The Plaque

My dad wanted a lot of things that didn’t happen.

One was to be with me more than every other weekend,

Another was to be a history teacher.

So, one dawn, we started a cross-country trek to Civil War battlegrounds–

The longest unbroken time we’d ever spent together–

Hurtling toward the horizon of what we thought we knew,

To try to make up for all these things that weren’t.

The Audio Tour

In the time of

The cloud of dust and then delayed crumble of falling statues,

I heard the music of a country built:

From the rifles propped on porches in rural Alabama,

To the wind whipping boarded windows of hospitals in the Ninth Ward

Testifying New Orleans was still drowning,

To the thrumming, leaning weight of South Carolina phantoms

That made me clutch my Buddha necklace

And whisper prayers and apologies into my hands.

The South peeled fingers back from mouths of fear I’d inherited

In concert with other voices, amplified.

Driving into Tennessee,

for all its twang and strum from Black roots that my dad tried to teach me,

He laughed and turned down

The Nah and Nam and Suboi and Ruby Ibarra dipthonging through my speakers,

So it was just the whir of tires on the tree-lined rolling highways,

And the gravel crunching as I pulled up to the Carnton Plantation

At the Battle of Franklin.

“Nothing,” preached a voice to a bermuda-shorted,

Camera-toting pale family

“to do with the blacks.

The Civil War was,” he

Claimed, “solely economic.”

The family nodded,

As my grip tightened on my entry ticket,

Dampening from my palms beaded with sweat like a salted avocado.

I remembered all the Black hands that served White hands,

My hands,

Across counters in every state that I’d crossed

To get here.

The tour guide was a graduate student

And breathed adjectives of awe.

“The benevolent Madame McGavock,” she gushed,

“Generously opened her home

to hundreds of wounded Confederate soldiers.

Singlehandedly,” she claimed, “Lady McGavock

Tended to the war heroes.

She was,” the student guide paused dramatically,

“The last angelic face they saw.”

The mathematics should be easy.

How could one lady do all of that?

I looked to my dad, but he was lost in details

Again, not seeing me but staring at some pattern

In the ceiling.

In my head I could hear Kendrick echoing

Through that singular sound of being lied to,

The thrum of blood to my ears:

“What they see from me

Would trickle down generations in time

What they hear from me

Would make ’em highlight my simplest lines.”

So I asked, “What about the slaves?”

All eyes on me,

The tour guide stumbled into,

“She gave them the night off.

She was friends with her

Servants.”

Others on the tour liked this answer,

Nodding and smiling.

“Friends,”

I repeat.

“So you expect us to believe one white lady did all the dirty work of nursing and saving, while a

plantation full of enslaved people had the night off thanks to their ‘friend’?”

The student

Furrowed her brow.

“Mm hmm. That’s right.”

My dad raises his hand only waist high

To quell my anger.

“Be nice,” he’d always cautioned me.

It only made me angrier.

It had always been my mother who was able to silence me–

Her chained palms and arthritic knuckles and sideways leers,

Pain-seeded eyes that reminded me of the precariousness of my difference,

Of the danger of speaking out, of trying too hard to be visible.

“Mỹ đen” she’d always codeswitch because she knew that much about the American tongue that made ‘Black’ a bad word, “have too many problems. We have enough of our own. And your dad,” she sucked her teeth here and switched to English again, “he white so you white so more easy for you.” She paused, maybe reading my face, and decided, “You have no problems. Stop whining.”

“So, gradually, she pressed her teeth together

and learned to hush” (Hurston 71).

My dad clasped his hands behind his back

As the tour guide quickly redirected us into the next room.

A mustached man murmured something

In his companion’s ear.

All I caught was “Obama” and “taxes,”

Then a muffled guffaw,

But no one on the tour looked at me after that.

They followed a student.

And then I did too.

The Gallery

I’d gotten into college by accident, as sometimes family firsts are. By the time I figured out how to get to freshman orientation, all of the English classes were full, so the counselor, taking each of us in the long line by number rather than name, enrolled me in Black Studies 100. “It’ll be the same,” he lied.

