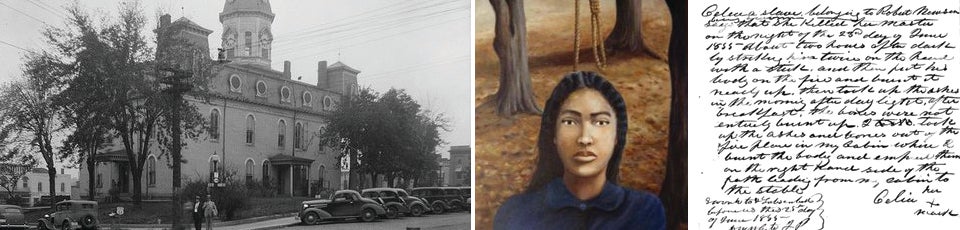

In 1855 Missouri, an enslaved woman named Celia was tried, convicted, and ultimately executed for killing her owner. Celia confessed: She had tried to put a stop to what had been five years of sexual abuse. At the center of the trial was a dramatic confrontation over the legal standing of enslaved women. Did an enslaved woman have the right to defend herself against sexual assault? Drawing on Celia’s own words, her court-appointed defense team said “yes.”

Prosecutors, the trial judge, jurors, and the state high court all rejected Celia’s claim. Enslaved women did not have the same right to self-defense accorded to free women under Missouri law, they concluded. To allow such resistance would have been to strike at the heart of slaveholders’ power. It also would have recognized the legal personhood, honor, and rights of enslaved women, undermining slavery’s legitimacy. In subsequent years, legislators and jurists in other slave states made more explicit that sexual coercion of slaves was not a crime. It is this state sanctioned sexual assault that is a baneful legacy of slavery. Even today, it contributes to erroneous ideas about black women as lacking honor and “virtue,” making them especially vulnerable to sexual abuse.

The Celia Project, a research, publication, and public history collaboration, explores The State of Missouri v. Celia, A Slave and its reverberations in American culture. Our questions are about the role of sexual violence under slavery and emancipation, and its legacy in memory. We are exploring new archival materials. We are engaged with the work of playwrights, artists, and teachers. We are collaborators with activists in Missouri and beyond. Our team of social and cultural historians, literary scholars, and legal analysts brings a expertise to these materials. Celia’s story has transfixed many who seek to explain the legacy of slavery. We invite you to join us.