Past Studies

Children, Money, and Market Exchange

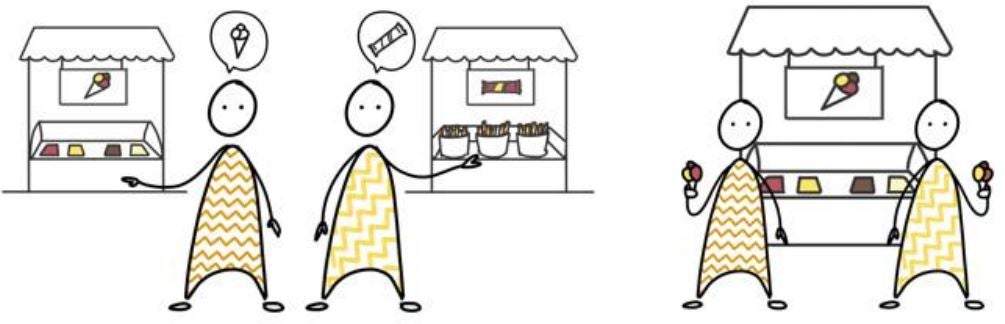

Children, like adults, often have to make decisions on how to distribute items. In some cases, children may opt to distribute items equally, appealing to equality norms. In others, children may opt to distribute based on need, appealing to equity norms. In this study, we investigated whether children appeal to a different (but related) type of norm—market norms—when deciding how to distribute items. That is, will children distribute based on willingness to pay? Read More We asked children 5-10 years to help a Giver decide how to distribute extra stickers and found that children as young as 5-6-year favor friends willing to pay more for stickers. We also found that market norms influenced older children more than younger children as evidenced by the increasing difference in the number of stickers distributed to friends offering more vs. less as children aged. Overall, results show that even young children consider market norms when deciding how to distribute items, and that appeals to market norms increase with age. We plan to explore children’s use of market norms in future studies.

Children, like adults, often have to make decisions on how to distribute items. In some cases, children may opt to distribute items equally, appealing to equality norms. In others, children may opt to distribute based on need, appealing to equity norms. In this study, we investigated whether children appeal to a different (but related) type of norm—market norms—when deciding how to distribute items. That is, will children distribute based on willingness to pay? Read More We asked children 5-10 years to help a Giver decide how to distribute extra stickers and found that children as young as 5-6-year favor friends willing to pay more for stickers. We also found that market norms influenced older children more than younger children as evidenced by the increasing difference in the number of stickers distributed to friends offering more vs. less as children aged. Overall, results show that even young children consider market norms when deciding how to distribute items, and that appeals to market norms increase with age. We plan to explore children’s use of market norms in future studies.

Research by Margaret Echelbarger

Do children think that race can change?

Most adults believe that race is stable (the race you have as a child is the race you will have as an adult). In these studies, we questioned whether children also believed that race was stable, or whether this concept was learned over time. We found that White 9- to 10-year-olds believed that race was stable, whereas White 5- to 6-year-olds did not. Interestingly, Black 5- to 6-year-olds, like older White children (but unlike same-aged White children), believed that race was stable. These findings suggest that the belief that race is stable develops with age, and at different rates across racial groups.

Daily Mail Article | Publication

Research by Steven O Roberts

Who’s the Boss?

How do children figure out who is in charge in different social settings (e.g., at home, in school, at a town hall meeting)? Are children able to pick up on subtle cues similarly to adults? In a series of studies that we conducted at the Living Lab, we presented children (ages 3 to 9) with illustrated stories describing a situation where one character had more power than the other character. For example, in one of the stories, two characters arrived at a sandbox and saw one toy that they both wanted to play with, but only one of them got to play with the toy. After each short story, we asked children who they thought was in charge, and why. Read MoreWe found that even our youngest age group of children (3- to 4-year-olds) easily identified characters who were in charge in situations where the character got more resources than the other, where the character got what they wanted over what the other character wanted, and when the character in charge was the one denying the other one permission. However, only around 7 to 9 years of age did children begin to show adult-like understanding of who is in charge in other more subtle situations, like when one character was setting trends for others to follow, or when one character was giving orders to the other character. This shows that younger children, even if they are given orders to clean their room or finish an activity by a teacher or parent, they may not know this means the adult giving orders is in charge!

