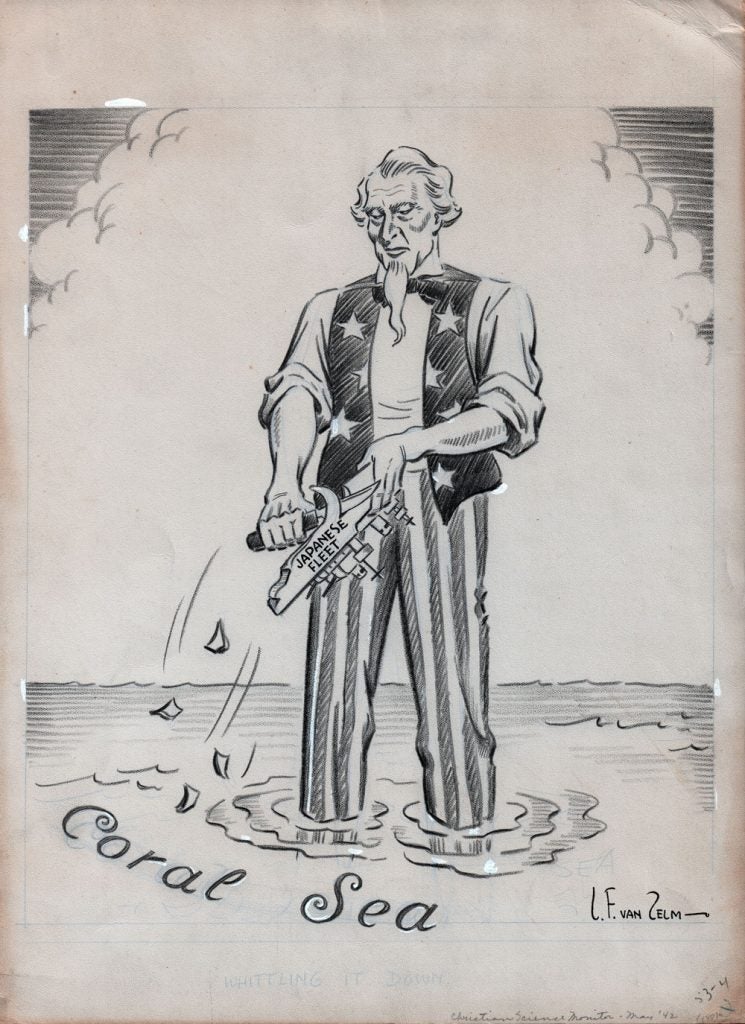

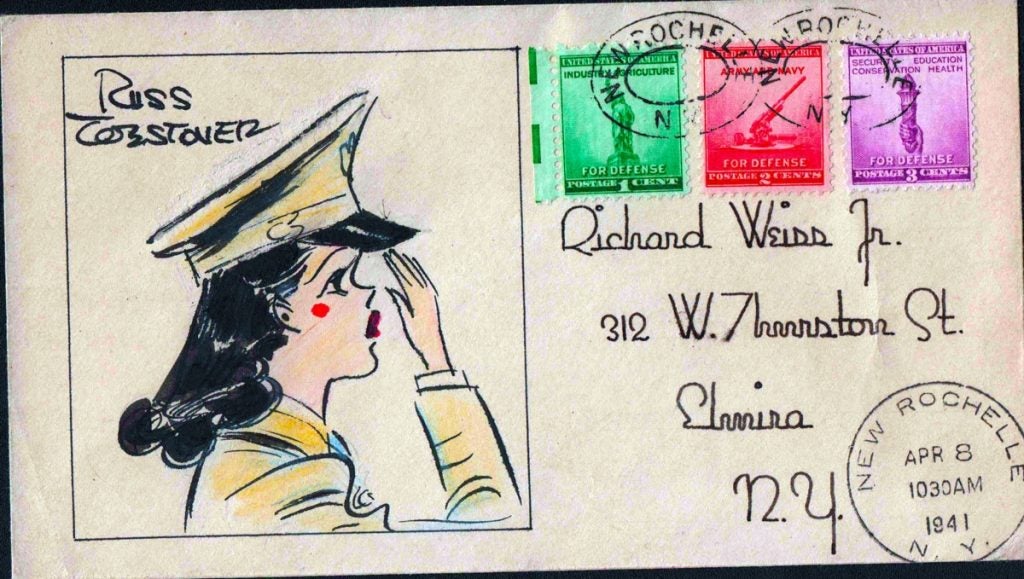

“Tillie” (April 8, 1941)

By Russ Westover (1886-1966)

3.5 x 6.5 in., ink on an envelope

Coppola Collection

Initially a sports artist in California in the 1910s, Westover moved to NY and became a strip artist at the NY Herald. He worked on his concept of a flapper character in a strip he titled “Rose of the Office.” And with a title change to “Tillie the Toiler,” it sold to King Features Syndicate. Leaving the Herald, he began “Tillie the Toiler” for King Features in 1921, and the working-girl strip quickly established a wide readership, leading to a 1927 film adaptation by Hearst’s Cosmopolitan Pictures with Marion Davies as Tillie.

