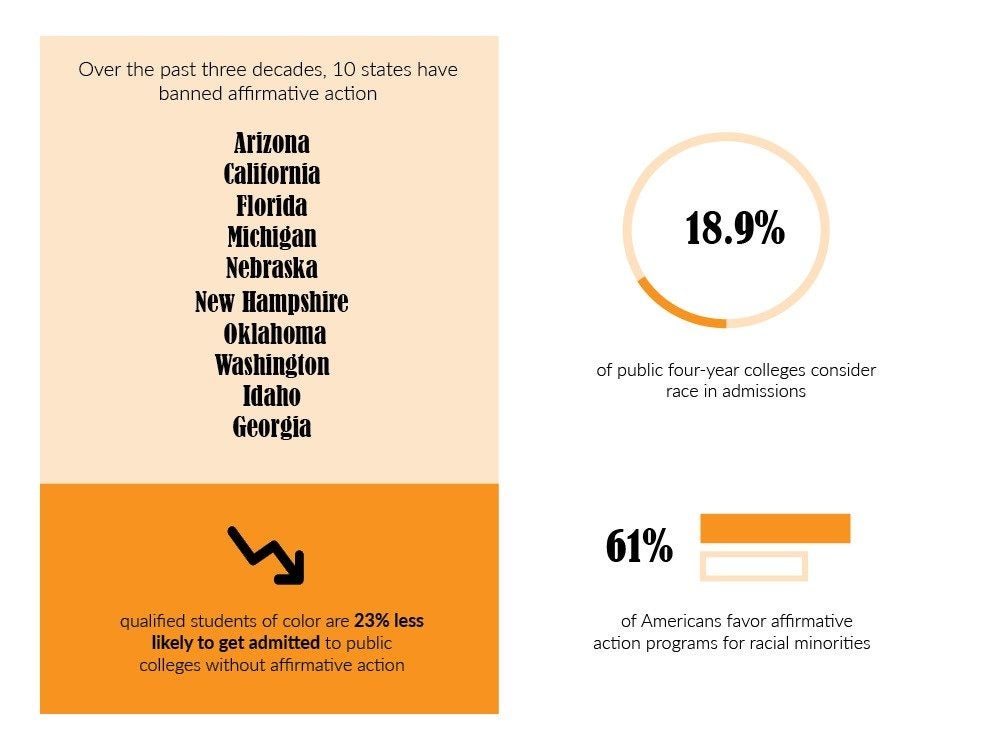

Although the majority of Americans favor affirmative action, the use of race in higher education admission still remains highly controversial. Over the last three decades, 10 states have banned affirmative action and currently only 18.9% of public colleges and universities use race as a factor of admission.

Higher Education Diversity in the Last Decade

While higher education today is arguably the most diverse that it ever has been, the rate of change has been slow. Even as America’s demographics shift and new diversity initiatives continue to emerge, higher education practices remain largely unchanged.

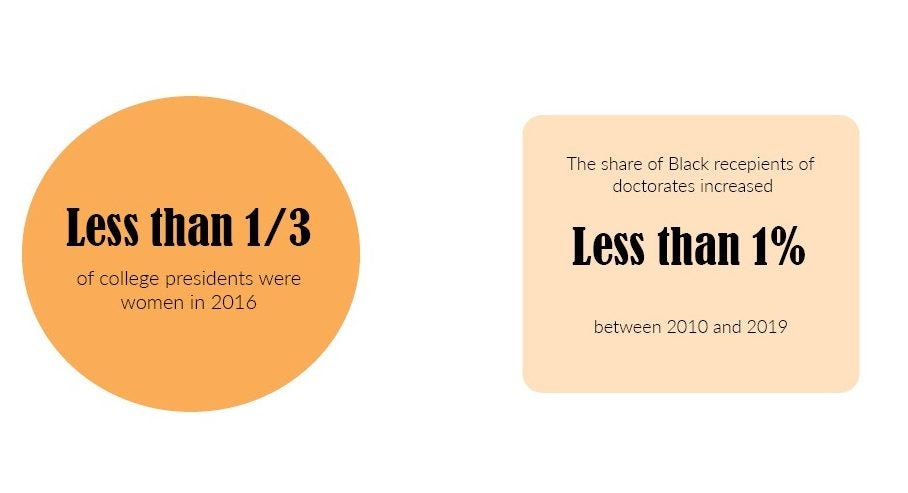

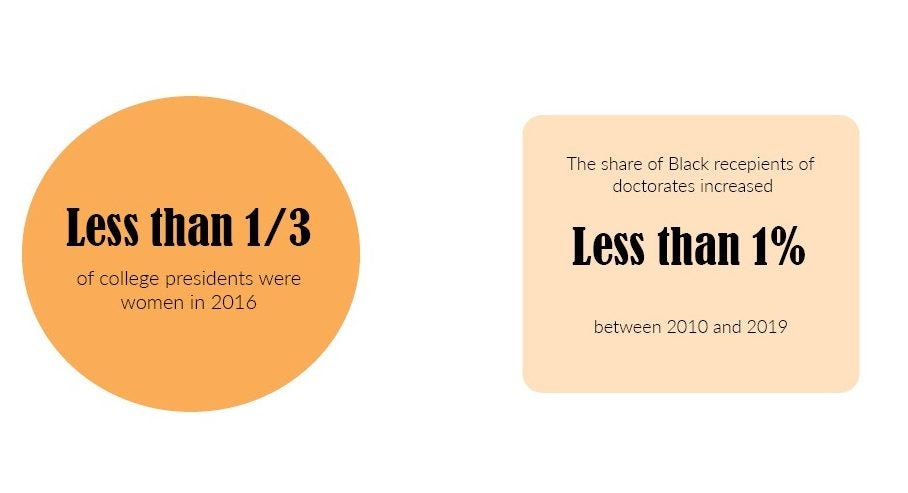

Today less than one-third of college presidents are women and minorities make up only 16% of leadership positions in higher education – percentages which have barely changed in the last decade. Students pursuing higher education degrees continue to face socioeconomic roadblocks; in 2019, many fields graduated only a single Black doctorate holder.

2020 has brought a newfound awareness of the racial tensions in the country following the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and racial justice protests throughout the summer. Many organizations across the nation, including those in higher education, participated in racial reckonings and mea culpas, and have pledged newfound support for diversity and equity initiatives as a result. But even in places where diversity initiatives are implemented, many students and faculty of color continue to feel unsupported. According to a 2020 study, only 58% of Black faculty members felt that their colleges were doing enough to promote diversity and inclusion, in contrast to 78% of their white colleagues.

Looking Forward

As we push forward to a new decade, higher education continues to grapple with many of the same questions that arose from the 1960s.

Is diversity necessary for a thriving democracy? Will universities continue to serve as a breaking ground for the formation of new democratic leaders and ideas? How can leadership in higher education continue to change and better reflect the shifting demographics of the nation and a newfound cultural awareness? Perhaps new solutions lie even beyond the Western academic and leadership tradition itself.