by Sophie Wolf

This bottle-shaped piece of bamboo basketry has a thin neck that widens into a rounded body and base. A torn strip of paper has been attached at the open neck with small metal fasteners, reading “Sibug, No. 2a” in faded ink. This basket is one of a collection of about forty donated to the University of Michigan Museum of Anthropological Archaeology (UMMAA) in 1941 by the Cranbrook Institute of Science just outside of Detroit. This was the same year in which the Cranbrook Institute of Science also received them by way of donation from the Buffalo Museum of Natural Sciences. Although this collection lacks any documentation that might reveal the circumstances surrounding its arrival at Cranbrook, we are fortunate that many of the baskets sport a series of varying tags, marking their previous journeys.

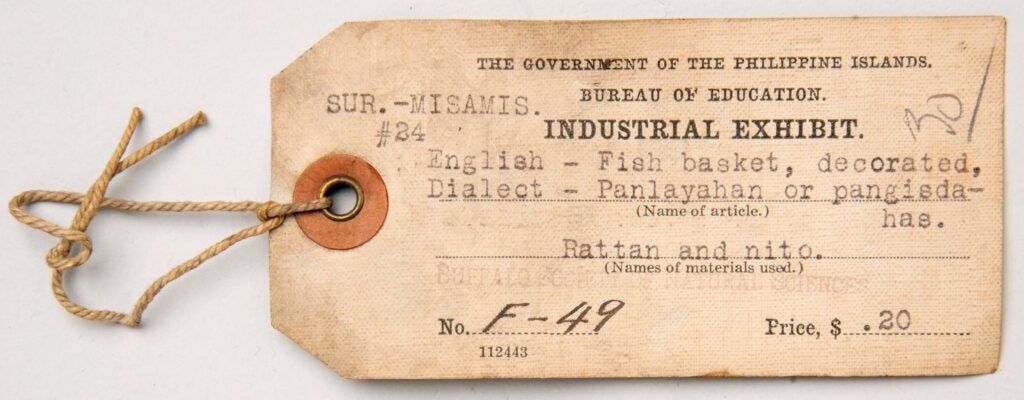

Many of the items in this collection bear attached cloth or paper tags reading “The Government of the Philippine Islands. Bureau of Education. Industrial Exhibit.” These specific tags are known to have been assigned to items intended for shipment out of the Philippines, specifically from the Industrial Museum, Library, and Exhibits of the Bureau of Education. The Bureau was established in 1901 by the American colonial government which took control of the Philippines at the end of the Spanish American War. The creation of a centralized public school system fortified the transition to the new government. The tags list geographic origin, purpose, and whether the basket in question was used or unused: but not one date is to be found, leaving us with only a vague inclination of when they might have made their way to the United States.

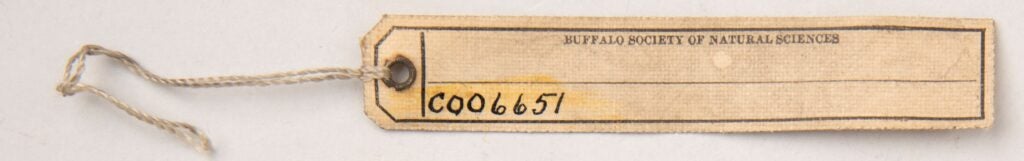

Another less uniform set of tags has been stamped with the name “Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences,” leading us to believe that the baskets first arrived in New York. These types of tags are typical of material gathered to be sent to world fairs and expositions. There were two world fairs held in New York in the first half of the 20th century: the 1939 World Fair in New York City and the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. However the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences (est. 1861) became known as the Buffalo Museum of Science upon opening its doors at its first permanent location in 1929, the same name the institution goes by to this day. Therefore it is logical to assume that the baskets first arrived at the museum prior to 1929. If they were in fact on display in Buffalo in 1901, the baskets may have been originally collected by Frank E. Hilder, a translator to the Bureau of American Ethnology appointed by the Smithsonian to bring back objects representative of life in the Philippines for the Pan-American Exposition. Similar baskets can even be seen in photos taken of the Philippine cultural exhibit in the North Building at the Pan-American Exposition. However, it is possible that they could also have been involved in the fair as a part of a “living zoo”, where Filipino/x people were observed by Western tourists in recreated villages on the fairgrounds.

