Nonfiction by Matthew Lansburgh for MQR Online.

First, I should note that my subject is a topic civilized people rarely discuss. We are here to talk about money. The discussion will be crass. Incriminating details will be disclosed, actual figures cited. One or more of the people involved in the events described below witnessed and/or experienced divorce, heartbreak, and shoplifting.

Some context: my father grew up wealthy, my mother poor. She was born in Germany in 1935, and, when the bombs began to fall, she and her mother and brother moved from their home in Leipzig to a hut in Bavaria. Even now, at the age of eighty-two, she still reminds me that the three of them were forced to live on a few slices of bread per day. They ate rotten potatoes and raised rabbits for a modicum of protein every month or two.

My father was raised in Washington, D.C. His parents owned a large department store; they had a maid and a cook, and they threw elaborate holiday parties. I have a photo of my father and his family walking on a boardwalk in elegant outfits, looking very Great Gatsby. For his eighteenth birthday, my father received a teal Pontiac Streamliner. As my mother used to say, he was born with a sterling spoon in his mouth: he went to an elite college and spent his life dabbling—in art, travel, marriage. He inherited a trust fund that paid him a generous sum of money four times a year.

My father fell in love with my mother a few years after she arrived in the United States to work as a maid. Days after my third birthday, he divorced her. At the time, she wanted to hire a lawyer to ensure his alimony and child support payments would be sent to her directly from his trust fund. She knew my father was irresponsible, that he always spent more than he had, and she was afraid he wouldn’t send her the $400 a month he’d promised.

My father wasn’t all bad: he could be charming and playful, creative and whimsical—he often sent me handmade birthday cards with drawings of rabbits or elephants or giraffes, usually with a check and a handwritten note. But he could also be short-tempered and domineering. He barged into restaurants, insisting on being seated immediately, even if he didn’t have a reservation and there were people in line. He broke the speed limit and cut other cars off, unleashing a string of expletives when drivers gave him a dirty look or flipped him the bird. When my mother told him she wanted to hire her own lawyer during the divorce, he insisted his attorney could represent them both. He said if she made things difficult, he’d take her to court and ensure she got nothing.

She acceded to his demands and, invariably, his checks arrived late, sometimes by three or four months. She and I moved from Colorado to California. We lived in cramped apartments, rented rooms from people who needed extra cash, stayed with men my mother met at the beach or in one of the odd jobs she found to make ends meet. She worked as a secretary and a receptionist for a hotel, and for a time, in the office of a company that sold RVs. Throughout my childhood, she talked about money constantly. She compared prices of even the most inexpensive items; she perfected the art of returning clothing and household appliances and other things she’d purchased from K-Mart; she learned to extract value from people around her—asking boyfriends to fix her car or help paint the bathroom, pleading with neighbors to babysit, shaving nickels and quarters off every transaction she touched.

By contrast, my father squandered funds with abandon. He bought crucifixes from France and carvings of Saint Sebastian and the Virgin Mary made of walnut and oak. He paid tens of thousands of dollars for illuminated manuscripts depicting angels with lyres and gitterns, then sold them at a loss when he needed cash. I visited him for six weeks each summer and ten days at Christmas. Sometimes, when he lost his temper and I clammed up, he pulled a silver dollar out of the glove compartment of his car and gave it to me. He took me to movies where he purchased boxes of Milk Duds and red licorice. When I was nine or ten, I spent Christmas in Aspen with him and his girlfriend along with her son and my half-siblings, Mark and Ann. After we finished opening our presents, Ann cracked open one of the walnuts in her stocking. Inside was a crisp $100 bill, folded into a tiny paper block. Immediately, everyone began to open all of the walnuts in sight and there were hundred dollar bills everywhere.

My father was a person ruled by contradictions. He criticized people who drew attention to themselves—not just braggarts and know-it-alls, but also people who wore fancy clothes or laughed with abandon—yet he himself frequently made a spectacle of himself. He hired an artisan to fashion a leather belt for him to wear with his Levi’s, a strip of thick leather studded with flat silver shells and a heavy buckle. At restaurants, when he was feeling playful, he rolled up pieces of bread and stuffed them into his nose and ears; often when he saw a man out in public with a cowboy hat or tattooed biceps, he staged a confrontation. “Here comes a tough guy,” my father might shout, or “I bet this one’s from Texas!” At least two or three times during each of my vacations, he’d challenge a stranger to an arm-wrestle.