How do children figure out who is in charge in different social settings (e.g., at home, in school, at a town hall meeting)? Are children able to pick up on subtle cues similarly to adults? In a series of studies that we conducted at the Living Lab, we presented children (ages 3 to 9) with illustrated stories describing a situation where one character had more power than the other character. For example, in one of the stories, two characters arrived at a sandbox and saw one toy that they both wanted to play with, but only one of them got to play with the toy. After each short story, we asked children who they thought was in charge, and why. Read MoreWe found that even our youngest age group of children (3- to 4-year-olds) easily identified characters who were in charge in situations where the character got more resources than the other, where the character got what they wanted over what the other character wanted, and when the character in charge was the one denying the other one permission. However, only around 7 to 9 years of age did children begin to show adult-like understanding of who is in charge in other more subtle situations, like when one character was setting trends for others to follow, or when one character was giving orders to the other character. This shows that younger children, even if they are given orders to clean their room or finish an activity by a teacher or parent, they may not know this means the adult giving orders is in charge!

Publication

Research by Selin Gülgöz

Children’s Beliefs about Race and Inheritance of Traits

We were interested in knowing whether children believe that people inherit certain traits through their racial background. For example, some people might think Black people or White people are naturally good or bad at certain things because of their race. This may lead to negative consequences such as racial stereotyping. In order to better understand this, we asked 80 Black and White children ages 4 to 12 whether children who were adopted by cross-race parents would inherit the traits of their biological parents (same-race parents) or adoptive parents (cross-race parents).Read More We found that 4-6-year-old Black participants believed White kids would be more like their biological parents than Black kids, and 10-12-year-old Black participants believed Black kids would be more like their biological parents than White kids. We didn’t find any age differences or kid race differences in White participants’ responses. These results indicate that Black children may see race as important for the traits that individuals inherit. This may be because race is a more relevant aspect of their lives as racial minorities. Given our small sample size, these results are preliminary and more data is needed to confirm these findings.

Research by Amber Williams

Understanding the Power of Thought

How do children and adults conceptualize the power of the mind? Parents may instruct their children to make a wish before blowing out their birthday candles or to pray before bedtime. We examine what children believe about these and other forms of mental activity. Children ages 3- to 11-years were read about a protagonist who desired for something to be achieved, and either wished or prayed for their desire to be fulfilled. Some of the desired outcomes could plausibly happen with ordinary human intervention (e.g., keeping a bowl from sliding off a table during an earthquake) and other outcomes were impossible, even with human intervention (e.g., keeping a crumbling, tilting building from falling during an earthquake). With increasing age, children increasingly reported that both plausible and impossible desires would not be fulfilled; and across the age range children reported that desires for impossible outcomes would be fulfilled less often than desires for plausible outcomes. Children’s judgments that wishes vs. prayers would be fulfilled were comparable, but did vary based on participants’ personal experiences with praying.

Research by Jonathan Lane

How does language compete?

Bilingualism is a typical experience, yet relatively little is known about its impact on children’s cognitive and language abilities. Bilinguals must continuously select the correct words for each language. We presented kids with competing words as they selected the image that matched one of them (ex: car, cat) and found that it took them longer than those that did not compete (ex: car, dog). Read MoreThe results helped us develop a task that we are now using for a neuroimaging study comparing bilinguals and monolinguals as they select words that compete in English.

