“War! War!” (June 13, 1940)

by Emidio (Mike) Angelo (1903-1990)

18 x 18 in., ink on art board

Emidio Angelo was born in Philadelphia, a year after his mother and father, a baker, arrived from Italy. He studied art from 1924 to 1928 at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Angelo joined The Philadelphia Inquirer as a political cartoonist in 1937 and worked there until 1954. He also drew cartoons for the Saturday Evening Post, Life and Esquire.

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. And less than a year later, both sides (but especially the Germans) were set to escalate past The Phoney War. Germany invades the West on May 10, 1940, taking the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg. This was the day British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain resigned and was replaced by Winston Churchill. In six weeks time, Hitler would be walking through the streets of Paris.

On June 8, 1940, the Germans crossed the Seine.

On June 9, 1940, the French government fled Paris.

On June 10, Norway surrendered to Germany.

On the evening of June 10, 1940, Benito Mussolini appeared on the balcony of the Palazzo Venezia to announce that in six hours, Italy would be in a state of war with France and Britain.

“People of Italy: take up your weapons and show your tenacity, your courage and your valor.”

The Italians had no battle plans of any kind prepared. Anti-Italian riots broke out in major cities across the United Kingdom after Italy’s declaration of war. Bricks, stones and bottles were thrown through the windows of Italian-owned shops, and 100 arrests were made in Edinburgh alone. Canada declared war on Italy. Italy broke off relations with Poland. Belgium broke off relations with Italy. And the Italian invasion of France began.

While making a commencement speech at the Memorial Gymnasium of the University of Virginia, President Roosevelt denounced Mussolini: “On this tenth day of June, 1940, the hand that held the dagger has plunged it into the back of its neighbor.” The president also said that military victories for the “gods of force and hate” were a threat to all democracies in the western world and that America could no longer pretend to be a “lone island in a world of force.”

On June 14, the Germans entered Paris unopposed (and as every fan of Casablanca knows, Ilsa Lund left Rick Blaine a goodbye note as he boarded the train to Marseille, on the way to North Africa).

On June 23, 1940, Adolf Hitler took a train to Paris and visited sites including the Eiffel Tower, the Arc de Triomphe and Napoleon’s tomb.

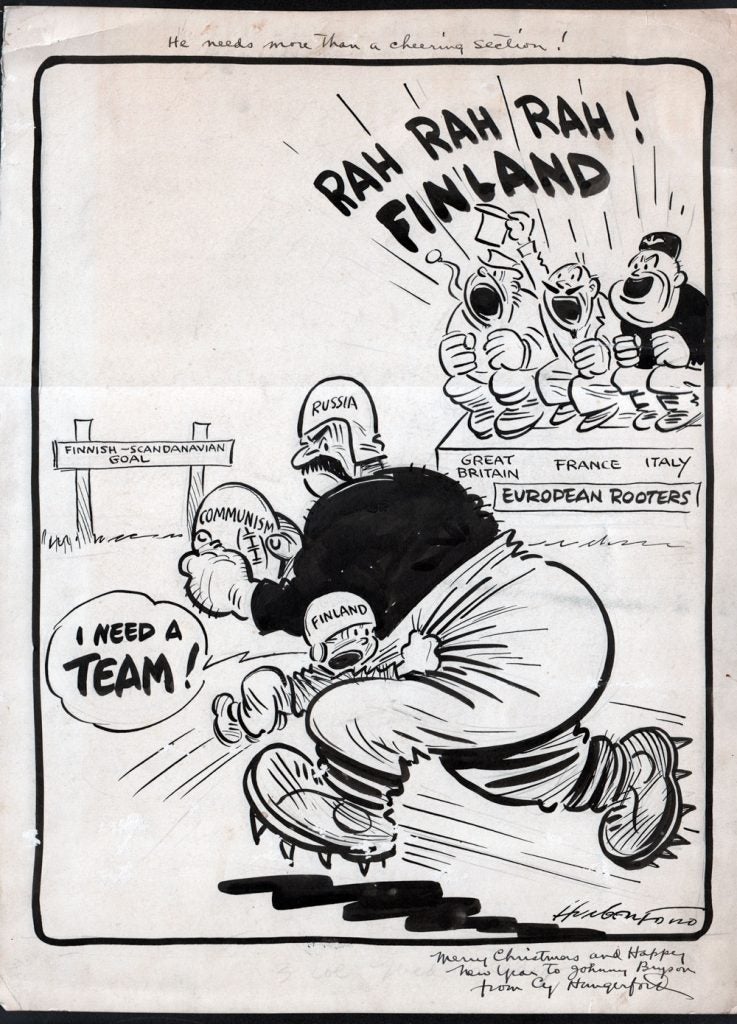

“He Needs More Than A Cheering Section” (February 5, 1940)

“He Needs More Than A Cheering Section” (February 5, 1940)