He liked living on the edge. Even on the narrowest mountain roads, he broke the speed limit, passing every car in his way. He made inappropriate comments and gestures in public and relished playing practical jokes. Against everyone’s advice, he spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on technology options at the height of the tech bubble, leaving himself insufficient savings to cover his bills. Not surprisingly, he died broke, owing more than fifty-thousand to Visa and AmEx. After years of boasting about the vast sums of money he was going to bequeath his children, he had nothing left. If he’d lived another six months, the bank would have foreclosed on his modest house.

By contrast, my mother—who is still alive—is quite wealthy now. She scrimped and saved to buy a duplex in Summerland, California, then used the rent from that property to buy another home. Currently, she owns four houses; by the time this essay is published, it will probably be five. She collects my deceased stepfather’s pension and Social Security checks. She accumulates rent from her various tenants. Even now that her income is significant and she has more than she’ll ever be able to spend, however, she still buys the cheapest cuts of meat. She still buys discounted produce, still drives out of her way to save a few cents on gas. When I visit her and want to eat out, she calls me a high roller. To her, restaurants are a waste of money. Even at Denny’s she’ll order the cheapest thing on the menu—a cup of soup or a small salad. When my food arrives, she’ll ravenously accept as many bites as I offer.

A few months ago she called to tell me about some carpet she needed to replace in one of her rental properties. She complained about how hard it was for her to pull up the carpet from the floor and cut it into pieces, then drag it into the trunk of her car so she could take it to the dumpster.

“Why are you doing all this?” I asked. “Why don’t you pay someone to help you?”

“I called the gardener, but he wanted seventy-five dollars. I do it myself.”

“What if you hurt yourself? It’s not worth it.”

“Ach,” she said. “Don’t always worry so much. Money doesn’t grow on trees.”

It struck me that my mother’s desire to be frugal is, in some ways, the obverse of my father’s profligate nature. To her, saving money is a kind of game. She gets a high from seeing how thrifty she can be. Saving seventy-five dollars by removing the carpet herself or shaving three cents off a gallon of gas isn’t really about the money. It’s about the chase.

++

When I was a boy, my father lived in a one-room house he built by himself—or, rather, that he designed and had built by a contractor. It had thick concrete walls, small windows, and antique doors from England and Spain, assembled from slabs of oak studded with decorative hardware. This octagonal fortress, full of medieval manuscripts and lamps made of ceramic jugs from the Tang dynasty, sat on the edge of a forest, in the middle of a large parcel of land outside Colorado Springs. My father slept in a king-size bed, cordoned off from the rest of the space by floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. I slept on a narrow mattress under a large printing press.

Every time I visited him, he pointed out various pieces of art in his collection, telling me how much he’d paid for them, how much they were worth, and who would inherit them after he died. Mark would receive the German lectern carved by thirteenth-century monks; Ann would inherit the bronze ram cast by a Roman sculptor my father called an artistic genius; the limestone carving of six of the twelve apostles—dating from a French church built in the late 1400s—was earmarked for me. I don’t remember the purported values of the pieces, but as I recall, each was worth somewhere in the range of $150,000 to $350,000. I was too young to understand why their values should matter to me. I had no idea what $150,000 could buy.

When he died in 2013, my father owned neither the lectern nor the ram nor the limestone apostles. Each item had been sold off during periods of financial hardship. In the late 1990s, my father’s ownership interest in the Washington, D.C. department store was liquidated and he received a large check. He used the first installment of this payout to buy silver on margin and had no problem spending the balance of the funds he received—bestowing lavish gifts on women who caught his eye, purchasing new four-wheel-drive cars, making foolhardy investments.