During the late 1920s, more than 600 papers were carrying “Tillie The Toiler.” Cupples & Leon published a series of at least eight “Tillie the Toiler” reprint collections beginning in the 1920s and continuing into the 1930s. Westover profited from another movie when Kay Harris appeared in the title role of Columbia Pictures’ “Tillie the Toiler” (released in August 1941). Westover retired in the early 1950s.

During WWII, Tillie, like other comic strip characters, joined the Army during WWII. This color profile portrait of Tillie, in uniform, pre-dates the US entry into the War, and was done on a postmarked envelope, dated April 8, 1941. The three stamps are all “For Defense” stamps used during WWII. This may be the only known WWII specialty piece by Westover.

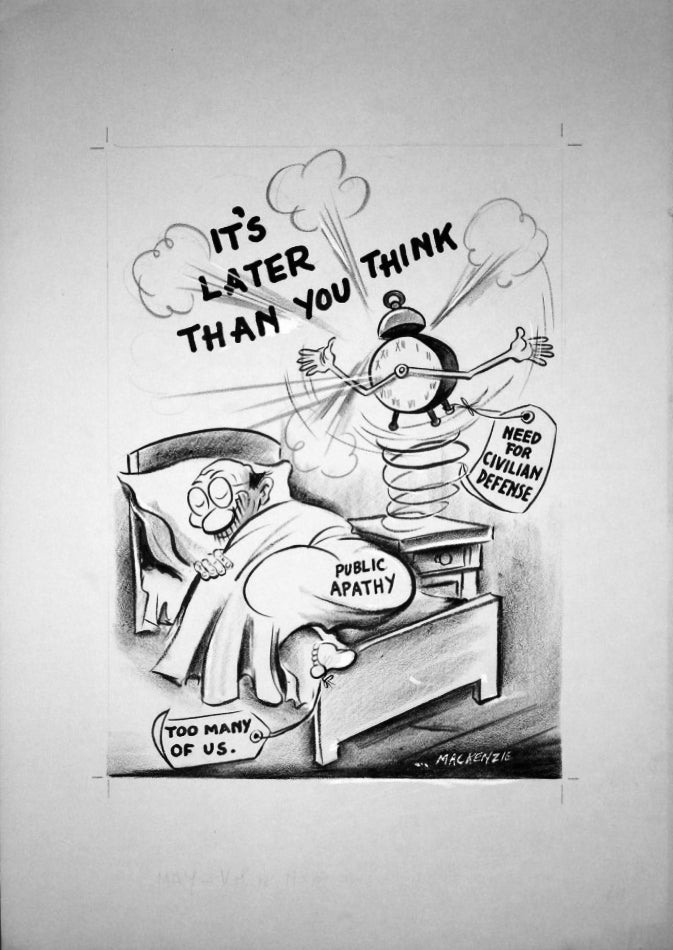

The stamps are not trivial. By the summer of 1940, Americans wanted nothing to do with the European conflicts overseas, holding tightly to their isolationist ideals.

