Author: Kumool Abbi (abbikumool@gmail.com)

Professor at Punjab University, Chandigarh

The 2022 Punjab assembly elections are till now characterized by a sense of anticipation, uniqueness and hope. As Narayan has pointed out “Every election In India appears as a new text, asking to be read differently, but most times we end up reading them in conventional ways. Social reality and people’s aspirations are changing continuously” (Times Of India Jan. 9, 2022). The forthcoming Punjab elections represent one such new evolving phenomenon with twists and turns at every corner. It is an election taking place in the aftermath of a successful and long drawn out farmers agitation, which has raised hopes and aspirations and “has entrenched a powerful narrative in Punjab against thirty year old mobilization and corporatisation” (India Today Dec. 28, 2021). Moreover, fast developments in “the run up to the Punjab polls like the lynching’s blast and the Prime Ministers Security breach” (The Wire Jan. 11, 2022) are evolving situations which may have the potential to tilt the agenda of the elections. In the backdrop of consistent “mobilizational politics centered around internal conflict and inherent social contradictions” (Times of India Jan. 9, 2022) and Charanjit Singh Channi elevation as the chief minister of Punjab being seen as another “test case for Dalit Politics in India” (Times Of India Jan. 9, 2022).

POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS SINCE THE 2017 ASSEMBLY ELECTIONS

The results of the 2012 Punjab assembly elections have showed that the Akali BJP alliance had “secured 41.9% of the total votes, with Shiromani Akali Dal getting 34.73% of votes and BJP 18% while the Congress Party got 40.09% of the vote share” (Times Of India Jan. 9, 2022). The 2017 Punjab assembly elections were characterized by the emergence of the Aam Aadmi Party on the Punjab Poll Scene. In this election, “the Shiromani Akali Dal-BJP tie up got 30.64% votes of which the Shiromani Akali Dal got 25.24% votes and BJP 5.4% votes” (Times Of India Jan. 9, 2022). The Congress Party, whose vote share had dropped to 38.5%, won the election as the Aam Aadmi Party secured 23.72% of the votes (Times of India Jan. 9, 2022).

The important developments since the last elections which stand out relate to the possibility of “the second coming of an incumbent government (The SAD-BJP notched up this feat in 2012) and a shift from a bipolar contest” (Hindustan Times Dec. 23, 2021) to a “multipolar political structure in 2022” (India Today Dec. 28, 2021). The most significant change that has taken place since the last election is an angst and indifference of the voters giving way to seeking accountability from its leaders, explaining a dramatic shift in electoral politics in Punjab.

The Congress Party having “ousted Amarinder Singh to ward off anti-incumbency and end infighting in the Punjab unit, is now banking on Charanjit Singh Channi, the state’s first Dalit Chief Minister, to turn around the party fortunes” (Hindustan Times Dec. 23, 2021).

The data from the 2011 census has shown that Punjab has 31.9 % SC population which includes 19.4% SC Sikhs,12.4% SC Hindus and 0.98% Buddhist SC’s. Among these communities 26.33% are Mazhabi Sikhs, 20.77% Ravidassia and Ramdasia, 10% Ad Dharmi and 8.6 % Balmiki (Indian Express Sept. 21, 2021) which constitute large numbers and a wide area of influence. Chief Minister Charanjit Singh Channi with less than a few months to govern “has managed to reset the narrative by his common touch, a slew of populist announcements and Dalit consolidation. But the party is still hobbled with internal feuds. Mercurial and ambitious state Congress chief Navjot Singh Sidhu, on the other hand, vouching for his honesty and uprightness insists that he has “a pro-punjab agenda and the right intent to implement it while stating that voters trust him” (The Wire Jan. 11, 2022). He however is “missing no opportunity to take swipes at Channi” (Hindustan Times Dec. 23, 2021 ) which has been magnified with Channi’s selection as the Congress chief ministerial candidate. Clearly the Congress Party is suffering from the adage of “too many cooks spoil the broth” (The Wire Jan. 11, 2022). Though the party leadership is attempting to “take everybody along, including disgruntled senior leaders. It is struggling to get its act together” (Hindustan Times Dec. 23, 2021) and insisting on fighting the elections “under collective leadership” (The Wire Jan. 11, 2022). Interestingly, this is reflected in the composition of the four working presidents it had appointed: Kuljit Singh Nagra (a Jat Sikh), Sangat Singh Gilzian (a Labana), Sukhwinder Singh Danny (a Dalit) and Pawan Goel (a Hindu). The Congress Party was apprehensive that “naming Navjot Sidhu as the chief ministerial candidate may take away the gains the party is believed to have made by declaring Channi as Punjab’s first Dalit Chief Minister.” Since this move is not only seen as a symbolic reaching out but also a showcasing to the Dalits of UP and Uttarakhand, two states that go to the polls as well. Channi’s surprising popularity has given the congress campaign a leg up and slight lead in the campaign despite fighting anti-incumbency.