Do you see why he died penniless? Do you understand why one year, when he was in his seventies, I sent him a gift card to buy his Thanksgiving meal? How many times had he pushed himself to the point of no return, to the brink of bankruptcy and destitution? Was he testing those around him to see whether they would bail him out? Was he acting out a lifelong destructive impulse rooted in a sense of self-hatred?

++

My mother has also made promises regarding the disposition of her assets, though these promises have never filled me with expectation or hope. For years, ever since I left California for college, she threatened to adopt another child. “Be careful,” she’d say. “If you’re not a good son to me, I adopt myself one of these little Guatemalan girls.” In the end, she didn’t adopt a girl from Guatemala—she adopted a five-year-old Russian boy. Alosha was born with severely deformed legs and he spent the first years of his life in an orphanage. A few years after she adopted him, after he had his legs amputated, she told me she’d changed her will to make Alosha the nearly sole beneficiary. “You don’t need my money,” she declared. “You’re educated, you have a good life.”

She was right. I had a J.D. and a job, and even if I didn’t love being a lawyer, I could always support myself. In many ways, her decision made sense. Still, the way she delivered the news didn’t feel right—she said it in front of Alosha with a smile on her face. What she was really saying was, You’ve been a bad son; you don’t love me; I’ve adopted a child who will give me what you have withheld. When I die, he’ll inherit the money I’ve saved.

I told her I understood. I acted like it didn’t matter to me. I acted like I didn’t care what she did with her money.

Since then, Alosha has grown into an impressive young man. He’s articulate and thoughtful and, in 2014, he moved to Berkeley for college. He hasn’t turned out to be the doting son my mother hoped for, however, and sometimes it seems she’s as disappointed with him as she is with me. Last fall, a relative told me my mom was considering changing her will yet again and making her nieces in Germany the primary beneficiaries. I have no idea whether she made the change. I’ve lost track. At one point, when the topic of her will came up, she told me she’d put me back in; later, she said she might leave everything to the Music Academy or the Humane Society.

++

Growing up, I learned that money was love—that money given was love bestowed; that money withheld was love denied, or, in some cases, retribution; that money was power; that money was obligation, that a gift (cash or otherwise) would have to be repaid in one form or another, that it came with strings attached, that accepting it was not without risk; that money was something to hoard and tally and track; that a man who shelled out $5.99 for pizza expected sex in return; that a woman who cooked a meal for a suitor and let him make love to her should be given flowers or perfume or a new dress; that a woman with a rainy day fund was stronger and more self-sufficient than a woman without money in the bank; that a widow with savings and a pension and rent-producing properties would never again go to bed hungry or live in a one-room hut in the mountains or have shoes that were too small for her feet.

When my father lost his temper, then gave me a silver dollar or took me out for coq au vin, it was his way of apologizing, of making me feel close to him again, of persuading me to let down my guard. When, for my thirtieth birthday, he sent me an envelope with thirty one hundred dollar bills, what he was trying to say is I may not have always been the best father, but I’m proud of you. I love you and hope you’ll forgive me.

When I was twenty-three and sent my mother a framed photo of me as a Christmas gift, she refused to return my calls for several weeks. She told me it was the worst present she’d ever received. Yes, she was angry I didn’t spend Christmas with her, but she was also offended I hadn’t spent more on her gift.

Some years, when my mother and I are getting along and she feels secure that I do in fact love her, she’ll write me a check to pay for my trip to California. A few years ago, she sent me a check for twenty-thousand dollars. “I have plenty of money,” she said. “I don’t need it. You need it more than I do.”

I was dumbstruck. For decades, she’d promised me large sums of money, but she’d never actually kept her word. In my twenties, when I was first living in New York, she promised to buy me an apartment. She flew to New York and asked a real estate agent to take us around the city to look at one bedrooms on the Upper West Side, then she changed her mind. “You’re so young,” she said. “Who knows if you even will stay in New York. Let’s buy you something when you’re settled down.” When I decided to go to law school, she told me she would cover the tuition. “Your father paid for your college. I want to do something for you. I can afford it. I’m loaded.” She changed her mind about that too, and I took out $96,000 in loans. Last year, when my partner, Stan, and I were buying an apartment together, she promised another sum of money—a large sum. “But if I give this to you, you have to promise me I can stay with you when I visit.”

