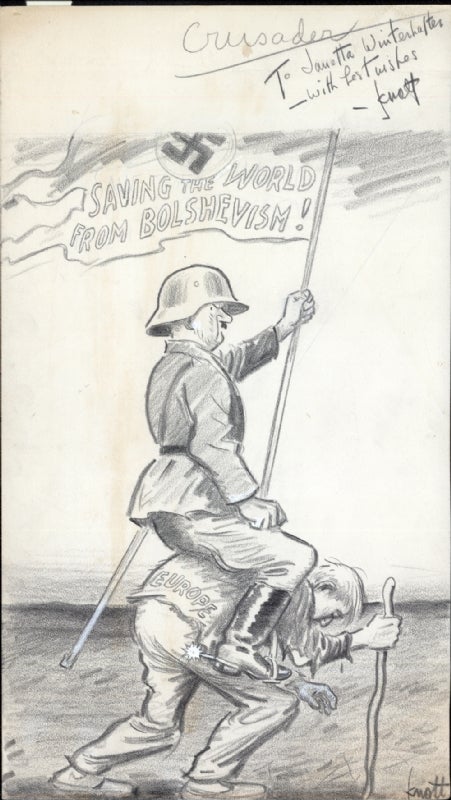

“Crusader” (October 28, 1941)

by John Francis Knott (1878 – 1963)

8 x 16 in., pencil on board

Coppola Collection

Knott started working at the Dallas News as an artist in 1905 and achieved national prominence for his World War I and Woodrow Wilson era cartoons. He had a 50-year career with the Dallas News and created more than 50,000 cartoons. Texas newspapers widely acknowledged that Knott helped increase the sales of Liberty Bonds and donations to agencies involved in the war effort.

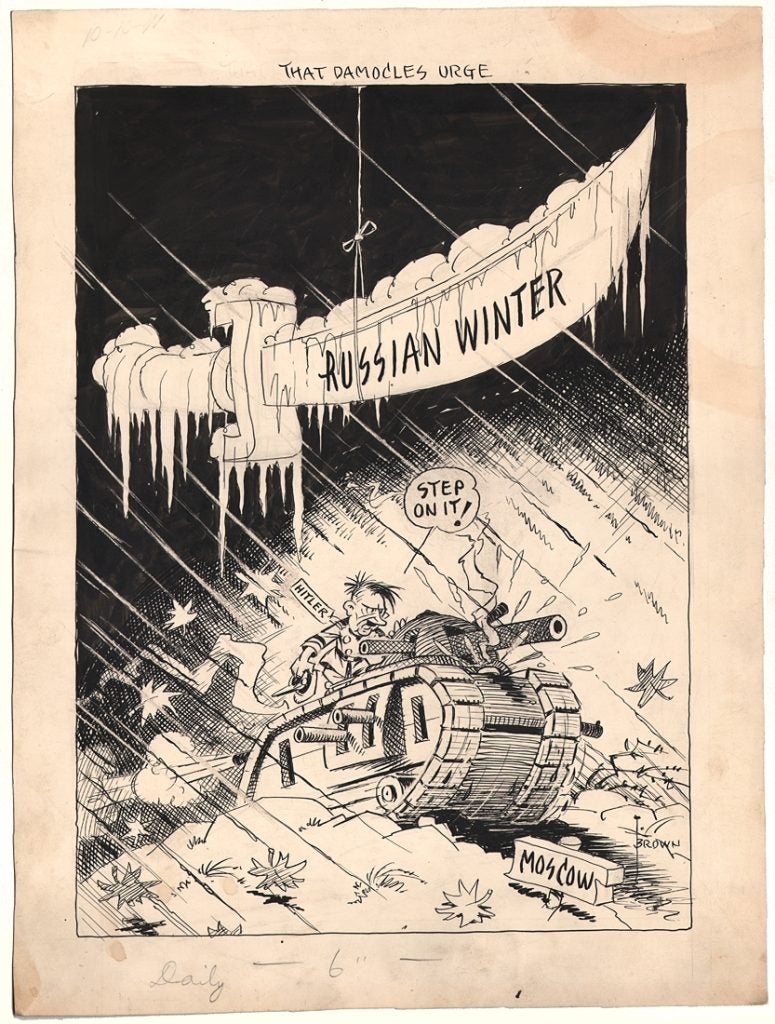

By mid-1941, the Nazis were moving into the Soviet Union from Europe (Operation Barbarossa, June 22, 1941). Here is an excerpt from two speeches given in late 1941 and early 1942 that specifically mention protecting Europe from Bolshevism:

“Didn’t the world see, carried on right into the Middle Ages, the same old system of martyrs, tortures, faggots? Of old, it was in the name of Christianity. To-day, it’s in the name of Bolshevism. Yesterday, the instigator was Saul: the instigator to-day, Mardochai. Saul has changed into St. Paul, and Mardochai into Karl Marx. By exterminating this pest [Bolshevism], we shall do humanity a service of which our soldiers can have no idea.”

21 October 1941

But I think that if Providence has already disposed that I can do what must be done according to the inscrutable will of the Providence, then I can at least just ask Providence to entrust to me the burden of this war, to load it on me…. Thus the home-front need not be warned, and the prayer of this priest of the devil, the wish that Europe may be punished with Bolshevism, will not be fulfilled, but rather that the prayer may be fulfilled: “Lord God, give us the strength that we may retain our liberty for our children and our children’s children, not only for ourselves but also for the other peoples of Europe, for this is a war which we all wage, this time, not for our German people alone, it is a war for all of Europe and with it, in the long run, for all of mankind.”

Speech in Berlin 30 January 1942