“What a Handy Article an Umbrella Is” (September 30, 1938)

by Vaughn Richard Shoemaker (1902-1991)

22 x 24 in., ink on paper

Coppola Collection

Vaughn Richard Shoemaker was an American editorial cartoonist. He won the 1938 and 1947 Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning and created the character John Q. Public.

Shoemaker started his career at the Chicago Daily News and spent 22 years there. His 1938 Pulitzer cartoon for the paper was “The Road Back”, featuring a World War I soldier marching back to war. The 1947 winning cartoon for the paper was “Still Racing His Shadow”, featuring “new wage demands” of workers trying to outrun his shadow “cost of living”. He went on to work for the New York Herald Tribune, the Chicago American, and Chicago Today. By his 1972 retirement he had drawn over 14,000 cartoons.

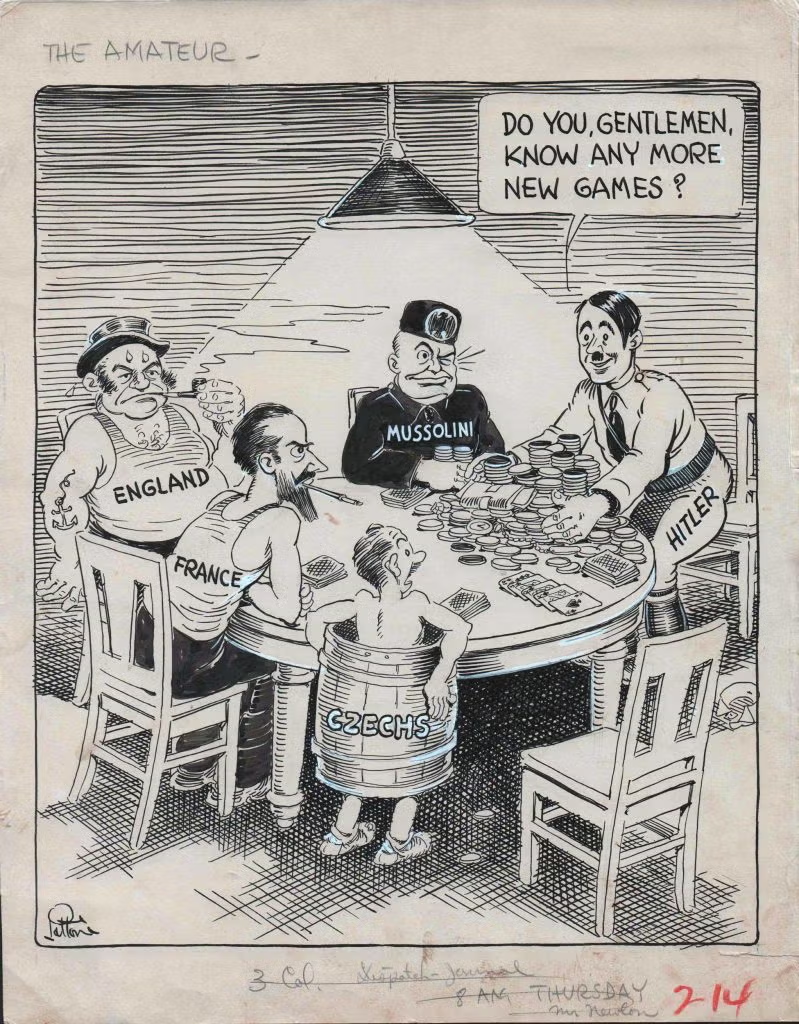

In 1938, Shoemaker won the first of two Pulitzer Prizes for Editorial Cartooning. This cartoon is fairly self-explanatory. And I have covered the reasonable background for it previously, so let’s fire up the way-back machine and self-plagiarize a bit. This cartoon related to the famous “peace for our time” speech that the British PM, Chamberlain, gave upon return from Germany…

Historians report that the Treaty of Versailles (1919), brokering the peace at the end of WWI, caused significant resentment in Germany, and that Hitler played off of this to achieve power. The British government believed that Hitler and Germany had some genuine grievances, but that if these could be met (‘appeased’) Hitler would be satisfied and become less demanding.