The University of Michigan museum staff cataloging the item suggested it may have been used to hold rice, but a second tag attached at the container’s base implies it was used as a receptacle for lottery tallies; this could have been of use at the Pan-American Exposition, but perhaps its history goes even further back. The paper tag at the neck that reads “Sibug” provides yet another clue. The people of the Province of Zamboanga Sibugay in Mindanao celebrate its annual founding day at the Sibug-Sibug festival in Ipil, the capital of the Province. The celebration stretches on for several weeks throughout the month of February, though the peak of the festivities occurs on the 26th. Street dances demonstrate harvest, healing, and wedding rituals, and the crowds feast on grilled oysters, or tabala, that can grow up to 12 inches long! As a result of these delicious oysters being found in the area, Zamboanga Sibugay is known as the oyster capital of the Philippines, and the celebration commemorates a plentiful harvest. There are many community activities held during the celebration; perhaps the basket was used for lottery tallies as a part of a game dedicated to the Sibug-Sibug festival, or it simply was made in the Province. “Sibug-Sibug” translates to “move, move”, but “Sibugay” translates to “come closer, my friend”. The festival was held again this year for the first time since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

There is one problem with this theory– the Sibug-Sibug festival wasn’t regularly celebrated until after 2001. The municipality was first documented as a village in an account from 1667 in the province Zamboanga, which was formally divided into northern and southern districts in 1952. A third district, now known as Zamboanga Sibugay, was recognized by law in 2000. Because the area is historic and the Sibug-Sibug festival incorporates traditional cultural ritual, it is possible that the basket was used in some early form of the celebration.

In May 2023 as part of a two-week-long artist residency hosted by ReConnect/ReCollect: Reparative Connections to Philippine Collections at the University of Michigan, three culture bearers traveled from the Philippines to UMMAA in order to engage with the museum’s collections and staff. Master basket weaver Johnny Bangao Jr. indicated that the bottle would have been used to store half-ripe glutinous rice. This rice is typically ground into a flour that may be used in tupig (also subig or supig), a coconut-based snack cooked in a banana leaf over a grill top or in the oven. The culture bearers indicated that this food made with half-ripe rice is typically enjoyed during harvest season. It is also commonly served as a roadside snack. This treat is traditionally prepared in northwest Luzon, especially in the Ilocos Region.

This basket has had a long and complex journey from the Philippines to Ann Arbor. Since arriving in the United States it has been part of the collections of at least four museums over the past 100 years. Even though we know nothing of its life in the Philippines prior to 1901, we can picture its use by a vendor in Luzon to store the rice needed to prepare a tasty snack. In the same year that the colonial government established the Bureau of Education, we can imagine its selection for presentation to an American audience to showcase the wide variety and breadth of Filipino material culture. Despite the colonial circumstances under which the basket left its home, it has been united here at the University of Michigan with fellow Philippine basketry items, including those gifted to the museum this year by master artisan Johnny Bangao Jr. It was his knowledge that gave the basket back its cultural identity.

Bibliography:

Buffalo Museum of Science. “About Us.” Buffalo Museum of Science, www.sciencebuff.org/about-us/. Accessed 27 July 2023.

Bureau of Education, Philippine Islands. The Industrial Museum, Library, and Exhibits of the Bureau of Education. Bureau of Print., 1913.

Mellec-Philippine Festivals. “Sibug Sibug Festival.” Sibug Sibug Festival, 4 June 2010, mellecphilippinefestivals.blogspot.com/2010/06/sibug-sibug-festival.html.

“Part III: Barbarism Exhibited in Buffalo.” The Phillipine Village: Imperialism Exhibited, 19 Dec. 2014, kenn4870.wordpress.com/barbarism-exhibited-in-buffalo/.

“Zamboanga Sibugay, Sibug-Sibug Festival.” FESTIVALSCAPE, 4 Apr. 2023, www.festivalscape.com/philippines/zamboanga-sibugay/sibug-sibug-festival/.

Zamboanga Sibugay. “2023 Zamboanga Sibugay News Celebrates Sibug-Sibug Festival.” YouTube, 26 Feb. 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=kaQXycoggoA.