LISTEN TO SAFE SPACES PODCAST

https://umich.box.com/shared/static/sgxxbqhh7t67nnq1dmkpvhwp7vp16wkx.mp3

Download

In this episode, we’re listening to the voices of Dr. Stephen Ward, Dr. Lee Gill, and Sena Adjei-Agbai as we explore where and how students from historically marginalized identities have found safe spaces to live, learn, and lead together.

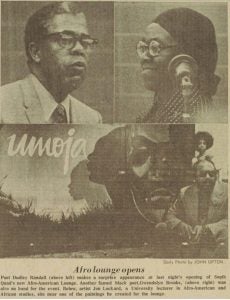

Photo from left to right

Stephen is an associate professor in the department of Afroamerican and African Studies and the Residential College.

Sena is a Ghanaian-American transfer student studying Political Science and Economic at the University of Michigan.

Lee brings more than 25 years of private and public sector experience working with major corporate executives, law firm executive committees, and college presidents. Lee holds a Bachelor’s degree in Political Science and Sociology from the University of Michigan and his Juris Doctor Degree in law from the Illinois Institute of Technology, Kent College of Law.

Chapter 1: A Latina’s quest to find the multicultural lounges at the University of Michigan

You’re not supposed to be here.

Trying to find a study spot in the summer, I learned there were multicultural lounges available in the dorms. Wanting a change in scenery, I made my way down East University to visit the multicultural lounge in East Quad. Scrambling for my MCard, I realized I might not have access to the building.

Denied. No green light for me.

I had seen a couple of students walk in the other entrance so I walked around and waited for my opportunity. Someone walked out and I dashed to the door hoping I could reach it in time. Access granted!

Looking around, there’s the closed cafe, empty of course, the hallway leading to the dining hall, and the stairs to the basement. I search for signs, something reading Abeng or Multicultural Lounge, but had no luck.

I asked the community center staff, figuring they would know since they organize room reservations in the res hall. “It’s in the basement,” was followed by “why” and “for what?”

Ah, they probably thought I was a freshman at orientation. “I would like to access the Abeng lounge,” I told them, “but I’m not part of the orientation.”

“You’re not supposed to be here” they said. “It’s for the safety of the students staying in the dorms.”

A similar situation happened to my friend during the winter semester. She was trying to study with a group of friends in the Asubuhi Lounge in West Quad, but none of them had access. They attempted to sneak in there when the door was open one evening, but once they walked into the lounge, the three people already present told us them they needed to leave because they weren’t members of the multicultural community in the West Quad dormitory. The people made it fairly obvious that my friends did not belong in the Asubuhi lounge.

All this got me thinking, what do students of color have to do in order to attain access to lounges that were designed as safe spaces for us?

Chapter 2: How were the lounges formed?

Let’s back up a bit. What makes these lounges spaces where students of color can “interact with one another in a relaxed and open environment” and find “ havens for support, solidarity, and sharing?” Though there are 16 multicultural lounges across the various residential facilities, the history of how these spaces came to be is often obscured or inaccessible.

Much of the development of these spaces was the result of student activism. Policies and practices of segregation meant that students of color were often restricted to certain areas – for living, for studying, for socializing. In 1949, the Office of the Dean of women, for example, used photographs attached to housing applications to assign roommates. If a Black woman did not designate a roommate, she would be placed with another Black woman or placed in a single room. Such rooming policies continued, leading to a petition in 1957 that the University of Michigan investigate discriminatory practices in housing and abolish the use of photographs on applications to the residence halls. Though non-discrimination polices for student groups were around since 1949, it wasn’t until 1959 that the University Regents established a bylaw that “the University shall not discriminate against any person because of race, color, religion, creed, national origin, or ancestry.” It was not just in residential housing that students of color faced challenges in housing. In Ann Arbor, the passage of the Fair Housing Ordinance in 1963 was the first resolution in the state of Michigan to prohibit discrimination in housing rentals and sales, which was connected to continued school segregation.

Where polices didn’t control behavior, however, social norms and practices took the reins. Imagine entering a space – any space, a classroom, a dining hall, a courtyard – and you notice that people are both looking at you and not looking at you. You scan the crowd looking for someone who looks like you, or someone who is also a person of color. At first you may feel like you have to get out of the space as quickly as possible, and that’s when the thoughts rush in I think I made a mistake. I shouldn’t have come here. Why didn’t I take the other street? Why didn’t I choose another school? The flow of questions can infuse each step with doubt and and make you feel like you don’t belong.

Recognizing that the issue of space was central to inclusion and equity at the University, the first Black Action Movement identified the need for a Black Student Center in a list of demands. Accompanying the formal demand was recognition for spaces in the residence halls for Black and other students of color. The request included living space or culturally centered and designated residence halls, which was rejected by the Regents, and was later altered to lounges and libraries.

