In the Andes, spinning and weaving have traditionally been considered women’s work. It is therefore not uncommon for women’s mummy bundles, all along the coast of Peru, to contain weaving equipment.

At Cerro Azul, many Late Intermediate elite women were buried with the textiles they had been working on at the time of their death. Burial items could include looms, weaving swords, bags of yarn balls, or decorative piping.

One elite woman at Cerro Azul was buried with a bag that showed signs of having been repaired more than once, evidently a valued possession. Inside the repaired bag was everything she needed to paint her fingernails— pouches with red pigment and three giant mussel shells that served as pigment dishes. The paint on her nails was identical to the paint in the shells.

Some women were buried with their looms, workbaskets, spindles, spindle whorls, needles, bags of yarn balls, skeins of colorful threads, and textiles. This burial practice allowed Marcus to see each elite woman’s chosen yarn colors, which could then be compared to those used in her unfinished textiles.

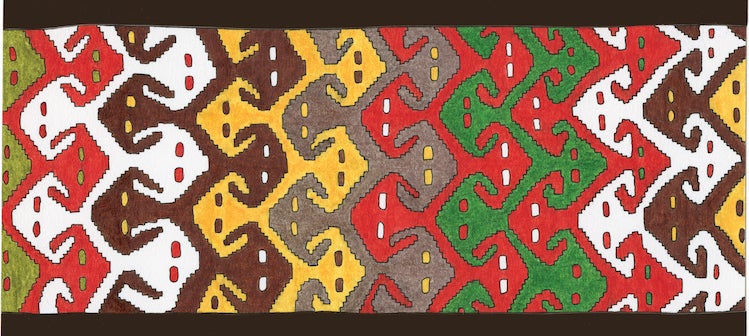

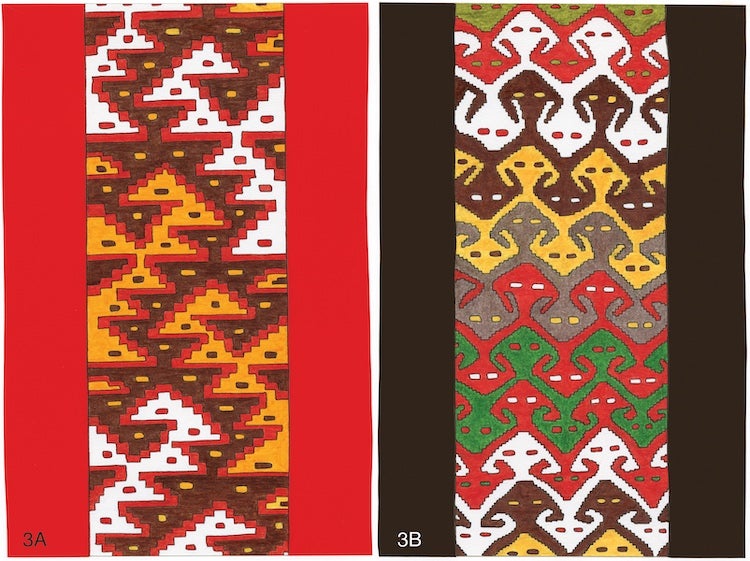

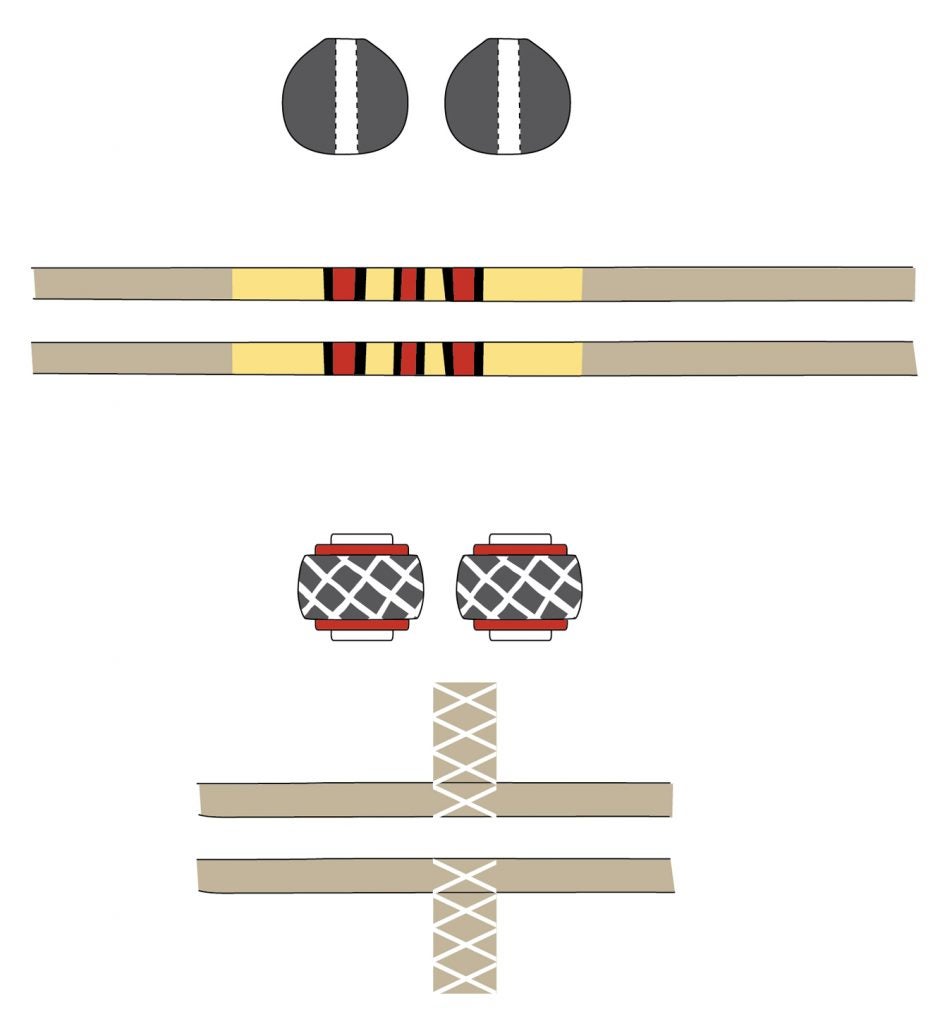

Many women were associated with at least one workbasket and two colorful belts used as loom backstraps. Such belts are referred to in Quechua by the term chumpi. A woman’s individual stylistic preferences were expressed most clearly in each chumpi’s tapestry panel, which usually measured 5 to 8 centimeters in width. These preferences were striking, even when two women happened to be buried in the same stone masonry burial cist.

The Cerro Azul Project recovered eleven of these chumpis; all were two-sided. On one side the central tapestry panel was flanked by solid red bands; on the opposite side, the flanking bands were solid brown or black.

One woman, 35 to 39 years of age, had been buried with an infant and a child. Her fingers had been tied together, and her wrists and arms had been tied in front of her chest, presumably to keep her extremities in place as she was wrapped in her bundle. One of her two chumpis was still in place around her hips.

This woman was accompanied by her workbasket and a tied cloth bag, both still filled with their contents. Her workbasket included empty spindles, spindles with the thread and whorls still on them, and abundant colored thread and yarn. Her food for the afterlife, placed in a gourd vessel, included maize, lúcuma fruit, three large sardines, two clams, two mussels, one abalone-like chanque, and two guinea pigs. Two pottery vessels and a tied bundle of bulrush was placed with her, and there was a piece of silver in her mouth.

Marcus found a second woman with a piece of silver in her mouth. In this case a false head, formed of cloth and reeds, had been placed at the top of her mummy bundle. That bundle consisted of an outer coarse textile and a dozen brown-and-white-striped interior textiles. Between the outermost coarse cloth and the striped cloths were three chumpis, as well as small folded sheets of silver and gold.

