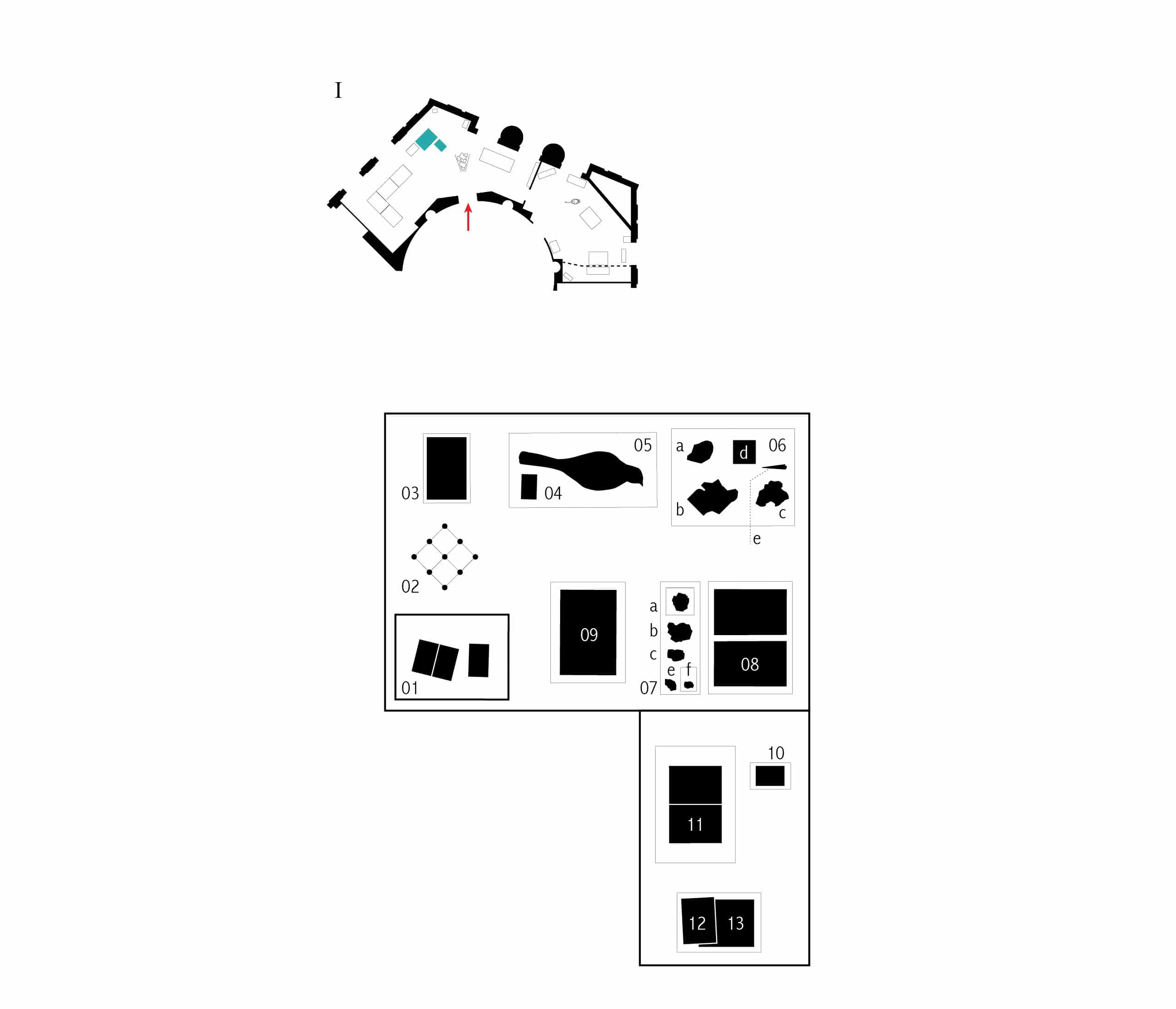

Object Lessons is composed of the following exhibit sections: Geological Survey, Herbarium, Stereographs, Joseph Beal Steere, Collections & Loss, Teaching Models, Alexander Ruthven, Museum Archive, The Cage, The Gates, and Richard Barnes.