A house, previously used as a home economics space by the University high school, was converted to primarily serve Black students at 1020 South University (on the corner of South University and East University-present location of the School of Social Work) became the Trotter House through the Martin Luther King Scholarship Fund (similarly established a result of the Black Action Movement). After the space was damaged by a fire, the University used a fraternity house on 1443 Washtenaw as the new site for Trotter. Accompanying the opening of the new Trotter space were lounges and libraries in South Quad (Afro-American lounge) and Stockwell (Rosa Parks lounge) residence halls primarily for Black students (as an alternative to addressing the residence halls concerns expressed by BAM activists).

Since 1971, student activists have pressed for spaces of community and understanding, spaces where they would feel included and see themselves represented. They fought for safe spaces, some of which are highlighted below (a complete list of the cultural lounges can be found on the Michigan Housing website).

Abeng Lounge – East Quad

The first of its kind, the establishment of the Abeng lounge was part of demands that Black students presented to the Representative Assembly of the Residential College following the students checking out and hiding every book in the dorm library as protest against the East quad librarian for not replacing a $600 collection of records on black themes stolen over that summer of 1972.

Afro-American lounge – South Quad

The Afro-American or Ambatana lounge opened in the spring of 1973 (March 28) in South Quad and was commemorated with poets Dudley Randall and Gwendolyn Brooks as well as an appearance by Jon Lockard who created the paintings for the lounge.

Cesar Chavez – Mosher Jordan

The Cesar Chavez Lounge had its dedication ceremony on April 4, 1995 in what used to be called the Mosher-Jordan Multi-Purpose lounge. And this marked the first University residence hall lounge named after a Mexican-American. La Voz Mexicana and the Mosher-Jordan residence hall planned the dedication that took place during Latin American week.

Floricanto was Alianza’s annual event that took place during Chicano/a History Week at the Cesar Chavez lounge. In the 2001, they were able to fundraise 20,000 for five murals for the lounge.

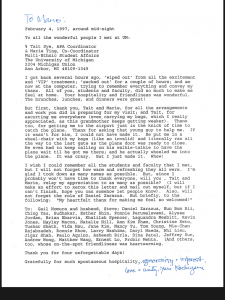

Yuri Kochiyama – South Quad

The Yuri Kochiyama lounge, dedicated on February 3, 1997, was the first lounge dedicated to an Asian American at a residence hall at the university. Honoring her years of activism in the civil rights movement and the black nationalist movement, Daniel Zarazua (minority peer advisor) led the effort behind the lounge’s renaming along with Tait Sye, Marie Ting, and Ann Pham.

Vicky Barner – Alice Lloyd Hall

The Lounge dedication took place November 19, 2000 with the help of the Alice Lloyd residence hall staff, the Native American Student Association and the Native American Law Student Association. NASA chose to dedicate the lounge to Vicky Barner for her involvement in the Native American community. She created the group American Indians Unlimited that created Ann Arbor’s first student run pow-wow as well as being an activist protesting the racism of Michigauma at the university of Michigan.

Edward Said – North Quad

The Edward Said lounge is the most recent Multicultural lounge dedicated in February of 2015. The idea of an Arab-American themed lounged had been under consideration by the North Quad Multicultural council for about 3 years and became a leading topic of debate at a UM Divest sit-in protest in 2014. Students Allied for Freedom and Equality had put forth a divestment resolution towards CSG to help in calling on the university to divest from companies that had supported human right violations against Palestinians, when CSG decided to postpone action on the resolutions SAFE members occupied the CSG chambers to demonstrate that they were not to be silenced. One of the sit-in organizers, Suha Najjar, stated, “There is no safe space on this campus and we asked the administration for an Arab Lounge similar to what other campus populations have achieved. This is something students on this campus have been trying to get the ball rolling for six years.”

Chapter 3: Trotter House or Trotter Multicultural Center

The question of safe spaces still remain. As the overall student of color enrollment increased and the communities represented became more diverse, issues with the off-campus location of Trotter and the condition of the facility came to the forefront. Concerns with Washtenaw Avenue location raised in meetings predating the move now became highly publicized through student activism. Comparisons between peer institutions and UM’s Trotter facility highlighted the need for improvements, particularly for an institution that positioned itself at the forefront on social justice issues. While many prior voices raised concerns, the “New Trotter” movement became solidified beginning in 2013. The efforts of all helped to center the voices of those often on the margins and resulted in the announced construction of a new facility to be located on State Street.

Just two weeks ago, on Nov. 8, 2017, the new Trotter Multicultural Center on State Street broke ground. Standing with students, staff, and faculty, U-M faculty member Elizabeth James was moved to tears, as years of activism and dedication across generations led to this moment. Trotter symbolizes both the struggle for safe space for marginalized groups, but also the accomplishments of these groups mobilizing and voicing their concerns. Coming into reality as the result of the first Black Action Movement, Trotter continues to be a place for communities to gather and organize. Critical conversations surround the location of the space–even as this location changed throughout the years–emphasizes the necessity of centering Trotter to align with the communities it was intended to serve. From its inception to the present, Trotter plays a vital role in providing space for marginalized communities.

Contributors: Barbara Diaz, Alexis Gonzalez, Richard Nunn, and Tonya Kneff-Chang