Research by Maria Arredondo

Lessons Learned

How do children make meaning from negative experiences? To examine this question, we read children short stories that described everyday conflicts. Children were then asked to reflect on either the emotions the character felt in the story, or what lessons the character could learn from it. Children’s responses revealed that they were able to derive more meaning from the story when asked to discuss what lessons the character could learn. Read More Specifically, when discussing “lessons learned” children were more likely to use language that generalized the character’s experience beyond the here and now, demonstrating that they were framing the conflict within a broader context. This study sheds light on how children use language to make meaning from negative experiences.

Research by Ariana Orvell

Children’s everyday language use

How do children distinguish between norms–which apply to everyone, and preferences–which are specific to individuals? In our study, we found that children’s ability to differentiate between norms and preferences is built into their interpretation and use of language. Children as young as three years old were sensitive to subtle cues that signaled that a question referred to norms (e.g. “What do you do with books?”) versus preferences (e.g. “What do you like to do with books?”) as evidenced by their responses. Read MoreThis study sheds light on how children learn about norms and rules of behavior in their social world.

Publication

Research by Ariana Orvell

How does language impact memory?

This study investigated whether the type of language used can help and/or hinder children’s memory for facts. Sometimes we use certain words to refer to particular objects, animals or individuals; for example, “These goats have horns and like to eat grass.” But other times we use language to refer to them in a general manner, also knows as generic sentences; for example, “Goats have horns and like to eat grass.” We found that children remember more information when generic sentences are provided.

Research by Maria Arredondo

Children’s Understanding of their Future Selves

For children to achieve many of their future goals (e.g. going to college), they must take action now (e.g. doing their homework). To motivate children to take that necessary action requires that they understand that their current (“me now”) and future (“grown up me”) selves are connected. In our study, we had children consider their current and future selves as either connected or separated and assessed the effects of those ways of thinking on their behavior. We found that for children as young as 4th grade, having them think about the future as connected rather than separated increased their willingness to delay gratification – to sacrifice smaller immediate gains for larger, long-term gains.

Research by Neil Lewis, Jr

Children’s Thinking about Fair Reward and Punishment

Previous research shows that even when young children know that some people are more deserving of rewards compared to others, they still often prefer to hang out reward equally if given a chance. Older children, like adults, tend to give more reward to those who are most deserving. This study, we asked the same type of questions, but asked how children would fairly distribute punishment, and found that this age difference was the same. In hypothetical scenarios, when one person did more of a bad thing than the other, the preschool-age participants often gave two negative consequences to each of the characters (an equal allocation). Read MoreIn contrast, the older children and adults preferred to allocate their punishments equitably, where a person who does more bad gets more punishment. This study demonstrates that there is a developmental shift toward a preference for allocating discipline based on deservingness—and away from a consistent preference for equal allocation.

News Article | Publication

Research by Craig Smith

Do Children’s Feelings about Spending Money Predict Their Financial Behavior?

In studies of adults, “tightwads” find spending money painful and “spendthrifts” do not find spending painful enough. These differences predict a variety of important financial behaviors and outcomes. In this study we asked if similar feelings about spending could be measured in 5-to- 10-year-old children. Using a special type of interview, we found that children are indeed able to report on their emotional responses to spending and saving, and these responses were related to parent reports of children’s financial behavior.Read More Children’s emotional responses to spending were also predictive of whether they chose to save or spend money in a little ‘store’ we established in the lab area. Therefore, positive and negative feelings about spending emerge early in life, and are useful predictors of how children make decisions about what to do with their money.

Research by Craig Smith and Margaret Echelbarger

More StudiesTransplants

This study explores the extent to which children believe that the causes for personal characteristics (e.g., goodness, badness) reside within an individual. Do children believe that trading hearts with fictional characters (both human and non-human) will result in them ending up more like the character? Read More Children are told about a series of characters, and after the characters are introduced, children are asked to imagine that they trade either hearts or dollars with the character. They are then asked to report whether they would likely take on attributes of the character or stay the same. We predict that all age groups will predict more characteristic change when asked about a heart vs. a dollar exchange. Parents are encouraged to further inquire as to where their children think traits like intelligence or kindness come from, which may lead to discussions of the importance of self-motivated actions vs. simply assuming that these traits are fixed.