If my mother had asked about school, I wouldn’t have told her. “Stay away,” she always told me about Black people, her gums purpling where they met false teeth. When my dad asked, “What’s Black Studies?” I didn’t know how to answer. Of many confessions, one is that I didn’t want me to take Black Studies either. Because I had not yet learned how inextricably tied our histories were. I had yet to see as subject and object.

At the college bookstore, I found the assigned textbook: Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God. My dad waited in line with me and paid for all of my books, and all of the ones that would be assigned in my following semesters of what became of a string of three degrees. It was just as he’d done with all my childhood books, series after series of chapterbooks that kept me out of trouble. His twelve dollars gifted me a paradigm-shifter, one of my most worn spines. Yet, the markings in it are only from that first semester of college–light, timid pencil underlines of Hurston’s words that reverberate to my core still today. I’d worried that the consistency attested to lack of growth, of learning, but I learned at Carnton and in the Black Lives Matter protests in the years thereafter, that it was truth.

“Janie full of that oldest human longing

—self-revelation” (7).

I’ve held on to all the papers from that Black Studies course, keeping the trail that singed and curled away from the burning fingertips of those who came before us:

On the first day of class, Professor Fuller lined us up. Chalk dusted the back of my sweater

as I tried to lean out of everyone’s view. Depending on our answers to her questions, we would take a step forward or backward.

“Did you grow up in a house?”

“With two parents?”

“Does your mother have a college degree?”

“Take a step for every generation you can trace back on your family tree.”

“Does anyone in your family have a criminal record?”

Questions later, I remained with my fingertips on the chalk shelf, Chantal next to me but looking straight ahead at our classmates standing in a bar graph of privilege.

“‘us colored folks is branches without roots

and that makes things come round in queer ways’” (16).

I wanted to drop the class after that exercise. But I didn’t know you could do that. And then she kept me by writing to me.

To iron out those inequities, to show how it can be, and was, all taken away, our professor put us on the line. “Like the slaves,” she told us, “you will be brothers and sisters bound by sweat and blood. You will be responsible for each other’s failures and be punished together.” That day, in our new family, we wrote, in repetition:

The first email I ever received, which sounds like history now, Chantal wrote. She scheduled study times; “I’m not gonna let you drag me down,” she wrote to all of us. Equally selfish and hopeful, I felt as if she were writing only to me. Bound by words, we huddled in the must of books trying to do different.

Chantal never returned my gaze. I began to worry that she thought I was studying her, fetishizing her. Maybe it was one of the many things I didn’t know I could do. She befriended a bubbly white girl who asked her pointed questions about what it was like to be Black, and the other Asian girl in class who wore tank tops and glittery eyeshadow. I didn’t know anything about them, but I was jealous that Chantal had let them into her circle and not me. The closest I got to her was when I began dating one of our classmates, an Afro-Latino who everyone liked and whose virginity I was afraid to take. I didn’t break up with him because I didn’t know I could do that. I watched as she cornrowed and beaded his hair that clicked as he told our professor we were together “Like peas and carrots.” She smiled her “y’all” over her shoulder, wet curls swinging and thrushing over that booty that other boys in class bumped fists over.

Knee to knee in her closet office I told her she–the most educated person I’d then ever spoken to–made me want to be a writer, made me remember the journals packed away where my mother wouldn’t find them. “Maybe,” she said, “it’s the Native American in me. Or maybe it’s my roots to Africa.” Her wrists curtained her hair behind her shoulders, and the light shone on her freckled nose. “But I think it’s important to go back to what makes us.” And, up until she said those words to me, I didn’t know you could do that either.

