Welcome to the Cerro Azul Project on the desert coast of Peru. Curator Joyce Marcus of the University of Michigan Museum of Anthropological Archaeology (UMMAA) directed several seasons of excavation at Cerro Azul. The first was devoted to exposing structures built during the Inca era (AD 1470-1530), while subsequent field seasons were spent excavating residences, storage units, middens, and burials of the Late Intermediate period (AD 1000-1470).

The first field season of the Cerro Azul project was supported by a University of Michigan Faculty Fund Grant. The next four seasons were supported by a National Science Foundation Grant (BNS-8301542). Excavation permits were awarded by Peru’s Instituto Nacional de Cultura (Credencial 102-82-DCIRBM, Credencial 041-83-DCIRBM, Credencial 018-84-DPCM, and Resolución Suprema 357-85-ED).

The Kingdom of Huarco in the Cañete Valley

Cerro Azul was one of many key sites in a polity known as the “Kingdom of Huarco.” Research and analyses are ongoing (see the section on “Publications”).

Cerro Azul Project members included archaeologists Ramiro Matos Mendieta, Kent Flannery, Christopher P. Glew, Jeffrey D. Sommer, and Charles Hastings; biological anthropologist Sonia Guillén; ethnohistorian María Rostworowski de Diez Canseco; ethnobotanists C. Earle Smith, Jr., Lawrence Kaplan, and Linda Perry; and coprolite expert John G. Jones.

The Inca Conquest of the Cañete Valley

Midway through the fifteenth century AD, the Inca emperor Topa Inca Yupanqui made his move on Peru’s Cañete Valley. At that time the valley supported two small kingdoms, Huarco in the yunga (coastal plain) and Lunahuaná, 28 km upstream in the chaupi yunga (piedmont).

The Kingdom of Huarco, known for its fierce resistance to the Inca invasion, decided to invest in defensive features at several sites within its kingdom, and in a gran muralla or “great wall” on its inland border. The site of Cancharí, the alleged capital of the kingdom, occupied a defensible hilltop. The takeoff point of Huarco’s main irrigation canal was defended by the fortified site of Ungará. The fishing community on Cerro Azul Bay also constructed a defensive wall.

The Inca strategy was to conquer the Kingdom of Lunahuaná first, converting it into a staging area from which they could attack the Kingdom of Huarco. Ethnohistoric documents indicate that the Inca emperor Topa Inca Yupanqui subdued Lunahuaná around AD 1450.

The Inca Transformation of Lunahuaná

The main seat of Inca power in the Lunahuaná Kingdom was Inkawasi, which according to Cieza de León was a new city to which the Inca ruler gave the name of New Cuzco. Inkawasi played a military and storage function and had a series of walls built nearby to protect personnel and stored goods.