Children’s Views on States and Traits

Young children know that certain categories are stable across time. For instance, they reason that a boy will grow up to be a man, and that an English-speaking child will grow-up to be an English-speaking adult. What do children think about the stability of emotions and race? Do they think that one is more stable than the other? In this brief study, children are shown images of children and adults with different emotional expressions and skin colors. Children are asked to show which adult each child will grow up to be; they have the option of matching on the basis of emotion or race. We expect that older children will be more likely to match on the basis of race. This study will add to our knowledge of how children reason about the people around them.

Research by Steven Roberts

Reasoning about conformity

In this study, we introduce children to fictional groups called Hibbles and Glerks. Hibbles typically behave one kind of way (e.g., eat Hibble berries) and Glerks typically behave a different way (e.g., eat Glerk berries). What do children think about Hibbles who, for instance, eat Glerk berries? More broadly, this study examines children’s beliefs about group conformity. Is it OK to go against one’s group? Or should we all conform?

Research by Steven Roberts

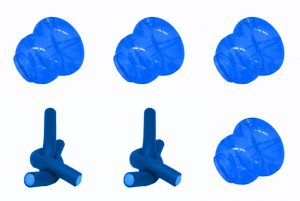

Children’s Understanding of Scarcity

Children, like adults, make a large number of decisions each day, and many of these decisions are affected in some way by concerns over scarcity. We know that scarcity can play a role in adults’ decision-making, but much less is known about the role it can play in children’s decision-making. For example, do children view scarce items as more desirable? Do children think that scarce items are worth more than non-scarce items? Finally, what factors affect the choices that children make with respect to scarce items? In a brief, single-visit study, children between the ages of 3 and 12 years are asked to make some choices for different recipients, including themselves. Children are then asked to explain some of the choices that they made. Parents are also asked to complete a short questionnaire about their child.

Children, like adults, make a large number of decisions each day, and many of these decisions are affected in some way by concerns over scarcity. We know that scarcity can play a role in adults’ decision-making, but much less is known about the role it can play in children’s decision-making. For example, do children view scarce items as more desirable? Do children think that scarce items are worth more than non-scarce items? Finally, what factors affect the choices that children make with respect to scarce items? In a brief, single-visit study, children between the ages of 3 and 12 years are asked to make some choices for different recipients, including themselves. Children are then asked to explain some of the choices that they made. Parents are also asked to complete a short questionnaire about their child.

Research by Margaret Echelbarger

More StudiesVariety seeking in children

In recent work conducted through the UM Living Lab, we learned that children prefer varied sets (sets with different items) to non-varied sets (sets with the same items). In this current study, we are interested in whether children’s selection of varied sets can be influenced by subtle contextual cues. We ask children 4-9 years to complete a short activity and then select items from a larger set. If this seems vague, that’s because it is! We’re interested in whether the activity influences the selections, even though they are seemingly unrelated. This study is currently underway and we’re excited to share the results with you when they are available!

Research by Margaret Echelbarger

Who’s the Boss?

You’ve probably experienced power struggles with your kids at times, or at least observed them in situations where there was a power imbalance. For example, you may have noticed that sometimes in kids’ group play, there are those children who lead the group and set the rules for the game, and those who follow the leaders. Such play situations are not all that different from the way in which adults experience power in their everyday social interactions. In fact, children may learn in these early experiences the different ways in which people may become powerful, and how power differences affect social roles and relationships. However, power is a complex concept that involves multiple facets, like the ability to access and control resources (wealth) and the ability to achieve goals. Read More

You’ve probably experienced power struggles with your kids at times, or at least observed them in situations where there was a power imbalance. For example, you may have noticed that sometimes in kids’ group play, there are those children who lead the group and set the rules for the game, and those who follow the leaders. Such play situations are not all that different from the way in which adults experience power in their everyday social interactions. In fact, children may learn in these early experiences the different ways in which people may become powerful, and how power differences affect social roles and relationships. However, power is a complex concept that involves multiple facets, like the ability to access and control resources (wealth) and the ability to achieve goals. Read More