Becoming Chancellor in 1933, Hitler began to re-arm the country, breaking the Versailles restrictions. In March 1938, he annexed Austria. Czechoslovakia was next.

The story of the cartoon tells it all. In September 1938, British PM Neville Chamberlain returned from Germany, having signed the Munich Agreement as an appeasement, allowing Hitler to subdivide Czechoslovakia, and then famously, publicly, and ultimately ironically declared “My good friends, for the second time in our history, a British Prime Minister has returned from Germany bringing peace with honor. I believe it is peace for our time.”

German forces moved in and occupied a significant chunk of Czechoslovakia on October 1. Six months later, all of Czechoslovakia was taken over. Poland was next.

Digging into this a little more: after WWI, the European League of Nations was set up to create a mechanism of cooperation and communication, in an attempt to circumvent another war. The rise of Hitler and Mussolini, and their build-up of military conflict, proved that the League was not particularly effective.

Late in the 1930s, the major European nations adopted a policy of “appeasement,” in which concessions were granted to these two dictators with the idea that they would be satisfied and agree not to escalate their aggression. British PM Chamberlain, who took office in 1937, continued the policy.

Czechoslovakia was made up of a patchwork of territories, including a region with a majority German population called Sudetenland. The Sudeten Nazis, and Hitler, were emphatic about Sudeten’s autonomy from Czechoslovakia.

By September, 1938, violence was increasing as Hitler and the Nazis agitated against Czechoslovakia. Chamberlain made two trips to Germany in September.

By now, Hitler was demanding the ‘return’ of Sudetenland to the Empire under threat of a new war. During the first trip, Chamberlain agreed to advocate for handing over Sudetenland to Germany. And in response, Hitler continued to escalate attacks on Czechoslovakia. A week later, after the second trip, where Chamberlain agreed to Germany’s possession of the Sudetenland, Hitler upped the ante, insisting that Czechoslovakia be broken up completely… a demand he dialed back in exchange for the unconditional separation and return of the Sudetenland by October 1.

This appeasement, called the Munich Agreement, was the basis of Chamberlain’s declaration of peace on the same day as the publication of this cartoon, giving us all (today) an interesting sense of just how up to date communication, attention, and opinion was about current happenings. This cartoon is viable for only about a day – between Chamberlain’s declaration on September 30…

“I believe it is peace for our time. Go home and get a nice quiet sleep.”

… and the Nazi invasion of Sudetenland on October 1.

“Neville Chamberlain’s umbrella” turns out to be as big a deal as “Hilter’s moustasche” or “Churchill’s cigars” in terms of symbolism. After the Munich Agreement, Chamberlain become known as the Umbrella Man.

A recent article on Chamberlain and the umbrella sheds light on all of this.

Quoting from there:

Due to the irrefutable diplomatic failure of the Munich Agreement signed on 30 September 1938, at each juncture in the reassessment of appeasement historians, political scientists, and generations of politicians too have tried to identify the underlying lesson to be learned, whether strategic, ethical, or psychological. Munich has consistently been conjured as an object lesson in international relations, an example of a how negotiations with dictators should not be conducted, and used to serve as a practical example of a principle or an abstract idea.

In fact, umbrellas, and Chamberlain’s umbrella in particular, were omnipresent in the visual and material culture, and in the rhetorical constructions of the Munich Crisis and in its aftermath. Chamberlain’s umbrella was easily the most produced and reproduced political emblem of late 1938–9, represented in a wide range of textual and visual forms in the media, and in consumable forms as accessories, adornments, novelties, souvenirs and edible delicacies. In Britain and abroad, and especially in France, the umbrella came to stand for a distinctly British form of diplomatic engagement. The Yorkshire Post asked: ‘Is there any other single object that could be turned to so much political symbolism? Perhaps it was the association of ideas between Mr Chamberlain’s mission and the purpose of the umbrella that struck foreign imagination…the umbrella has no bellicose connotations. It is shelter, protection (originally against sun as well as rain)’.