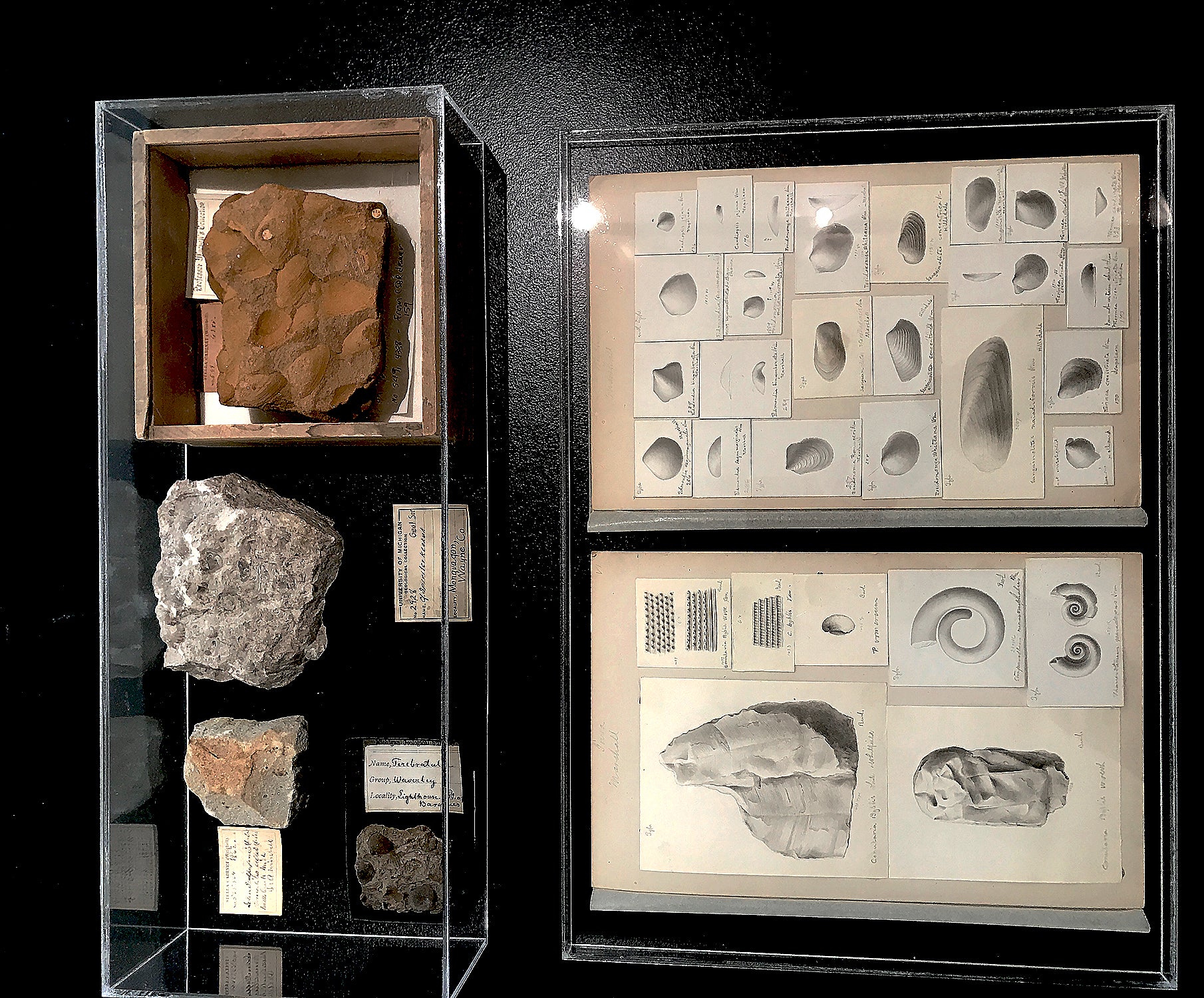

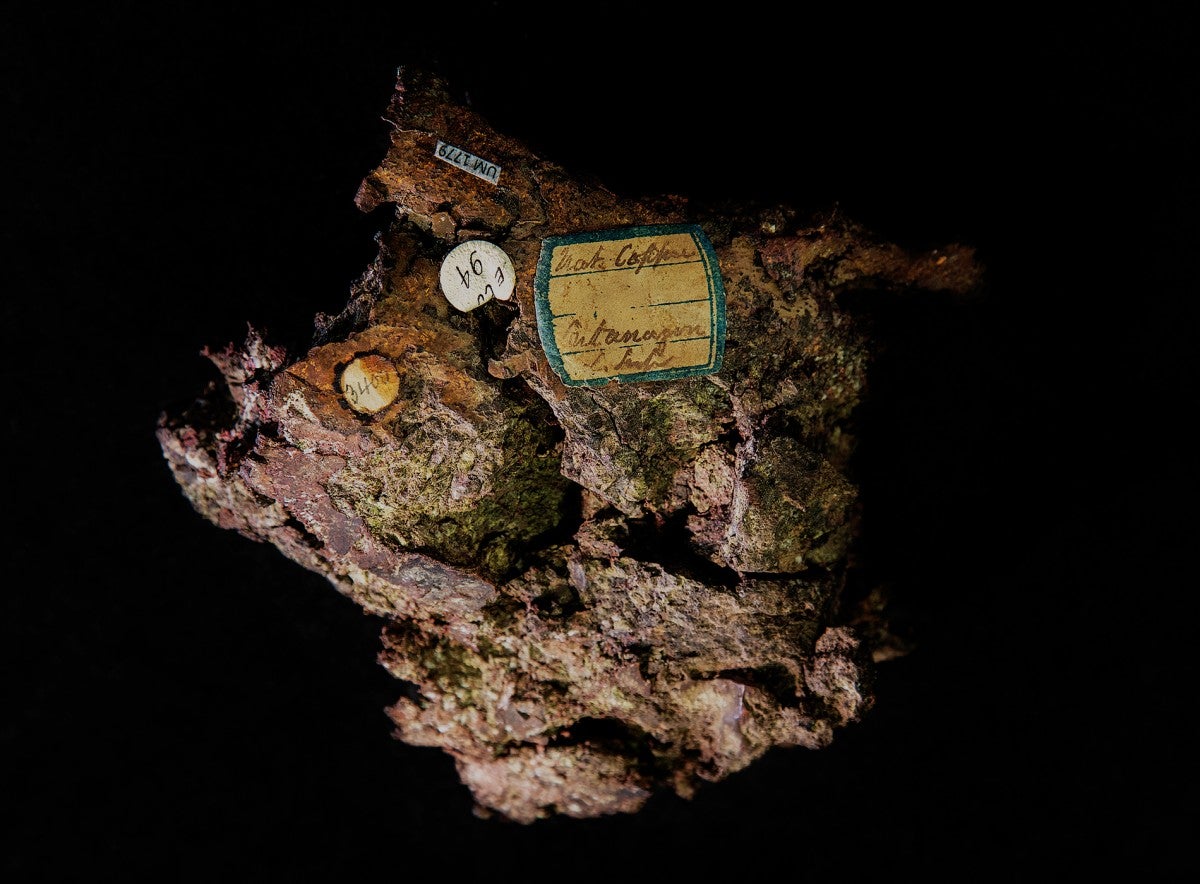

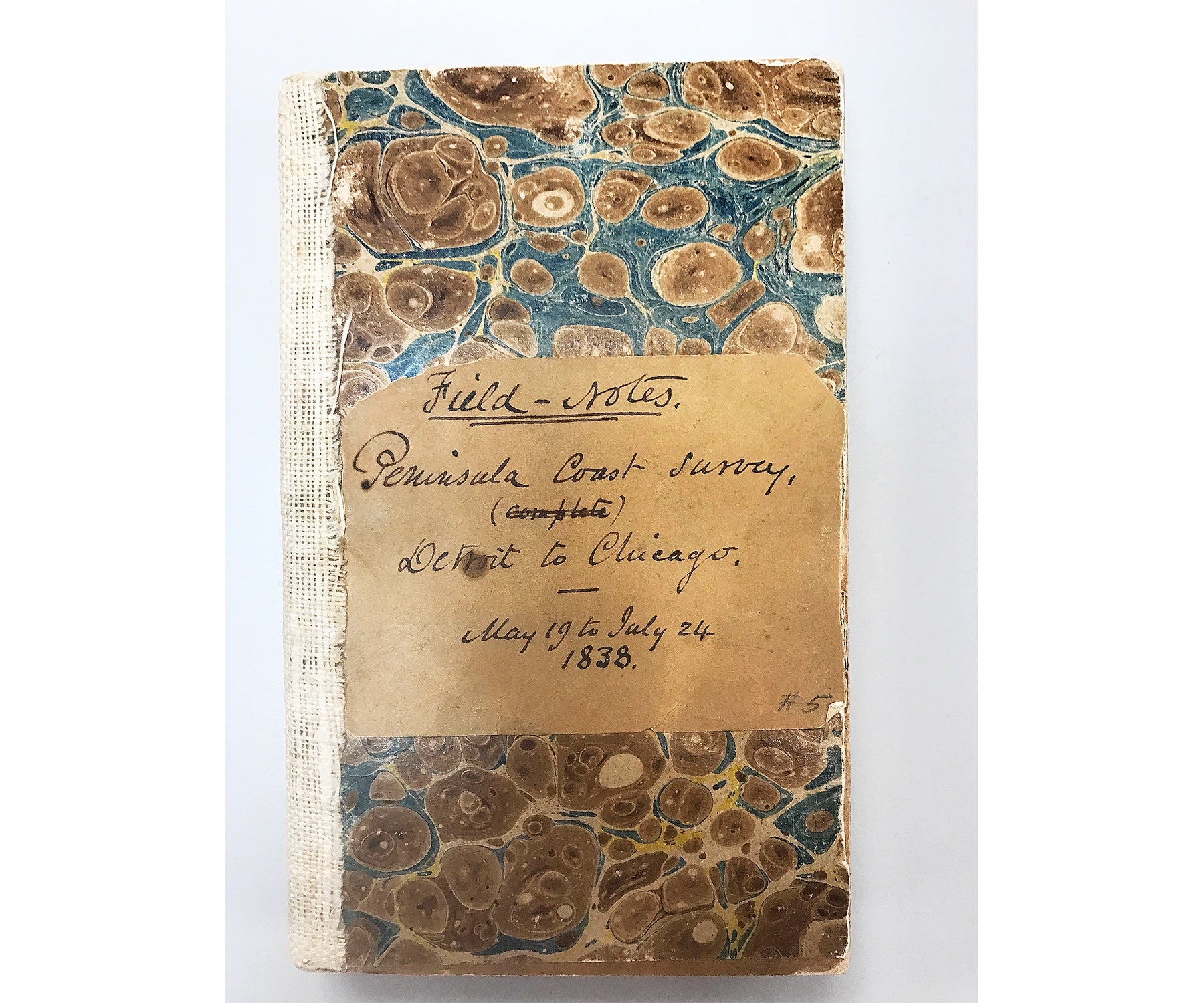

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY

Instituted in the same year of the state’s founding in 1837, Michigan’s Geological Survey forged an early link between the University Museum and the state, laying the foundation for scientific collecting in Michigan in the areas of geology, botany, zoology, paleontology, and anthropology. University of Michigan professors Douglass Houghton and Alexander Winchell directed the first and second state surveys, both of which benefited the University’s museum and research collections and led to a veritable copper mining boom on the Upper Peninsula. The surveys implemented the State’s colonizing quest for “unknown” land and riches, which resulted in the displacement and dispossession of the region’s indigenous Anishinaabe people. Inaugurating a turn to agriculture, mining, and industry, the new settler economy also had destructive effects on flora and fauna. The natural and cultural collections of the University testify to both processes, registering destruction and loss as among the costs of collecting and knowledge production. Both processes also prompted calls for natural preservation efforts that are ongoing today.

