“The Butcher’s Helper” (December 29, 1937)

By Stan MacGovern (1903-1975)

12 x 14 in., pen on paper

MacGovern was best known for his comic strip “Silly Milly” which ran in the New York Post from the 1930s into the 1950s. McGovern also drew editorial cartoons for the Post, and he was included in a 2004 exhibit, “Cartoonists Against the Holocaust: Art in the Service of Humanity,” sponsored by the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies. Silly Milly, which had limited syndication, came to an end in 1951. MacGovern left the newspaper field to run a gift shop on Long Island. It was an unsuccessful business, and he later worked at a Long Island furniture store. In 1975, at the age of 72, he committed suicide.

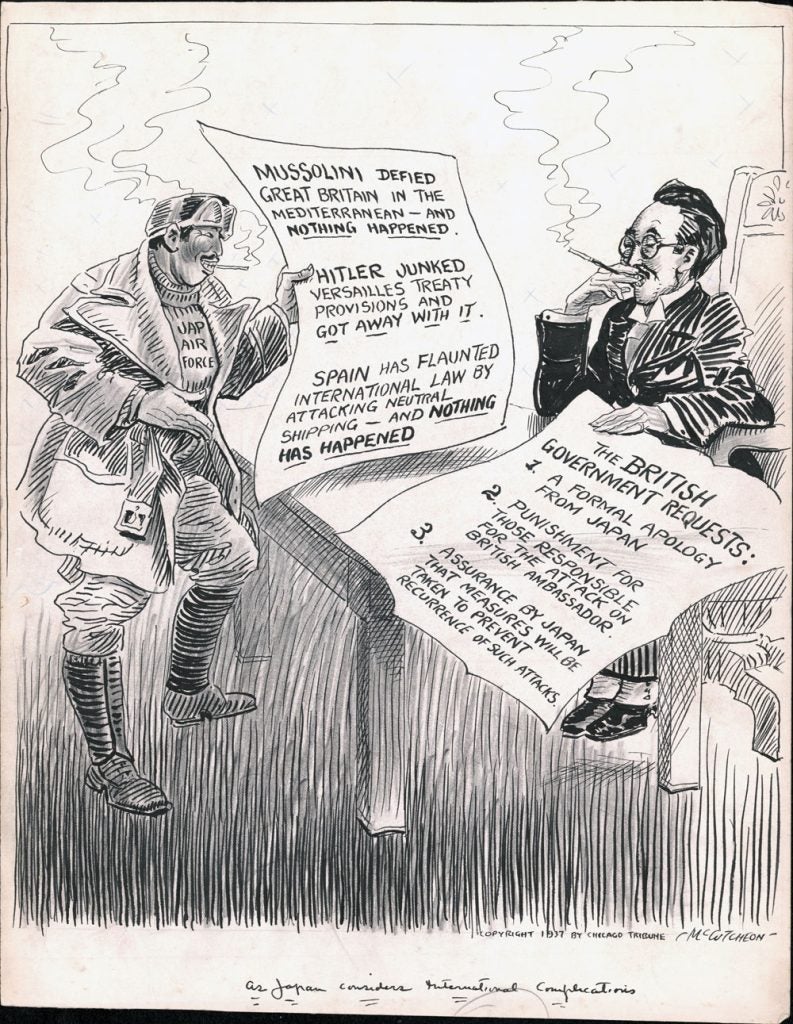

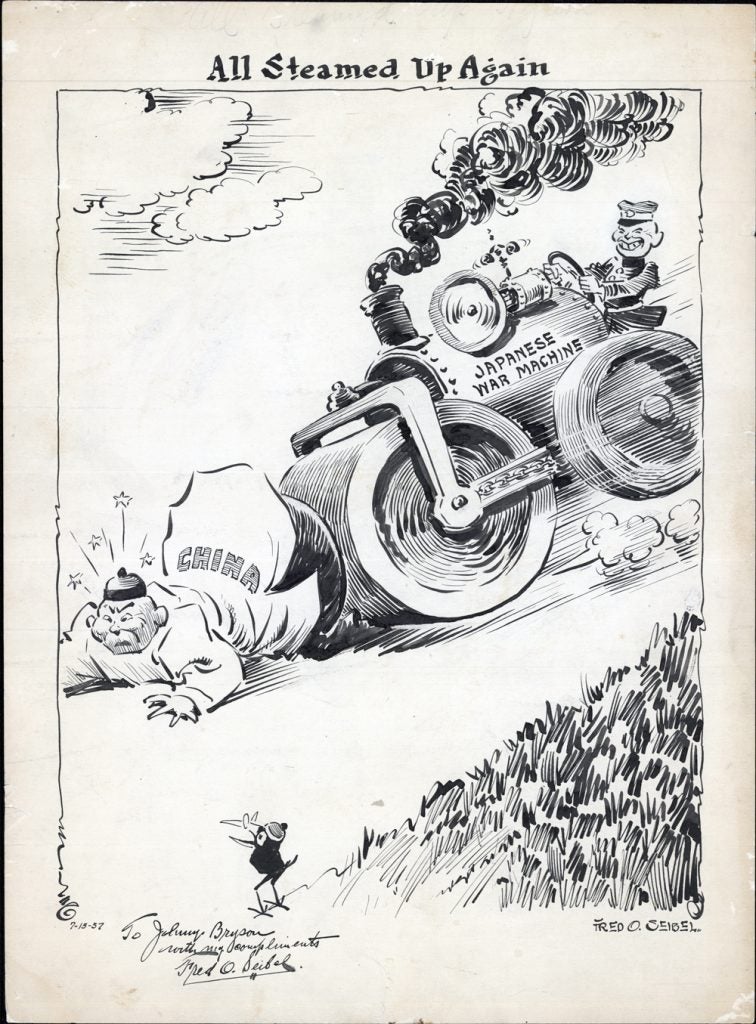

Between 1937 and 1941, escalating conflict between China and Japan influenced US relations with both nations, and ultimately contributed to pushing the United States toward full-scale war with Japan and Germany.

At the outset, US officials viewed developments in China with ambivalence. On the one hand, they opposed Japanese incursions into northeast China and the rise of Japanese militarism in the area, in part because of their sense of a longstanding friendship with China. On the other hand, most US officials believed that it had no vital interests in China worth going to war over with Japan. Moreover, the domestic conflict between Chinese Nationalists and Communists left US policymakers uncertain of success in aiding such an internally divided nation. As a result, few US officials recommended taking a strong stance prior to 1937, and so the United States did little to help China for fear of provoking Japan.

US likelihood of providing aid to China increased after July 7, 1937, when Chinese and Japanese forces clashed on the Marco Polo Bridge near Beijing, throwing the two nations into a full-scale war. As the United States watched Japanese forces sweep down the coast and then into the capital of Nanjing, popular opinion swung firmly in favor of the Chinese. American outrage with Japan rose when the Japanese Army bombed the USS Panay on December 12, 1937, as it evacuated American citizens from Nanjing, killing three, and for the reports of the atrocities of the Nanjing Massacre. The US Government, however, continued to avoid conflict and accepted an apology and indemnity from the Japanese on Christmas eve.

There is nothing too subtle about the message, here. It’s unusual to see political editorials in this era that are so openly critical of the US in this way. The common criticism around this time was from the anti-isolationists who depicted the US with indifference to outright defiance for not getting involved with the affairs in Europe.