We have been exploring this question in a series of ongoing studies. In our studies, we tell kids fun, illustrated stories and ask them to decide who is in charge and why. So far, we have been finding that even the youngest kids (3-4 years) have clear concepts of what makes a person powerful, although their reasoning about social power does not become adult-like until around 7 to 9 years of age. For example, younger children are very good at judging who is powerful in a situation where one character in the story gets more candy than the other. However, the same group of kids are not that good at understanding who is more powerful in situations where one character is giving orders to another character to clean up, or where one character is dictating what another character should wear. Our study is important in that it shows that social power may not be a unitary concept, and that children may understand different parts of it at different points in development.

What Will You Want Tomorrow?

Our current states can interfere with our forecasts about what we will want or feel in the future. Adults who shop for groceries on a full stomach tend to buy less compared to adults who haven’t just eaten. In this study we explored whether children would be open to the input of a parent when making a prediction about what they would want in the future. We first established that children prefer pretzels over water for a snack. We then made some children thirsty, and found that these children predicted that they would want water the next day for a snack, instead of pretzels. Read MoreThis is a type of forecasting error known as the ‘presentism bias,’ in which a current desire influences thinking about what one will want farther into the future. Some children heard their parents say, “I think you’ll want pretzels tomorrow,” but this parental input did not improve children’s desire forecasts; most children still anticipated wanting water over pretzels for a snack. Other children heard parents address the nature of the forecasting error: “You’ll have water soon, so I think you’ll want pretzels tomorrow.” This input, which explicitly addressed something children were forgetting, led children to make more accurate predictions of their future desires. Therefore, parents can help their children think more accurately about their own future mental states, but overly simple input from parents isn’t as helpful as input that addresses biases in children’s thinking about their future selves.

Research by Craig Smith

What do children understand about villains?

Many children are drawn to shows and movies that involve clashes between villains and heroes. Some children also experience real-life bullies in their day-to-day lives. Yet there has been little systematic study of what children understand about the nature of villains and wickedness, and how this understanding develops over childhood. We explored this question by interviewing 3-to-12-year-old children about villains and heroes.Read More

While we’re excited by our results so far, our research continues as we try to discover where children think these mean/villainous traits come from. Are they learned, or are they present at birth and hard to change? We hope this line of research sheds helpful light on how children make sense of some of the types of people and behaviors we all encounter in the social world.

Research by Craig Smith

More Studies

Children’s Understanding of Personality Traits

Understanding other people is important in our daily lives. When we understand that the way people act can tell us about what they are like, we are better able to anticipate the responses of others and adjust our interactions with them accordingly. Young children sometimes struggle making this connection between actions, personality traits, and future behaviors. Read More We, at the Living Lab, want to know if the way we describe the actions of people might influence how well young children understand these people and anticipate their future actions. We hope our research can improve our understanding of how to communicate with children about people, personality, and behavior.

Research by Preeti Samudra

Responses to Academic Setbacks

A recent study based on national data indicates that the ways parents respond to their children’s grades have implications for their children’s long-term academic achievement. However, it is unclear why parents choose to respond in certain ways, and how children feel about their parents’ responses their school performance. This study explores these questions with children and their parents using a combination of survey questions, vignettes, and a joint parent-child activity. The goal of this study is to understand why parents respond to academic setbacks in various ways and to compare those responses to how children believe parents should react to academic setbacks.

Research by Sandra Tang

How do children think about words?

As children begin to read, they learn to connect arbitrary symbols on a page (print) with sound and with meaning. How do children make these connections? How do they reason about the ways in which words are similar or different? By asking children to think about the sounds and meanings of words, we hope to learn more about how children develop these skills that are critical to becoming a successful reader.

Research by Rebecca Marks