HERBARIUM

The plants shown here are part of the original collection preserved in the University Herbarium, dating back to the 1832 Schoolcraft Expedition in search of the source of the Mississippi River. The other specimens on display are prairie plants collected by Douglass Houghton, George Bull, and John Wright between 1837 and 1839 during the first geological survey. In 1840, the legislature stopped funding the botanical and zoological aspects of the survey. The University of Michigan Herbarium nevertheless continued to build its collections through faculty expeditions, gifts, and purchases. Its world class collections feature 1.7 million specimens, documenting biodiversity globally and historically.

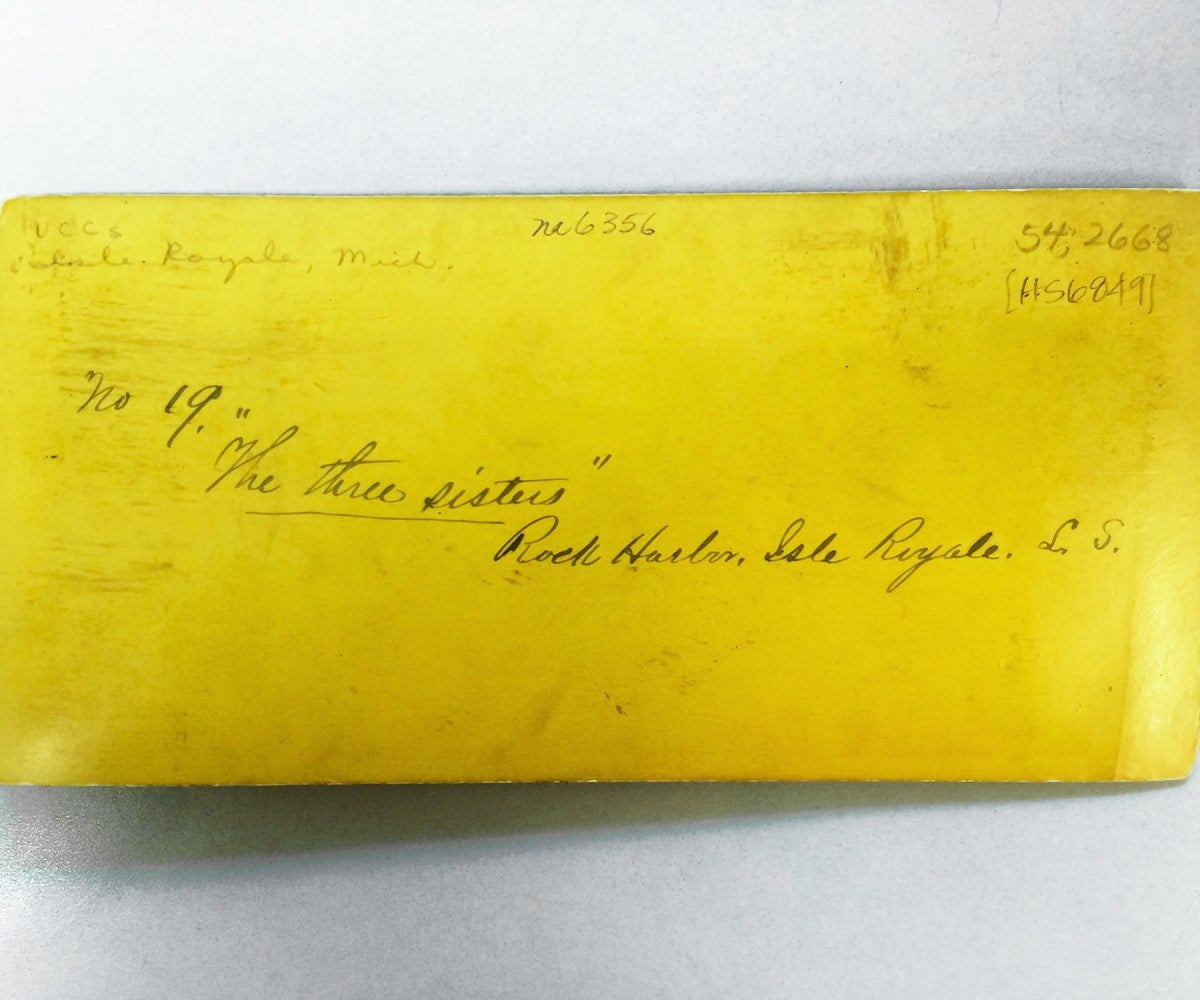

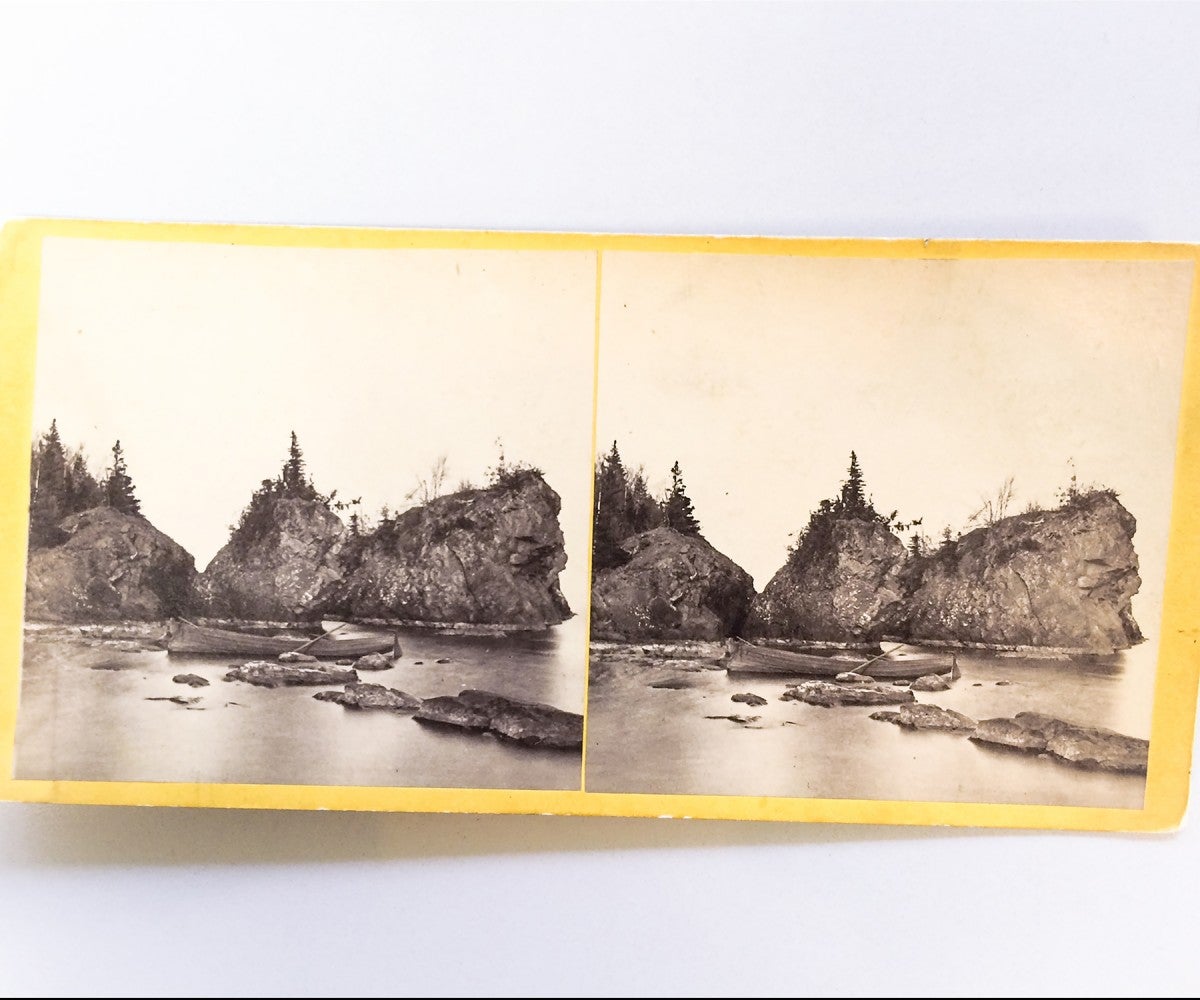

STEREOGRAPHS

In 1868, Albert E. Foote, an assistant in the University of Michigan Chemistry Laboratory, organized a collecting expedition to the Upper Peninsula and Isle Royale. 13 students, faculty, and museum staff accompanied Foote on this five-month trip. The group studied mining facilities, geological formations, flora and fauna. The stereographs, taken by a photographer who accompanied the expedition, document the expedition’s boats and camps, natural sights, the beginning of Michigan mining operations, and Anishinaabe guides. As the most advanced photographic technology at the time, the stereographs were further used in public talks about the expedition, sharing the experience of travel and knowledge gathered with audiences on campus and beyond.

