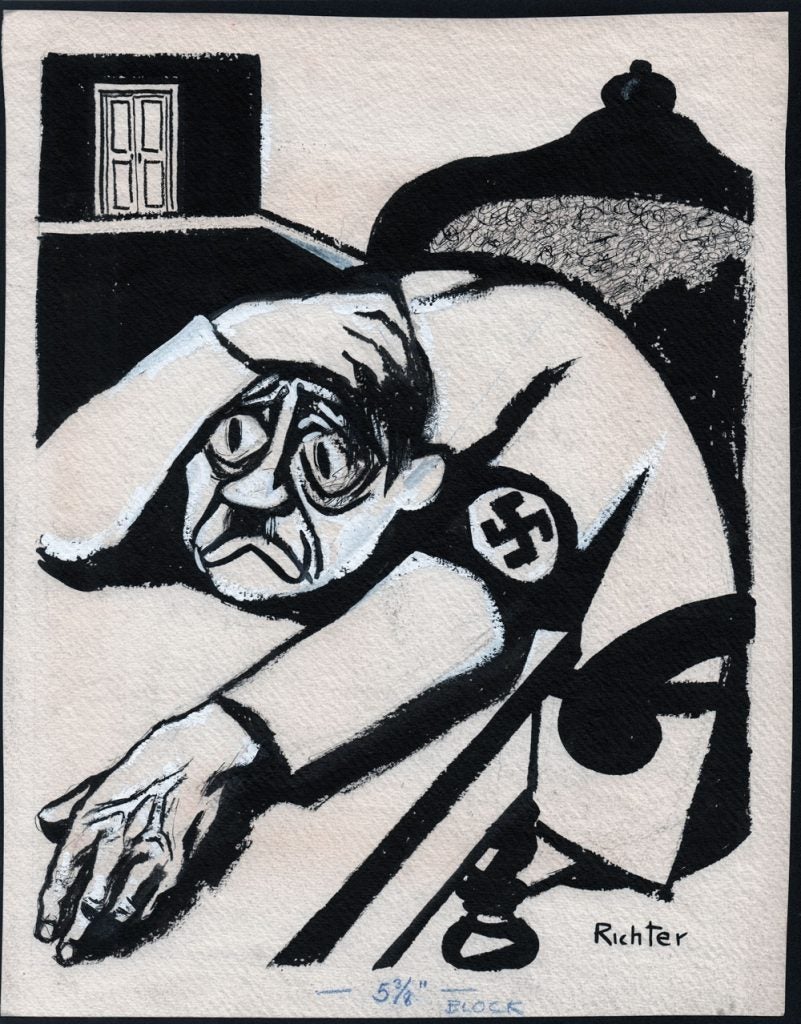

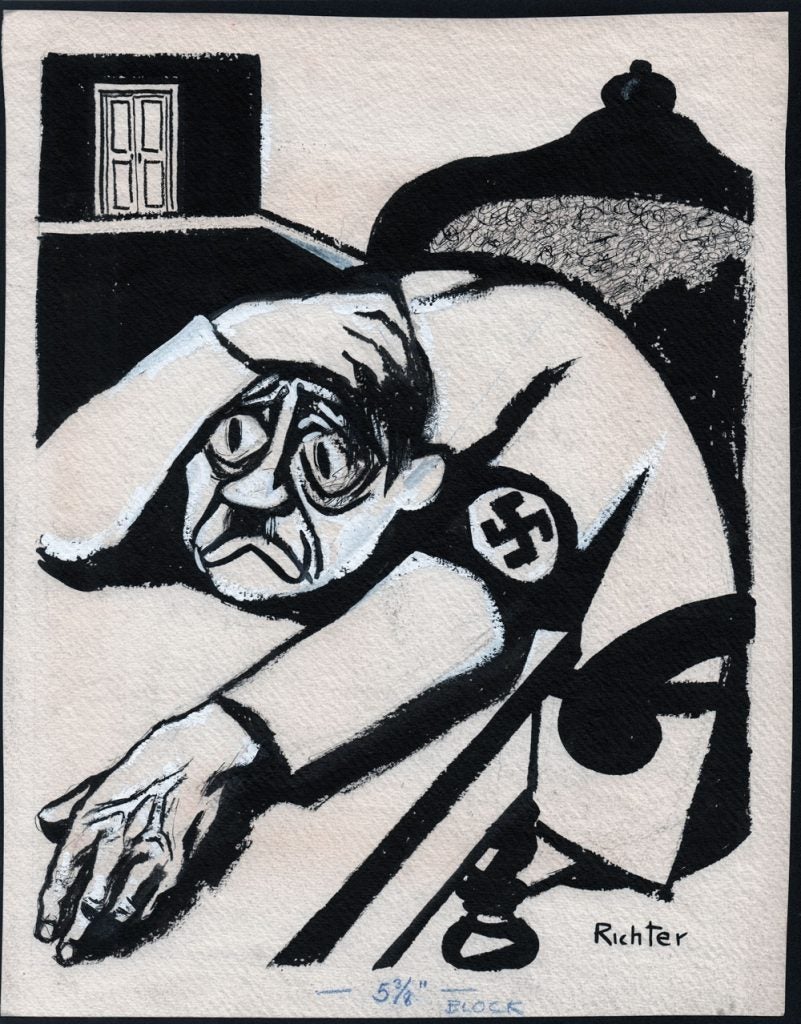

“If only Vincent Sheean could persuade the Czechs…” (November 28, 1939)

by Mischa Richter (1910-2001)

10 x 14 in., ink and wash on paper

Coppola Collection

November 1939 is less than three months after the Nazi invasion of Poland (September 1) that marks the start of WW2. This is not a drawing of the historical Hitler, monstrous with the insight of hindsight. To many in 1939, he is an authoritarian despot with still-secret ambition for world conquest, benefitting from the surprising non-aggression pact with Stalin (Molotov-Ribbentrop Treaty, August 1939), the appeasement policy of British PM Chamberlain (“peace for our time”), and the radical isolationism of the US after WW1.

A despondent Hitler splays across a table and wonders “If only Vincent Sheean could persuade the Czechs that Communism and fascism are the same thing.”

Who is Vincent Sheean, and what is happening in Czechoslovakia?

In 1918, Vincent Sheean joined the Army with the intention of taking part in WW1, which ended before he served. He lived in Greenwich Village with left-wing figures who had reported on the 1917 Russian Revolution and the civil war that resulted in the rise of communism and the establishment of the USSR in 1923. In 1922 he visited Europe, settling in Paris where he became foreign correspondent.

Sheean published his autobiographical Personal History in 1935. The book tells the story of Sheean’s experiences of reporting on the rise of fascism in Europe. Sheean was highly critical of both Chamberlain and the US. His follow-up book, Not Peace but the Sword was published in March 1939, the same month that Czechoslovakia was invaded, and it was on the bookstands as a bestseller only weeks before the invasion of Poland on September 1. Both books focus on the rise of fascism in Germany, its parallel and at least sympathetic relationship with communism, and what he saw as a betrayal by England and France to not defend democracy more strongly.