The Shiromani Akali Dal which has broken its ties with its traditional partner the Bharatiya Janata Party in the feverish pitch of the farmers agitation now faces a “make or break election” (Hindustan Times Dec. 23, 2021). Under the leadership of Sukhbir Singh Badal, in a quest for a “new social coalition” (The Wire Jan. 11, 2022) it has now allied with the Bahujan Samaj Party. This move was seen as a “gambit hinged on the Akalis sway among the Sikhs and Mayawatis appeal among the states 31% scheduled caste vote bank that could well be a game changer in at least 40 seats chiefly in the Doaba belt” (Hindustan Times Dec. 2, 2021). However the “SADs calculations on the Dalit vote” (Hindustan Times Dec. 23, 2021) in an attempted “social engineering” (The Wire Jan. 11, 2022) seems to stands considerably negated after Channi’s surprise choice as Chief minister. Shiromani Akali Dal’s larger issues of apprehension are the ‘blowback of the long simmering sacrilege and drugs issue which had proved to be the nemesis in the 2017 assembly elections and continues to roll the states politics” (Hindustan Times Dec. 2, 2021).

The latest in the cog being the booking of Akali leader Bikram Singh Majithia in the drug racket case on Dec. 21 by the Congress government and the rejection of his bail on Jan. 24, 2022 by the court. Coupled with the impact of the sacrilege episode, successful farmers agitation and breakup of ties with the BJP has made the SAD lose connection with its “key ideological planks: Panth, Peasantry and Panjabiyat” (Hindustan Times Dec. 23, 2021). Yet, the SAD is making an attempt to plunge back into “Sikh Politics” to win back “its core rural vote base that it lost in 2017 polls” (The Wire Jan. 11, 2022). It is simultaneously working to sway Hindu and Dalit votes with promises of making two deputy chief ministers one from the BSP and the other a upper caste Hindu (The Wire Jan 11, 2022). It would also be pertinent to see how the Shiromani Akali Dal fares on its own in an attempt to “reclaim their place as Punjab’s own regional party, like TMC of West Bengal and DMK of Tamil Naidu” (India Today Dec. 28, 2021). The road is arduous as Parminder Singh Dhindsa one of its former leaders explains the prospects for the election “Shiromani Akali Dal to suffer major losses, as they traditionally enjoyed support from rural areas and landlord farmers. People have not forgotten that they were involved in the central government and supported agricultural laws in Parliament” (Outlook Jan. 23, 2022).