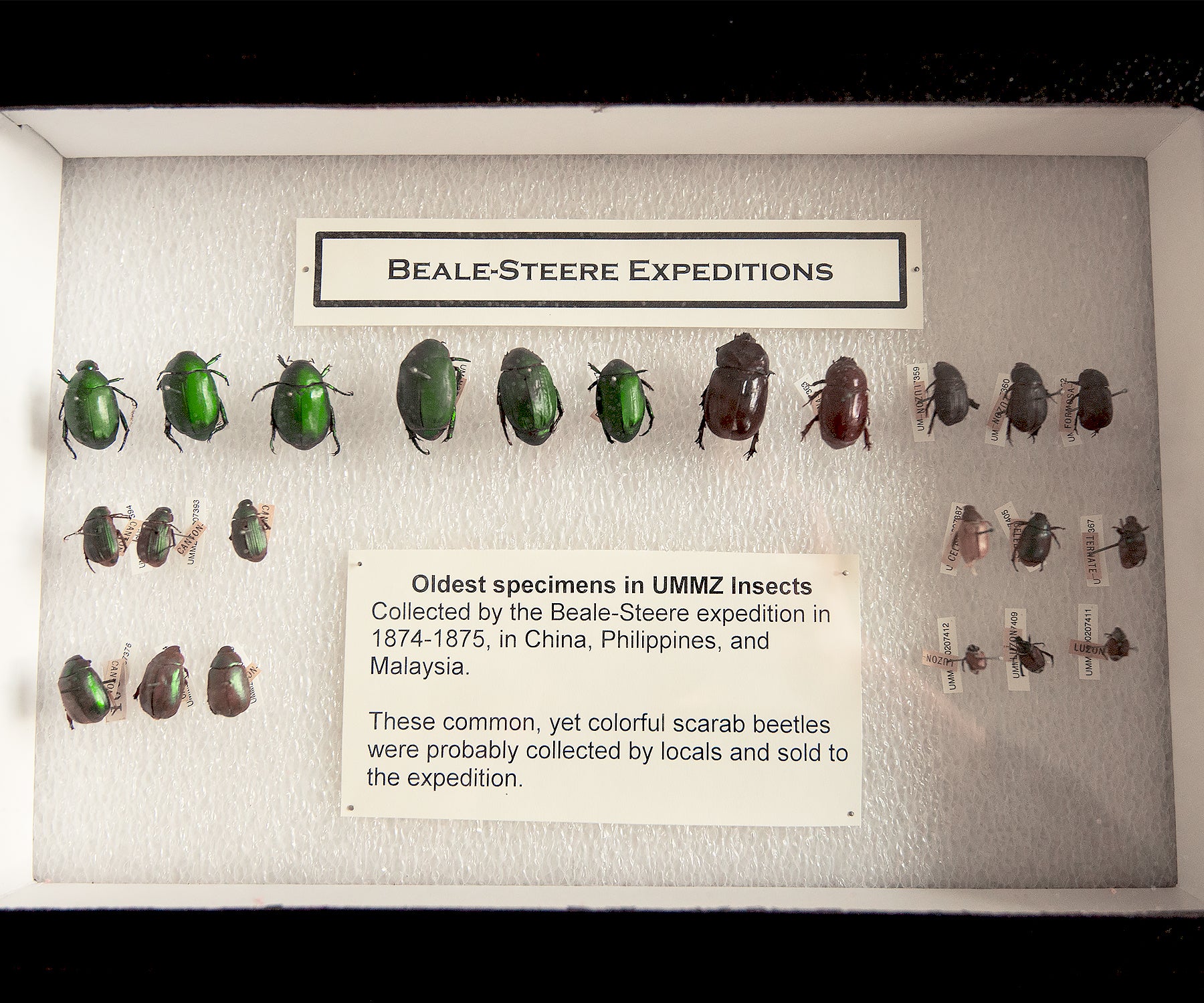

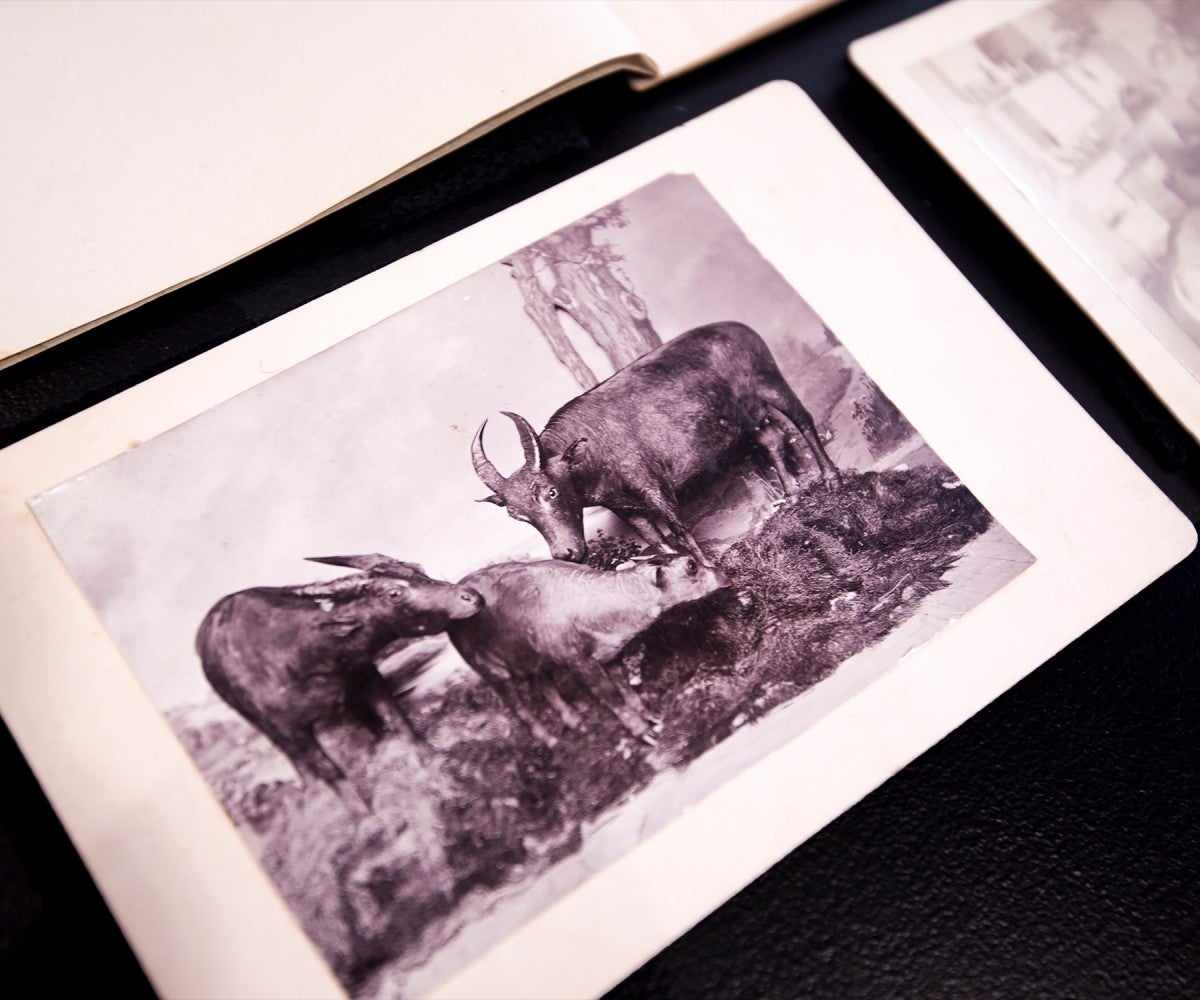

JOSEPH BEAL STEERE

Global collecting for the University Museum began with Joseph Beal Steere’s (1842-1940) world travel in the 1870s. A nineteenth century polymath and naturalist, Steere repeatedly visited South America, the Pacific Islands, and East Asia. The abundance of artifacts and specimens that arrived on campus due to his collecting efforts included sea shells, insects, fishes, fossils, mammal skins, plants, birds (among them over 70 species new to science), pottery, musical instruments, material culture, and notes about indigenous languages. To house these rich collections, the university built a new museum on State Street and appointed Steere as its first head curator. Object Lessons showcases Steere’s historical collecting practices, the breadth of his work, his life and politics. It reunites artifacts and specimens now housed in discipline-specific research collections and exhibits them alongside personal documents from the Bentley Historical Library.

COLLECTIONS & LOSS

In this section, we focus on the loss of collections and museums that once played an integral role in the University’s research and teaching mission. Over the course of the last 200 years, museum and laboratory spaces developed together and are still found in close proximity to one another. As rooms “dedicated to studying,” they echo eighteenth century understandings of the museum as collections of scientific instruments and models, artifacts and objects stored in public display cases, or in the laboratory. While some museum closings were prompted by new openings, other disciplines such as medicine, chemistry or pharmacy moved away from the museum model and closed their collections for good. Registering this loss offers us lessons in the history of science as, among other things, a material history of instruments and practices used in the pursuit of knowledge.