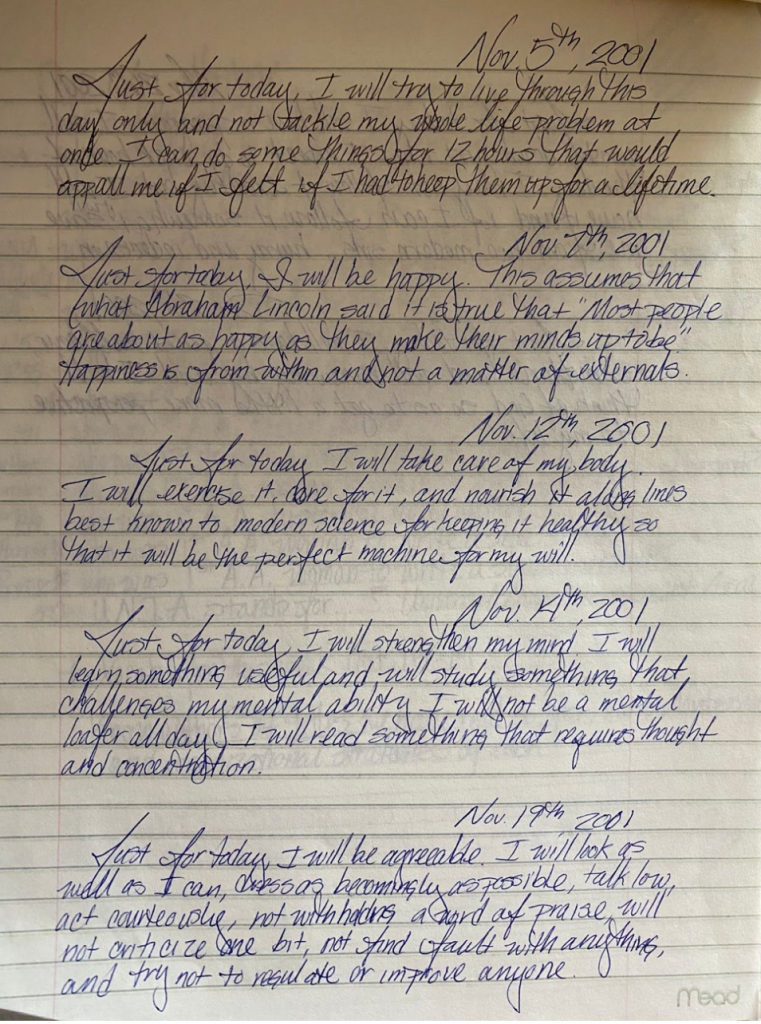

For weeks, she helped us survive the line in a series of recitations that began “Just for today”:

Newspapers came. Journalists scribbled on notepads, which feels like history now, and camera apertures zoomed and clicked her at that chalkboard that had dusted my hands, recorded the sythm of her words that went around and straight through me. They interviewed Chantal, our leader, and she cried. And I was envious.

“‘Us colored folks is too envious of one ‘nother.

Dat’s how come us don’t git no further than us do.

[…] Us keeps our own selves down.’” (39)

It’s sense now that my first essay was about running: a mother and daughter bound by pain and survival, a father and daughter trying to fall in step, a history interrupted–the inertia of restless legs pounding the earth.

Among her piles of plastic bags of prescription bottles and perfume and nail polish, my bà ngoại would lay on our couch, just visiting, like she was always temporary, an arm draped across her forehead, her dagger-toenailed feet planted flat, knees swaying back and forth to the rhythm of hummed prayer, moving, moving all through the night, her body still on Viet Nam time.

They say that I sleep like her. Ready to run.

My kindergarten teacher mocked

My running around the sockball diamond

Squinting into the sun,

I ran over classmates’ shadows shivering with laughter.

I imagined running wild and free like freckled Laura in Little House,

To and away,

I ran away from Vietnameseness and Whiteness,

And then aimlessly while shuttling on couches,

Unable to decide where to go,

And fast, strong and tanned calves,

From white vans that pulled up alongside the Oceanside pier

Where I learned to live alone at the shore, that restless ecotone.

Dad ran marathons

And I could feel disappointment hollow

My ears in absence of a medal’s ting.

The running I did was inside,

No numbers, no awards.

The only time she saw it,

My mom told me, only once,

“You my wild horse. Always running.”

“She had an inside and an outside now

and suddenly she knew how not

to mix them” (72).