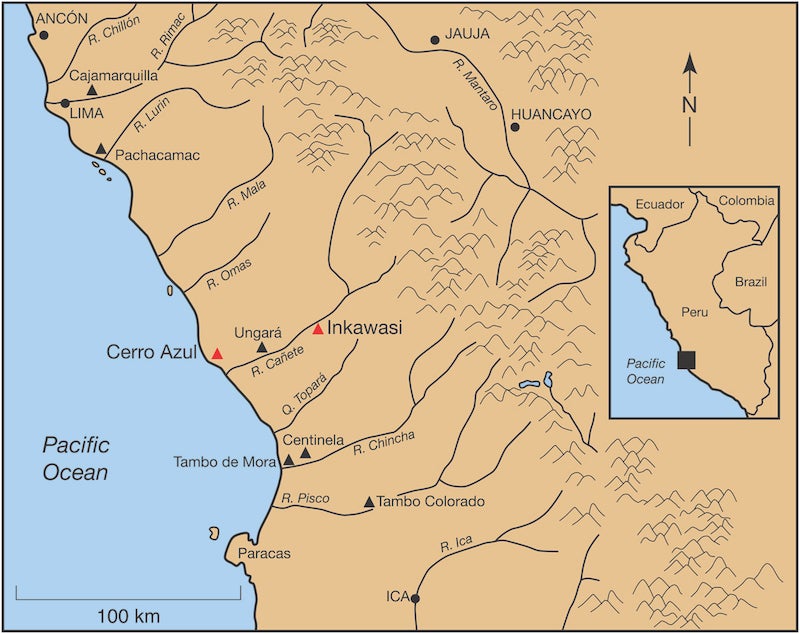

Figure 1. Peru’s central coast valleys include Chillón, Rímac, Lurín, Mala, Cañete, Quebrada Topará, Chincha, and Pisco. The archaeological sites of Cerro Azul and Inkawasi (shown in red) lie in Peru’s Cañete Valley, ca. 130 km south of Lima.

The Inca Conquest of Huarco

Despite the extensive facilities and army that the Inca had stationed at Inkawasi, it took Topa Inca Yupanqui almost four years to subdue the Kingdom of Huarco. Each year the Inca descended from Inkawasi to attack Huarco; each year, with the arrival of the summer heat, the attackers retreated to higher ground. With each retreat, the local agricultural communities within the Kingdom of Huarco had a chance to harvest their crops and brace themselves for next year’s attack.

There are several accounts of the eventual conquest of Huarco in AD 1470. Some attribute the Inca victory to deception— the Inca are said to have proposed a truce that turned out to be the pretext for a sneak attack. Convinced that the Inca genuinely wanted peace, the battle-weary people of Huarco decided to celebrate the truce with a ritual that required them to enter the sea in their watercraft. While the Huarco defenders, fishermen, musicians, and religious specialists were out at sea, the Inca attacked.

When we turn from the ethnohistoric documents to the dirt archaeology of Cerro Azul, we find evidence that the Inca constructed ritual buildings on the sea cliffs overlooking the Pacific. One of these was an adobe building with trapezoidal niches.

Figure 2. This Cerro Azul building was contoured to the steep cliffs. Trapezoidal niches can be seen at lower right and in Figures 3 and 4.

Figure 3. The lower room features trapezoidal niches, an attribute of Inca-era architecture.

Figure 4. Close-up view of the trapezoidal niches of the same structure seen in Figures 2 and 3.

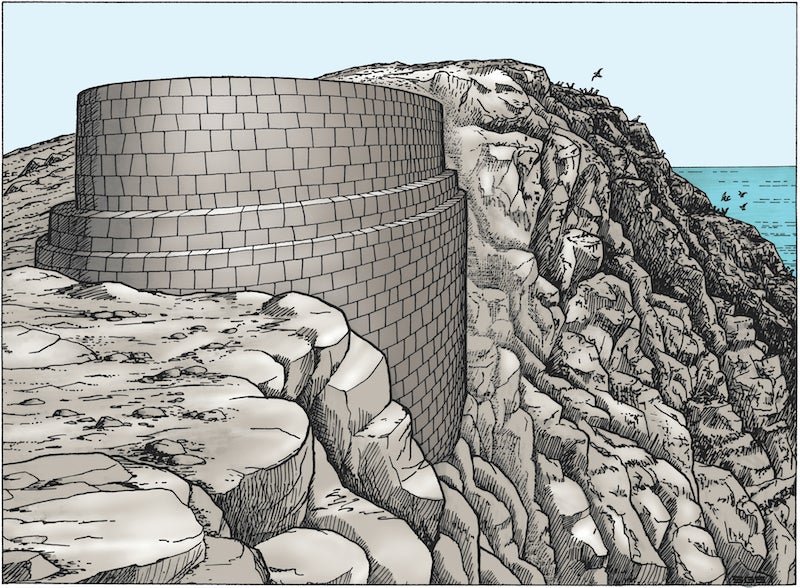

Another building was built of cut stones and equipped with a stairway to the sea. Of all the Inca buildings at Cerro Azul, this building is the one most prominently mentioned in the documents. It was once a magnificent oval platform, visible from many kilometers out to sea.