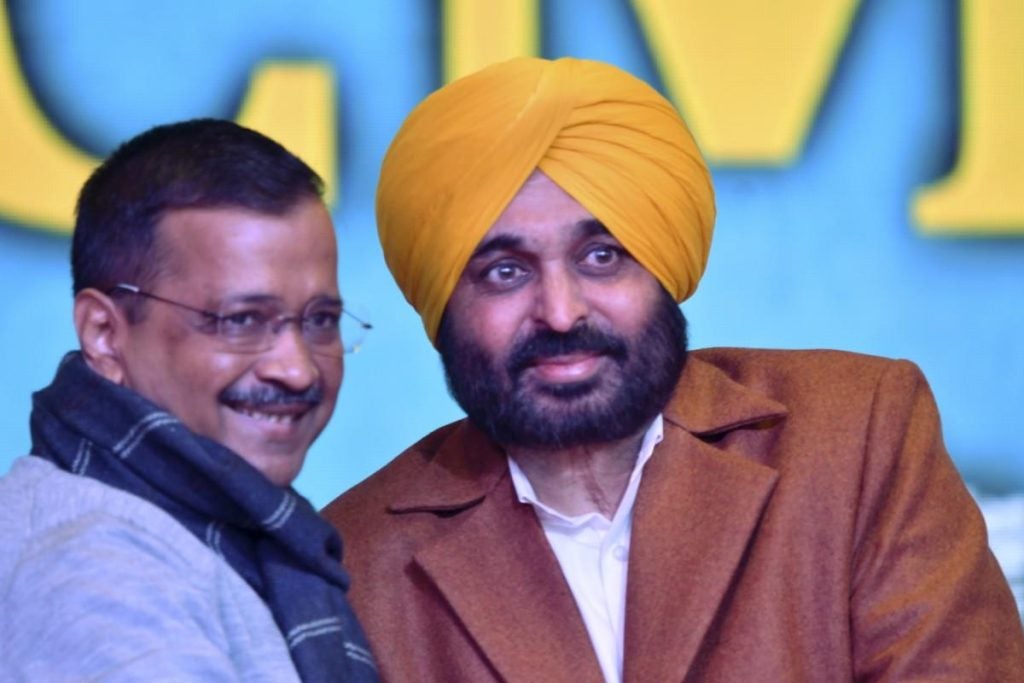

Another significant factor on the electoral scene or the third player is the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) which “despite being rocked by internal bickerings and desertions and a fall in vote share in the Lok Sabha elections to 7.46%, has a sense of resurgence” (Hindustan Times Dec. 23, 2021; The Week Jan. 23, 2022). The party is “blending populism which it has tried successfully with nationalism by taking out tiranga yatras” (The Wire Jan. 11, 2022). The party’s main slogan is “Ik Mauka Kejriwal Nu (Give one chance to Kejriwal).” He has unveiled in a stepwise manner a slew of “Kejriwal’s guarantees,” which involve promises on electricity and water supply, health, education, employment and women’s empowerment. The promises include 300 units of free electricity, free health care for all and Rs 1,000 monthly payment to all women above 18 (The Week Jan. 2, 2022). This campaign being led by Kejriwal himself is based on the belief that “people want to vote for change this time” (The Week Jan. 23, 2022). Sandhu has pointed to a distinction in the approach of AAP during the 2017 and current champaigns: “while in 2017, AAP rode on the Sikh sympathy wave and tried to woo the NRIs, this time its appeal is more nationalistic in character” (The Wire Jan. 11, 2022). However, it is tempered by the lack of a vibrant grass root level organization and a delay in declaring its chief ministerial candidate as well as facing the danger of repeating the same mistake of “overdependence on central leaders” (Hindustan Times Dec. 23, 2021), it suffers from the “absence of strong local leadership and organisational structure in the state.” This becomes a visible eyesore as “Punjab has a very strong regional element, and the perception that the AAP is a Delhi-based party could hurt its chances” (The Week Jan. 23, 2022).

How the AAP tackles clarifications on recent issues which have been raked up like allowing the notification of farm laws in the Delhi assembly, the delay in the release of Devinderpal Singh Bhullar, stand on river waters dispute, the reason for the exodus of many of its leaders is a matter of speculation. Nevertheless, AAP is expected to be the biggest beneficiary of the mood for change among the Punjab electorate.