TEACHING MODELS

German glass artisans Leopold and Rudolph Blaschka, famous for their later glass flowers, started their business of scientific models with marine invertebrates in 1862. The fluid forms of living jellyfish, sea anemones, and sea slugs faded when preserved in alcohol but the Blaschkas’ glass models captured their transparent colors and morphological details for study in museums and zoological teaching around the globe. Having been overtaken by other teaching technologies, the models are now artifacts from the history of science and testaments to the splendor of the Blaschkas’ craft.

The paper models showing polyhedra, tetrahedron, cube, and octahedron, on the other hand, are still used in today’s seminars for the teaching of geometry and as visualizations of the formation of crystals. Housed in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, the models were designed by F. L. Krantz Company in the early twentieth century.

ALEXANDER RUTHVEN

Rising from graduate student to professor of zoology, museum curator and director to university president, Alexander Ruthven (1882-1971) left his mark at the University of Michigan. He was trained as a herpetologist, though his research led to new discoveries in biogeography, ecology, and zoology. He served as Michigan’s chief naturalist for the state’s Geological Survey and directed local and global collecting expeditions. A gifted administrator, Ruthven reorganized the natural history collections and expanded its staff. When the University Museum on State Street burst at its seams, he successfully advocated for a new building, designed to bring museum sciences into the 20th century. The new museum opened in 1928 on Geddes Avenue, and in 1968, the regents honored Ruthven’s legacy by renaming it Ruthven Museums Building. As the last exhibition in this very museum before its closing, Object Lessons embeds Ruthven’s work within the larger history of the University’s museum landscape.