I told her she could stay with us. I told her I couldn’t believe she was actually going to give me that much money. “Of course, I give it to you,” she said. “I’m selling the place in Idaho. I’m getting $550,000. What am I going to do with it? Put it in the bank? What good does it do in the bank? I want you to be happy. You’re my son.”

In the end, she changed her mind, deciding instead to buy another house in Santa Barbara. When I visited her for Christmas, she drove me to the house. “What’s this?” I asked when she opened the front door.

“It’s your house,” she announced. “I bought it for you.”

I wasn’t sure what she meant.

“I bought it for you and Stan so you have someplace to retire.”

I stared at her, still perplexed.

“Isn’t it beautiful? You always complain about how much you hate the Goleta place. It’s so you can come here and retire when you’re sick of New York.”

“But I’m only fifty. Stan’s forty-five. We’re not retiring.”

“I know, I know,” she said, “but in the future, you’ll have someplace to live. It’s for you and Alosha. This is why I couldn’t give you the money I promised. It was a very good deal. I got it for one million, one hundred thousand. I talked them down from one three. It was a steal.”

Some people might be thrilled to find out their mother had bought them a house—even if it was three thousand miles away. I’d been down this road before, however. I knew there was a catch. There was always a catch. It didn’t surprise me when I learned the title of the house remained in my mother’s name and that she’d already rented it out to an acquaintance. Nor did it surprise me later to hear her complain about the renter, or, more recently, to learn she was putting the house on the market, never acknowledging the fact that it supposedly belonged to Alosha and me.

++

Sadly, my mother and I fight about everything. We can’t help it.

When I was younger, we fought over her insistence on letting the dog eat off our plates. We fought over her letting the dog defecate on neighbors’ lawns. We battled over how much butter and sour cream she put in the food she prepared. Nowadays, we argue about how many days I will visit her. We bicker about the fact that she puts carpet remnants, tennis balls, and dead leaves into the recycling bin labeled PAPER AND CARDBOARD, about the fact that she throws dog feces and ripped underwear into the bin for PLASTIC AND GLASS. We squabble about how she’s too cheap to pay for the city to pick up her garbage, that instead of paying for two garbage bins, she only pays for one, using the recycling containers for her excess trash.

Often, the fights stem from our different attitudes toward money. I am by no means a spendthrift, but I’m picky about what I eat, and when I visit her I insist on shopping at Whole Foods. I buy organic apples and strawberries. I buy grilled tofu and broccoli rabe from the salad bar. She watches me shop, dumbfounded, and when we reach the cashier she sometimes reaches into her purse, offering to pay for the groceries.

“You don’t have to pay,” I tell her. “I can pay.”

“No, you’re my son, you’re visiting me. Of course, I pay.”

Sometimes, I let her pay, though she’ll invariably remind me how much she spent. If we run into someone she knows, she’ll complain about the cost of the groceries. “It’s incredible how much this place charges. Three dollars a pound for apples. I can get them at Ralphs for ninety-nine cents!”

Usually, I’ll tell her to give it a rest. “You always do this,” I’ll grouse. “I told you I could pay.”

“I’m not complaining. I just don’t understand why you have to shop at such an expensive store. I have plenty of food at home. What’s wrong with my food? Why is it not good enough? You’re just like your father. You inherited his expensive taste.”

But I’m not just like my father. I earn a paycheck. I have savings. In fact, the older I get, the more I’m struck by how similar I am to my mother. Recently, I’ve begun squirreling away plastic bags and partially-used paper towels. Just last week, Stan opened one of the drawers in our kitchen and asked me why there were so many crumpled-up napkins and partially-used sheets of Bounty in the drawer. “I don’t know,” I told him. “In case we need to wipe out some sauce from a container or something. I don’t want to use a new paper towel for that.”

I care about the environment, but the truth is I can also be cheap. Hard as it is to admit, that’s not the only trait I share with my mother. I’ve also become adept at keeping the same kind of financial tally she’s always kept: I paid $120 for her Christmas present, but she only bought me something for eighty dollars. I paid for my friend’s movie ticket last month; he still “owes” me fifteen bucks; I didn’t order wine with my meal—should we really split the bill evenly?