The fourth player on the scene is the Bharatiya Janata Party and Punjab Lok Congress combining with the support of Sukhdev Singh Dhindsa’s Akali Dal Sanyukt. This alliance is relying on “the saffron parties traditional urban pockets as well as Captain Amarinder Singh’s political experience and ability to attract discounted Congress leaders” (Hindustan Times Dec. 23, 2021). At the same time, the party has resorted to a policy of “political co-opting over confronting” (India Today Jan. 22, 2022). Prime Minister Modi has inducted many Sikh leaders like General JJ Singh, Rana Gurmit Sodhi, DGP Sarbdeep Singh Virk (the Chairman of Punjab Cooperative Bank), Avtar Singh Zira and Harcharan Singh Ranaulte, among others, into the party. He has also attempted to reach out to the Sikhs by important overtures: announcing repeal of farm laws on Gurpurab, reopening of the Kartarpur corridor and declaration of Dec. 26 as Veer Bal Diwas in memory of Guru Gobind Singh’s sons” (The Wire Jan 11, 2022).

Measures which as described by BJP minister Hardip Singh Puri is a “battle for the Sikhs heart and mind, the Sikh psyche, I think that thing is on” (India Today Jan. 22, 2022). More than anything else this alliance “has the potential to upset the electoral calculus of other players” and “muddying the waters” (The Hindustan Times Dec. 23, 2021). This alliance has the potential to “dent” the Akalis, Congress and the AAP depending on the vote share. The BJP is “hopeful that its urban base could tilt since multiple claimants for rural electorate could make the victory margin narrower” (New Indian Express Dec. 31, 2022). A senior party functionary explained this point in detail: “Other than the BJP led front, there are at least three strong contenders for the rural vote base. It’s given that the rural vote will split majorly, and this will give an edge to the BJP. That is indeed adding glue to the party to attract sitting MLAs and former legislatures” (New Indian Express Dec. 31, 2022).

The fifth players who have recently entered the arena are the twenty-two farmers unions who spearheaded the year-long agricultural successful protest against the farm bills, such as Sanyukt Samaj Morcha. While “transforming itself into a political group” the morcha avoided the word ‘party’ in its “political nomenclature” instead, making an “attempt to preserve the character of the movement where it stemmed off” (India Today Dec. 28, 2021). The morcha also continues with it “the hallmark of left of Centre Regional politics” which will be seen as “a new experiment in regional politics” and has also requested being allotted the tractor as a symbol for their party. The Sanyukt Samaj morcha plans to contest all the 117 assembly elections in the state with the exception of ten seats for Gurnam Singh Chaduni’s Sanyukt Sangharsh Party, an agreement which has recently been notched up.

Balbir Singh Rajewal, the president of the Bharatiya Kisan Union (BKU), will head the new group. He said Punjab was facing a lot of problems such as drugs, unemployment and migration of the youth from the state and they wanted to address them. “We will be fighting all the 117 assembly seats,” to enable a “political change” (Business Standard Dec. 25, 2021). Another farm leader Harmeet Singh Kadian claimed that there was public pressure to take the political plunge. “The people asked us to do something so we decided to form this morcha,” he said (New Indian Express Dec. 26, 2021). The main goal being “the betterment of Punjab” (Business Standard Dec. 25, 2021) and to bring “a new dawn” (Business Standard). Similarly, for farm leader Baldev Singh, “farm leaders are entering politics keeping in mind the expectations of the people.” He hoped to “give a new direction to Punjab” (Business Standard Dec. 26, 2021). He further clarified, “we assure the people of Punjab that they repose faith in us and we will work towards resolving their issues like curbing drug menace and stopping youth from going abroad” (Business Standard Dec. 26, 2021). However, the novel way in which the elections are being played out in the Punjab express a clear mood of disillusionment with traditional parties, anticipation, restlessness and hope amidst a heightened political consciousness. The continuous movement of politicians across parties in opportunistic tie-ups is creating many carnivalesque moments in a five cornered contest. Sanjay Kumar of the CSDS puts it “in this messy situation there will be a desire for change i.e. kuch to badlav aana chahiye” (there should be some change) (News 18, Dec. 26, 2021).