For our final exam, we shared a meal. I learned that mac and cheese didn’t come from a box.

I listened to the girls in the class cry for their brothers in gangs. Everyone but me told stories of our grandmothers who passed down food and story. Chantal never looked at me, and I’ve since regretted taking it personally, of letting it be my swelling silence.

“The stillness

was the sleep

of swords” (81).

Chantal hugged and cried into the hair of our professor. As I witnessed their moment of closeness, I filled with the knowledge that I had learned more than I could show, that I couldn’t. But I’d also erred in waiting for belonging to come to me, in longing for something that wasn’t mine because I was just beginning to learn how to see myself.

I failed all of my other classes that semester. But never did again, trying to make up for the things that weren’t.

“She had found a jewel down inside herself

and she had wanted to walk where people could see her

and gleam it around” (90).

The Gift Shop

Bloodstains rorschached the upstairs hardwood.

The student mimicked

Surgeons’ frantic tossing of amputated

Limbs into the corner nearest a window.

I retreat from the circle and stand in the middle

Of the brown amoeba of old blood.

Out the window,

Imagining the body parts

Gathered by people reduced to the same.

It had taken me this long to say something

And here I was still standing at the periphery of the one story.

Rib cage

brimming with all

that I’d since learned

—our histories that were written across creases that

folded together and cleaved apart and accordioned on–

were recurated like origami blooming on water:

Africans and Vietnamese caged in 19th century French

circus displays of their colonial subjects;

Bụi đời orphans, mixed like me but darker, would have been working bars

with me if I’d been born a few years earlier and an ocean across;

Those hoods hunting us in cities that safe harbored

in hopes of forgiveness of everything they saw burn on screen;

That joining of Yellow Peril to Black Power, berets tilted and fists raised in solidarity;

Our city’s riots that remapped us against each other

through shared walls and streets of shattered glass.

That James Baldwin quote glowing on the wall of the National African American

Museum and its reverberations growing inside you with your first child:

“The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are

unconsciously controlled by it…history is literally present in all that we do.”

Your pride in the self-same cheekbones

you see peeking over N95s during Black Lives Matter marches,

and, at the same time, the nausea you choke seeing those precious three red stripes

–the ones you’d been taught remembered the unity of three distinct regions of the

homeland, the unity that resisted tyranny–

waving alongside Confederate flags

at the Trump supporters’ insurrection at Capitol Building.

Professor Fuller taught me how to look for the braided stories

–the knots, the clicks, the strengthening of adding another strand of story.

And to recognize all the unseeable things

I could never know

that kept me staring at Chantal

and kept her from looking back at me.

I wanted to etch this all on my liver and throw

It in the green grass aisles between rows of slave

Shacks, being “reconstructed,” a small sign read,

“to become part of the tour.”

Toss in, too, my knotted intestines,

That spitting gallbladder,

And my eyes that fleck yellow in Southern heat…

“She called in her soul

to come and see” (193).

The eyes colored

from my father, my mother,

Prof. Fuller, Chantal, Zora,

the ghosts huddling in,

this student.

My dad taught me to always

Get a souvenir—

French, I later learned,

For “remember.”

I tapped photos under my sleeve,

the “no photos allowed” signs,

to archive for my students

who had taught me “Sawubona,”

Zulu for “I see you.”

I wanted to show them how I’d

followed a student in the South,

that I was another,

and that they

could do different too.

Just for today,

“I will study something that challenges my mental ability.”

Just for today,

“I will be agreeable.”

Just for today,

“Happiness is from within.”

Just for today,

I’ll try to make up for something that wasn’t.

Sawubona.

Jade Hidle is the proud multiracial daughter of a Vietnamese refugee. Her travel memoir, The Return to Viet Nam, was published by Transcurrent Press in 2016, and her work has also been featured in Southern Humanities Review, Poetry Northwest, Witness Magazine, Flash Fiction Magazine, The West Trade Review, Bangalore Review, Columbia Journal, New Delta Review, and the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network’s diacritics.org. You can follow her at @jadethidle.