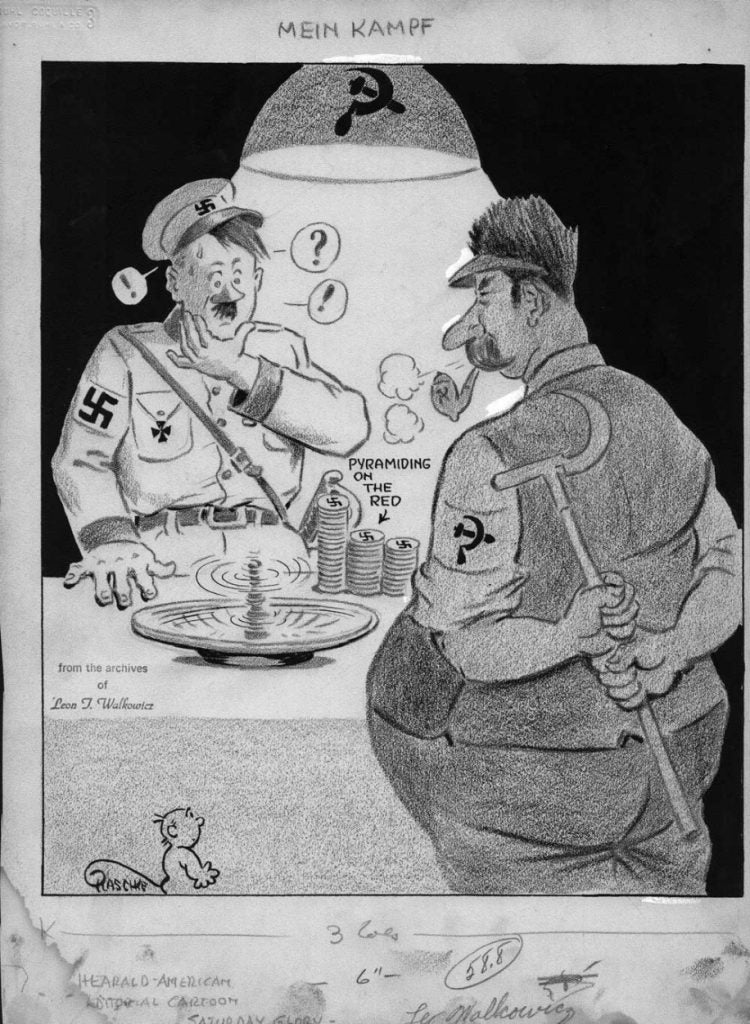

Hitler annexed all of Austria without firing a single shot in March 1938. His next target, as had been laid out in Mein Kampf, was the possession of the Sudetenland, the part of Czechoslovakia where millions of ethnic Germans lived.

Journalists rushed into Prague, capital city of the Czech Republic, to report on the drama that unfolded over the following months. Among those who came to observe and report: Vincent Sheean. Sheean reported on September 21, 1938, having spent the day in the Sudetenland, that loud speakers posted throughout the city had just announced to the Czechs that under pressure from London and Paris, the government had accepted the German dictator’s demand for a revision of the two countries’ border.

Chamberlain (September 1938): “My good friends, for the second time in our history, a British Prime Minister has returned from Germany bringing peace with honour. I believe it is peace for our time.”

Chamberlain is frequently misquoted as “peace in our time.”

On March 15, Hitler threatened a bombing raid against Prague unless he got free passage for German troops into Czech borders. He got it. By evening, Hitler made his entry into Prague.

Another easy conquest, with the stage set for his move on Poland. The secret terms of the August 30, 1939 non-aggression pact with Stalin (Molotov-Ribbentrop Treaty) outlined how Czechoslovakia and Poland would be divided between Germany and Russia, giving the Nazis their opening to invade Poland.

Hitler bamboozles England and France with promises of peace. On October 28, thousands of people, mainly students, mark the 21st anniversary of the founding of Czechoslovakia. The Nazis retaliate by closing universities, executing student leaders and making arrests. On November 17, Germans attacked and arrested thousands of students, sending many to concentration camps. Nazis executed nine Czechs by firing squad without trial for leading the demonstrations. On November 18, the Nazis closed all the technical schools.

Today, International Students’ Day is observed on November 17. The year 2019 marks the 80th anniversary.

Richter’s cartoon expresses anxiety by Hitler on how things are going in Czechoslovakia. It might have looked like he was getting pushback from the Czechs, but we know in retrospect that the Nazis had the situation in hand.

And 2019 is also the 80th anniversary of Marvel comics (Marvel Comics #1 was published in October 1939). In the 2015 movie, Age of Ultron, Tony Stark explicitly and ironically uses the “peace in our time” phrase as something that could now be possible, as it was not before, because of the protective Ultron protocol he wants to put in place around the earth following the alien invasion seen in the first Avengers movie. Stark’s dialog: “peace in our time, imagine that.” His naïve arrogance inspires the now-sentient Ultron to repeat the quote, which is played back after Ultron takes a look at the madness of human history, as a mandate to exterminate human life as the only pathway to peace.