I don’t get the same high out of saving money as my mother (or spending like my father), but I think about money a lot. I keep track of how much money I’ve saved. I pay attention to how much things cost. And, like my mother, it’s always been important for me to keep my finances separate from Stan’s. He and I have been together since 1999, and I have no doubt we’ll stay together for the rest of our lives, but part of me continues to see my wellbeing as tied to my savings. Like my mother, I sleep better knowing I have money in the bank—money that no one else will be able to touch.

Stan wasn’t raised to worry about money. His parents never talked about their salaries or bills or how much they had in their checking account. They never used money as a tool to manipulate or cajole, to mete out punishments and rewards. Not surprisingly, he shares none of my hang-ups. Even when he and I were younger and had no savings at all, he didn’t fret about the future, didn’t think twice about paying for a taxi or a nice meal out.

I didn’t grow up during the war with nothing to eat. Still, it’s only in the past few years that I’ve genuinely been able to stop keeping track of finances with the person who means more to me than anyone else in the world, the one person who has, since the moment I met him, been honest and caring and dependable; the person who has proved, again and again, that he will always be there for me, will never try to cheat me or take advantage or make me feel guilty when he does something kind. Why is it that the lessons we learn as children are so hard to unlearn? Why is it that, after nineteen years, I still need to keep my savings separate from my soulmate’s assets?

++

Tomorrow is my birthday. Today, when I checked the mail, I received a birthday card from my mother. Inside was a check for $150 for me and a check for $340 for a charity called World Vision. Her note included the following explanation:

I was very impressed that Alosha wanted to have his friends and you giving money to urgent relief. [For his birthday, he’d asked people on Facebook to contribute to Unidos Por Puerto Rico.] I feel the same way and give in your name money where it is urgently needed. Why should we be living in luxury just because we were dealt a better hand than they are?

She included an envelope addressed to World Vision and asked me to send the $340 check to them. She also included a few photos of African children making baskets and bracelets.

Since opening her card, I’ve spent a considerable amount of time—a ridiculous amount of time—trying to figure out what the checks mean. I guess this isn’t surprising, given that I’ve spent my entire life interpreting the gifts I’ve received from my parents. What does it mean for my mother to send me a check for $150? On the one hand, I don’t need her money. On the other hand, this is a woman who, at times, has sent me checks for $1,000 or more just because. Why send me this relatively small amount for my birthday, an occasion to which I know she attaches great significance?

Is it simply a function of the fact that she’s had some unexpected bills? Is she signaling that she feels neglected, that she’s angry I haven’t visited her for nearly twelve months? And why include the check for World Vision? Is she letting me know that her gift is more than just the $150, that she is in fact being quite generous? Or is she signaling that she has plenty of money and is indeed trying to punish me? In the past, when she’s sent me gifts of relatively small amounts, she’s admitted later that she was angry with me. Is this another of these occasions? I’m turning fifty-one years old. Why am I still worrying about how much my mother sends for my birthday? Why can’t I break this dysfunctional dance we established so long ago?

Maybe I’ll never understand my parents. Maybe all I’ll ever have is my imprecise and increasingly unreliable memory of things that have happened and the snippets of conversations that may or may not have taken place. Maybe I’ll never understand what it was like for my mother to grow up during the war, never understand why she breaks down in tears so often, at life’s smallest setback; why she meets someone at the tennis courts and throws herself headlong into the friendship, then calls me up, crying, telling me the person betrayed her; why she makes promises she doesn’t keep. Maybe I’ll never understand why someone who complains about spending three dollars a pound on organic apples can impulsively decide to spend two grand on beauty products in Las Vegas. Or why someone who complains about the length of her renter’s showers can give the same man $1,250 to help fix his car.

Maybe I’ll never know what caused my father to call people cocksucker when he was on the freeway, going seventy, eighty, ninety miles an hour and telling me not to be a mama’s boy when I pleaded with him to slow down; why someone who could be so angry and violent could also be compassionate enough to stop on the street in Santa Fe and hand a Native American woman or a homeless person sitting on the sidewalk all the cash in his wallet.