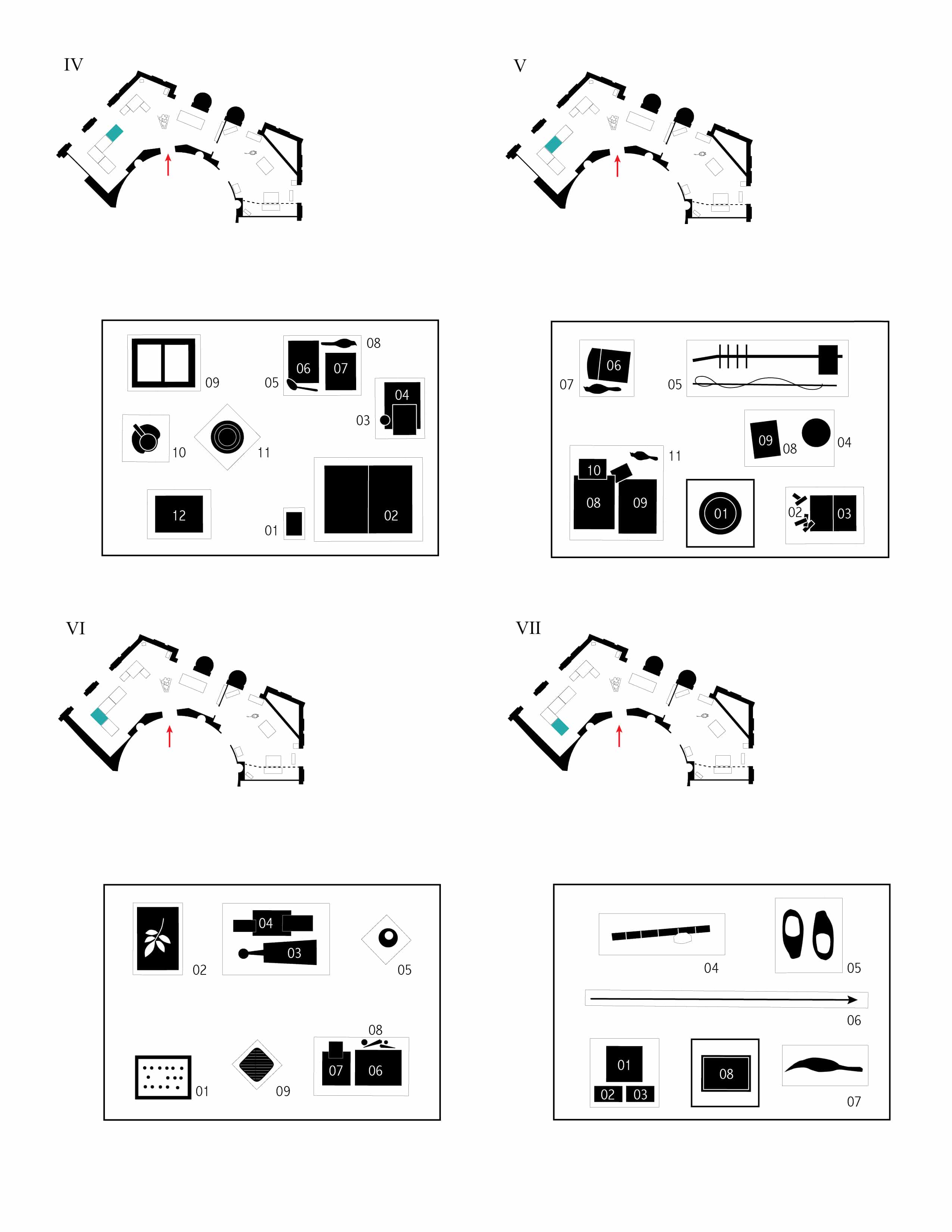

THE CAGE

As we converted the Ruthven’s museum library into a gallery for Object Lessons, the space itself became an exhibit in its own right. We excavated the original floor tiles and utilized the library’s wooden desks, chairs and sideboards, as well as the metal cage for the library’s rare special collection as points of historical reference. Filled with expedition gear, skeletons, delicate bird eggs and taxidermy, the cage evokes the space of a zoological cabinet – allowing us to exhibit precious specimens at a safe remove from the visitors’ touch. Under the spell of the melancholic upward gaze of the antelope heads, the display deliberately estranges these specimens for the visitor. Witnesses of scientific collecting and modeling, the stuffed animals are simultaneously in the visitors’ presence and very far removed from it. The display invites meditations on the relationship between the museum’s function as a storehouse of extinct and dead life forms, the researchers’ efforts to study and protect biodiversity guided by these preserved specimens, and the present exhibition itself, whose aesthetic approach aimed to imbue these forms with new life, to grant them lasting exhibition value.

THE GATES

Placed at the very entrance of Object Lessons, this installation brings masonry fragments from the first University Museum’s facade into conversation with wrought-iron gates designed for the Ruthven Museum’s research wings. The juxtaposition raises questions regarding museum histories, sciences, and their legacies. While the 1881 relief alludes to Darwinian evolutionary theory, the gates to Paleontology from the early 1930s depict a racially charged development of humankind, implying a white supremacist stance: an ape at the bottom, followed by figures supposedly representing a Cro-Magnon, a Neanderthal man, and finally an idealized greek Apollo head as a stand-in for homo sapiens, coded as white. The other panel seen here secured the entrance to the Conchology and Ichthyology collections and shows invertebrate marine life forms set against the leaves of a deep sea plant.

RICHARD BARNES

Richard Barnes’s photographs and installation art interact with the objects on display in the exhibit. The vibrant colors of his large-scale photographs, the gold underneath the set of molds of early Native American artifacts in “Deaccessioned, Reaccessioned” (2017), as well as his object choices contribute centrally to setting Object Lessons’ mood. Consider the still life Richard found in one of the basement storage rooms in the Ruthven Museums building. It shows part of a Fall-themed nature diorama with artificial plant life rendered in realistic manner next to a human skeleton – an object, incidentally, that we could not have brought up into the gallery, given the skeleton’s unknown provenance. Though designed to be life-like, the diorama becomes frozen in time twice over by juxtaposition with the skeleton as a memento mori. And as such, the photograph interacts directly with the displays of dead nature on the tables: it speaks to the ambiguity of the museum object between its unmoored state, severed from its place in natural and human history, and its presence in the exhibit as trace of the past.