LISTEN TO CONSTRUCTING COMMUNITY PODCAST

https://umich.box.com/shared/static/25wwishpvhv2m9bmo97jabu3epeweuit.mp3

Download

In this episode, we’re listening to the voices of Dr. Maria Cotera, Dr. Jaime Chahin, and Yvonne Navarrete as we explore access to diversity and student contributions to communities on campus to further connect, advocate, and strengthen dynamics of campus movements at the University of Michigan.

Photo from left to right

Maria is an associate professor in the Department of Women’s Studies and American Culture, as well as the Director of Latina/o Studies at the University of Michigan

Yvonne is a sophomore at the Ford School of Public Policy, concentrating on education policy and current Lead Director of La Casa: the Latinx umbrella organization on campus.

Jaime is a professor and Dean of the College of Applied Arts at Texas State University. He holds both a Master’s in Social Work and a Ph.D. in Social Work and Education Administration from the University of Michigan.

Finding solidarity in the intersections of community

A significant voice in creating the diversity the University defends and celebrates are the efforts of students and other community members. Focusing on access as key to achieving diversity, it is also relevant to recognize the contributions of these same community members. Undertakings in the Latinx community include graduate student recruitment initiatives, initiated by students of the community, to increase representation at the graduate level, specifically in Social Work and Education. More contemporary representations of this struggle also include the Assisting Latinos to Maximize Achievement (ALMA) program, a student created program that connects incoming students with the community before the academic year. Understandably, access also becomes nuanced and students again respond to these dynamics through movements like the Coalition for Tuition Equality (CTE) and advocating for instate tuition policies for undocumented/DACAmented students. As students fight to create and achieve access, there is also intentionality in how they construct their community.

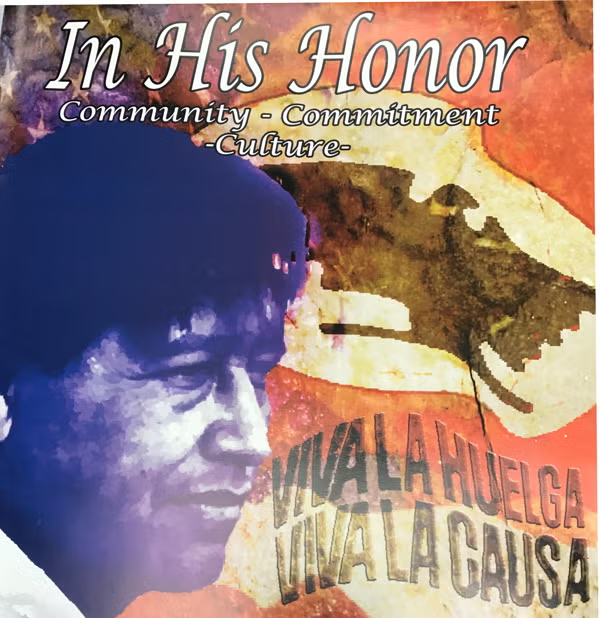

The evolution of the Latinx community is penchant for construction and reconstruction, to build and rebuild when circumstances change. As the community needs change, the community redefines itself, suggesting permeable borders of inclusion. However, reconstructing and rebuilding community has its challenges. Although there may be a need to reconstruct as changes occur, it may be necessary for the Latinx community to consider who or what makes the community and how this may influence sustainability. Shifts in demographic changes can influence new realities that offer opportunities for greater alliances. Bringing together culturally different groups for issues that unify support has caused the Latinx community to grow. For instance, students joined in support of boycotting California grapes in 1973 to ensure safe and just working conditions for farm workers. Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers (UFW) Union, organized workers, and local volunteers in Michigan brought the boycott to Ann Arbor to protest the A&P store on Industrial and Stadium. A&P was the largest buyer of produce in the Midwest from non-unionized sources. MSW’73 Arturo Rodriguez was one of the students involved, and speaks to the larger impact the union had, and how people can come together to improve conditions through the power of organizing. Creating alliances across difference takes work, work the Latinx community has undertaken constantly, but it also requires resources, flexibility, and existing in a constant state of change.

Despite different nationalities, students may identify as Latina, Latino, Latinx, Boricua, Chicano, or Hispanic, with each term representing a unique identity, sometimes situated in a context informed by place, history, and political environment. Terms may be used to refer to the same group(s), community, or members in a community. At times, choice of term can create division and may impede unity in a community of diverse people. Who is using the term is also important when considering the context because there is power in having ownership and choice in how one identifies. Constructing community among a diverse set of people and building retention in educational settings is both historical and one that still resonates today. In 1992, the Socially Active Latino Students Association (SALSA) hosted a number of events for Chicano History Week, including a keynote, workshops, a movie showing, and dance performances. SALSA strategized for student participation and engaged in efforts to recruit and retain Latino/a students in higher education.

In 1995, another major grape boycott was staged by the UFW protesting the exorbitant use of toxic pesticides. U-M’s Alianza, the Latino/a Student Alliance, expressed their solidarity and encouraged the larger community to boycott. U-M Food services director eliminated California grapes from the dining halls, but attributed his decision to hearing a speech by Cesar Chavez. Students, who had been protesting and organizing for a boycott of grapes for months, expressed frustration over not being heard, to which he responded, “If there was a legitimate attempt to follow official procedure…their voice would have been heard.” Institutional responses to student community action often demonstrate the complexities of systems that often dismantle the foundations of change that were build on the backs of student advocacy. Community protesters were U-M students of all backgrounds, not necessarily Californians, or farm workers or children of farm workers, but regardless, they came together to fight for what is right, and to fight for something that affected their community in multiple aspects.

This past year, when racist flyers were posted around U-M’s campus and the political hostility increased with the election of Trump, the media outlet Noticias Telemundo came to campus to interview undocumented students. The Latinx community demonstrated support for these students by attending and joining the a conversation around the issues of undocumented students. Being undocumented was not the requisite for joining the conversation; rather, it was the interests of having conversations around issues that affect the community as a whole, that brought people together and fostered community. The question of impact on the community goes beyond a direct impact on the individual because impact transfers into local and national community construction among various ethnic and national identities.

Due to the new presidential administration, individuals continue to question their voice in community advocacy and the safety of students on campus and it doesn’t help that there was an incident where the U.S. Customs and Border Protection was here on campus. Among the Latinx community, some are undocumented students on campus. Therefore, the presence of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection made it worse for these individuals. An action that the Latinx community took was the idea of conducting a meeting with Michigan administrators, providing two latino organizations-LACASA and the Latinx Social Work Coalition-to unite together, for they wanted to ensure that Latinx students (e.g., undocumented students) felt safe walking on campus. Both latino organizations united and wrote a letter to the administrators highlighting the following: “We believe that the presence of CBP deeply contradicts much of pro-immigrant stance UM administration has made in the previous months,” the letter reads. “Indeed, it is difficult to trust that the University stands with students and faculty who were banned from entering the US by Trump’s Executive Order when the Administration allows for the recruitment of agents who would enforce the ban itself.” The Latinx community continues to fight for their beliefs and their protection here on campus.

Contributors: Thalia Maya, Alexis Gonzalez, and Barbara Diaz