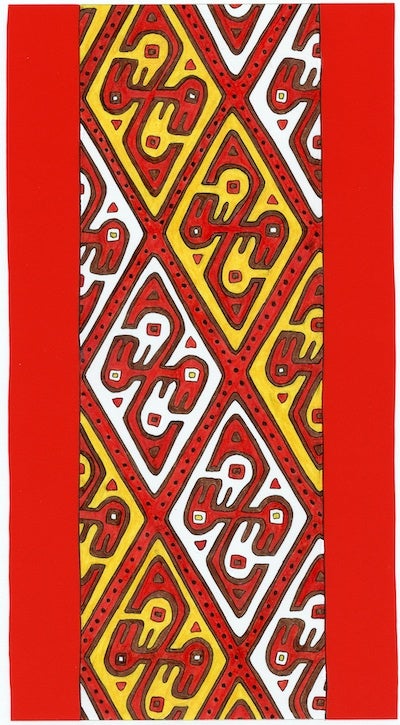

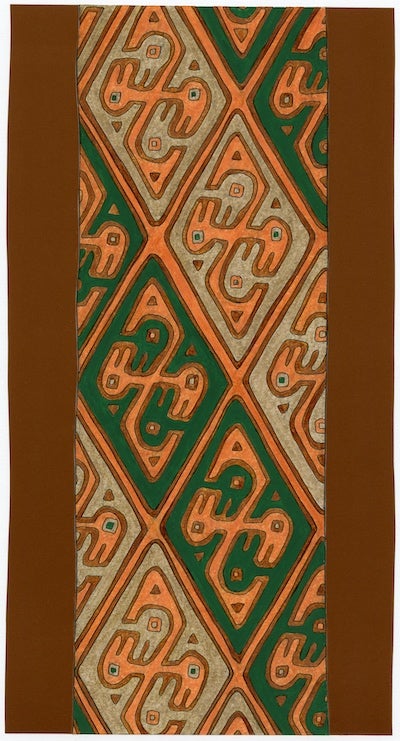

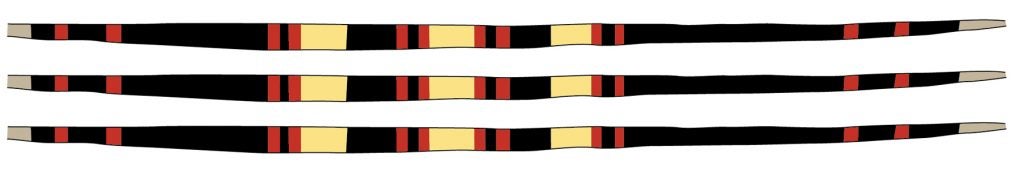

The style preferences of the two women with silver in their mouths were as follows. Each woman had one chumpi with motifs identical to one of the other woman’s; however, the first woman had executed those motifs in red, yellow, and white, while the second woman had executed them in forest green, gold, and brown (Figures 55, 56). Each of these women also had a second chumpi bearing a design that was unique to her.

Figure 55. (left) This woman’s chumpi featured stylized birds in red, yellow, and white.

Figure 56. (right) This second woman’s chumpi featured the same motif seen in Figure 55, but done in forest green, gold, and brown.

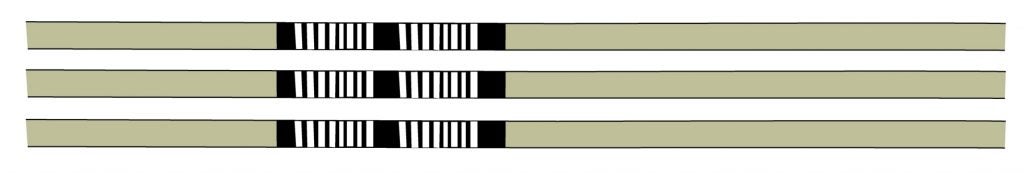

In addition to expressing their style preferences in chumpi design and color, elite women also personalized their spindles by painting them with stripes that formed a “barcode.” Each barcode combined stripes of different colors and widths (for more information, see the 2015 article entitled “Studying the Individual in Prehistory: A Tale of Three Women from Cerro Azul, Peru,” in Ñawpa Pacha: Journal of Andean Archaeology 35, pp. 1-22; and the 2016 article entitled “ Barcoding Spindles and Decorating Whorls: How Weavers Marked Their Property at Cerro Azul, Peru,” in Ñawpa Pacha 36, pp. 1-21).

One woman buried at Cerro Azul was accompanied by her workbasket, a complete belt loom, and the wooden stakes used for setting up her loom. Among the items in her workbasket were five spindles, two of which were unpainted. The other three spindles were painted with an identical barcode— a black band followed by eight white lines, another black band followed by eight white lines, and a final black band. On all of her identically painted spindles she had wound yarn of the same color, yellowish brown; in contrast, the yarn on the unpainted spindles was dusky red. Thus barcoding could be used not only to identify a woman’s personal property, but also to segregate yarns of different colors.

Copyright © 2021 University of Michigan Museum of Anthropological Archaeology (UMMAA)