Roosevelt realized it was only a matter of time until Adolf Hitler would narrow his focus on the Western Hemisphere, and felt it was his duty to prepare the nation for when that time came. Roosevelt’s first action to put an end to the American isolationism.

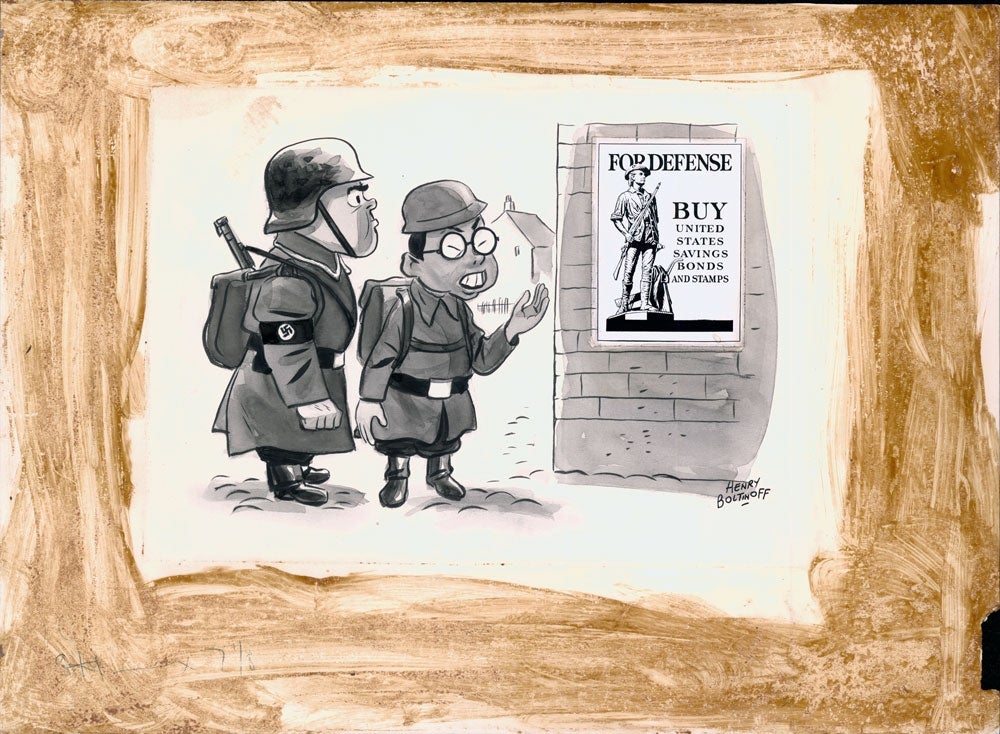

Part of Roosevelt’s plan was to issue postage stamps to educate the public. He provided sketches of what he envisioned to the Post Office Department, and the final designs stayed true to the President’s vision. The stamps were each labeled with their purpose “For Defense” and included inscriptions honoring Industry, Agriculture, Army, Navy, Security, Education, Conservation, and Health as important aspects of the national well-being.

The new stamps were issued on October 16, 1940, which was also the first day of registration for America’s first peacetime draft. When the stamps were issued many more Americans supported the importance of preparedness and the stamps served as a constant reminder of the importance of a strong national defense. These stamps would go on to be the workhorses of the American postal system during the war. Between the three issues, a total of 19,677,985,200 stamps were issued, more than any other US stamp series up to that time.

US #899, the first in the series, pictures the Statue of Liberty that was placed on top of fort built to defend New York against naval attacks. US# 900, the second in the series, pictures a 90-millimeter anti-aircraft gun. US #901, the third and final stamp in the series, pictures a raised torch, representing enlightenment.