More than a few of my friends have suggested that perhaps one or both of my parents might suffer (or have suffered, in the case of my father) from undiagnosed depression or borderline personality disorder. My father did, my mother does, exhibit some of the hallmark traits of BPD: mood swings, lack of boundaries, loneliness, unstable relationships, impulsiveness, suicidal ideation. But maybe there wasn’t anything wrong with my father. Maybe his behavior can be attributed, as he always claimed, to the fact that his mother was distant during his childhood. Maybe he spent his life simply searching for someone to love him. Maybe my mother was simply traumatized by the war, by living on the precipice of starvation, deprivation, and death. I wonder about my use of that word: simply. How dare I call these things simple?

Maybe the reason I’m half a century old and still writing essays and poems and stories about my parents is that something is wrong with me. Why is it that I can’t let go of the past and move on? Why do I keep my money separate from the person I love most in the world? Why is it that this Christmas and next Christmas and the following Christmas I will register how much my mother spends on the presents she gives me? Why will I keep a mental record of how much I spend on the gifts I buy her and how much I spend on my plane ticket and rental car? How long will I keep doing all this unhealthy math? When will I finally rip up the tally and throw the toxic scraps of paper away?

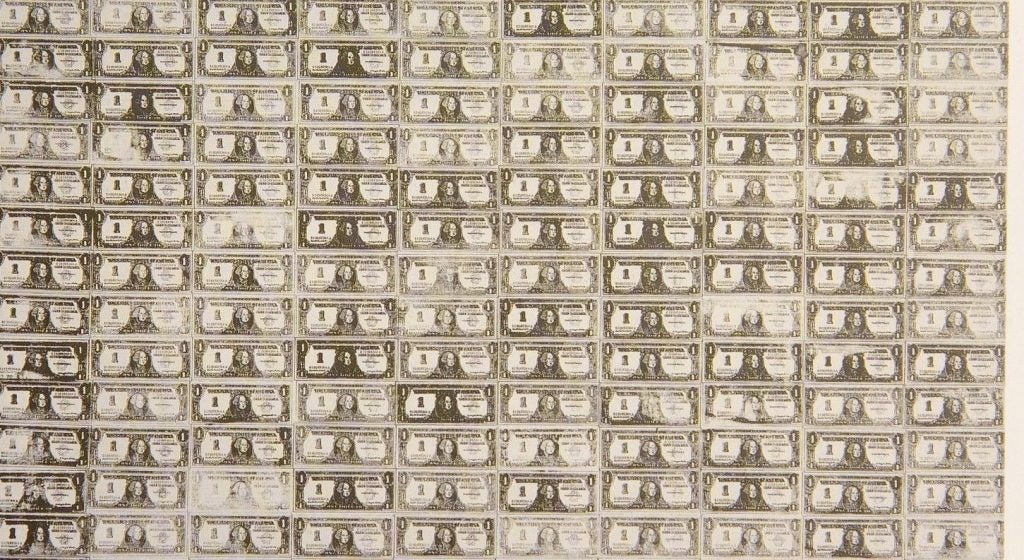

Image: Warhol, Andy. “200 One Dollar Bills.” 1962. Acrylic on canvas. Private collection.

Image: Warhol, Andy. “200 One Dollar Bills.” 1962. Acrylic on canvas. Private collection.

Matthew Lansburgh’s collection of linked stories, Outside Is the Ocean, won the 2017 Iowa Short Fiction Award and was a finalist for the 30th Annual Lambda Literary Award and the 2018 Ferro-Grumley Award for LGBTQ Fiction. His fiction has appeared in Glimmer Train, Ecotone, Electric Literature, StoryQuarterly, Guernica, Michigan Quarterly Review, Columbia Journal, The Florida Review, and Joyland. In selecting Outside Is the Ocean as the winner of the Iowa Short Fiction Award, Andre Dubus III described the book as “mesmerizing.” You can visit Matthew online at matthewlansburgh.com.