Figure 5. Artist’s reconstruction of an Inca-era building whose stone stairway once led down to the ocean (drawing by David West Reynolds; colorized by John Klausmeyer).

This building was approximately 30 meters in length, 11-13 meters in width, and 5.6 meters in height. It was perched on the sea cliff in such a way that part of it projected out over the ocean. From this platform, a stone stairway descended the sea cliff all the way to the water, so that offerings could be made directly to the sea. Along the rugged and precipitous course of this stairway there were balconies, some of which survive today.

The Late Intermediate Community of Cerro Azul (AD 1000-1470)

By far the bulk of Cerro Azul is pre-Inca, dating to AD 1000-1470. This Late Intermediate occupation is concentrated in a protected basin, between an 86-meter-high mountain and the steep sea cliffs. The site’s most prominent Late Intermediate features are 10 large buildings, eight of which (Structures A-H) surround a plaza. These structures appear to have been large residential compounds occupied by elite families, their staff, and servants.

Figure 6. Map of Cerro Azul, showing location of Late Intermediate residential compounds (labeled A to H). The Michigan team excavated Structures D and 9 in their entirety, as well as the Inca-era buildings (labeled 1 and 3 in red).

For centuries, the refuse from these residential compounds was carried to the slopes of a nearby mountain called Cerro Camacho. Over time, the accumulating refuse was used to create a series of artificial terraces. Once some of these terraces were deep enough, they became suitable places to create subterranean cists for burials. In some cists the project found mummy bundles containing individuals whose social status was expressed not only in elaborate textiles, dyed camelid wool, exotic pigments, pyroengraved gourds, and incised needlecases, but also in their access to gold and silver.

A museum built at Cerro Azul displays material from the UMMAA project as well as more recent excavations at the site.

Structure D, Cerro Azul

Structure D is one of the eight residential compounds surrounding an irregular plaza. The building, which covers 1640 m2, was made of tapia (thick walls created by pouring mud between wooden planks). Almost every one of the rooms or patios of the compound served a different function, and some rooms were repurposed over time.

Structure D was the residence of an elite family and its support staff. Divided into a dozen rooms and four major unroofed work areas, Structure D included living quarters with built-in sleeping benches; multiple storage units; corridors that controlled access to the interior of the building; places where weaving had been carried out; rooms for raising guinea pigs; units where massive numbers of fish had been stored in layers of sand; and a “kitchen” area that served as a brewery where chicha (maize beer) was manufactured.

Figure 7. Structure D, one of the large tapia compounds at Cerro Azul, was the residence of an elite family and its support staff during the Late Intermediate (AD 1000-1470).

The original layout of Structure D had been changed several times during the building’s occupation. Some of this modification appeared to have been forced on the occupants by earthquake damage. Some residential quarters —severely damaged by earthquakes— had been converted to fish storage units. A few doorways had been blocked off in order to change the circulation of traffic.

It is fortunate that Marcus was able to excavate Structure D in its entirety, because the omission of any room would have left one of the building’s functions unstudied.

Structure 9, Cerro Azul

Having completed the excavation of one of Cerro Azul’s ten major residential compounds, Marcus decided to investigate one of the smaller buildings nearby. The nearest of these, Structure 9, lay on a natural promontory southwest of Structure D.

Figure 8. Many rooms of Structure 9 of Cerro Azul were devoted to fish storage.

Structure 9 turned out to be a multiroom building covering roughly 290 m2. Sweeping the surface of the structure before excavation revealed at least 15 rooms or patios. Structure 9 turned out to be a fish storage facility whose commoner-class overseer lived in a kincha hut. Structure 9 showed two trends also seen in Structure D: (1) an increasing need for more fish-storage capacity; and (2) changes in room function brought on by earthquake damage. The commoner overseer may have reported to the elite family occupying Structure D.

Copyright © 2021 University of Michigan Museum of Anthropological Archaeology (UMMAA)