My art tastes are difficult to pin down, exactly. I know what I like and I collect it when I can. Of the private collections that I know of, the story and composition of the Barnes Foundation Collection is one that I identify with (although at about one millionth of its scope and without its historical controversy).

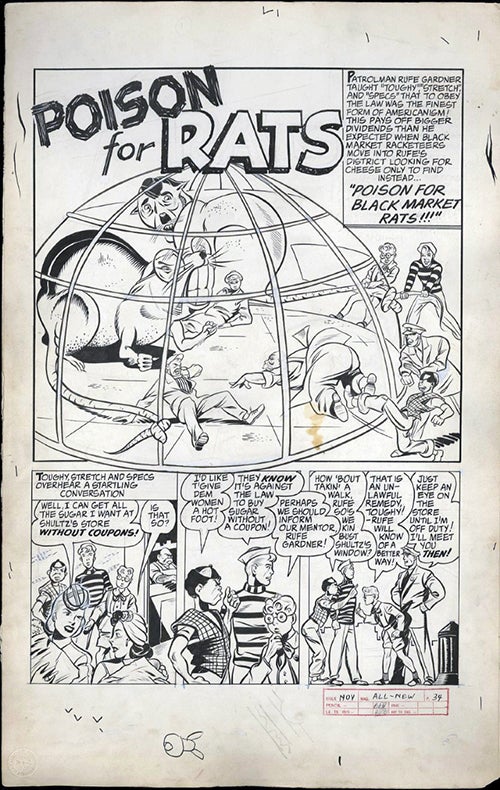

Comic and illustration art makes up the bulk of my collection, and it has exceptionally strong provenance: it is one of a kind, we tend to know where a given copy is located, and it is difficult to forge in the first place. The page contains significantly more information in the original art than is available in the published work, which is poorly reproduced on newsprint, and does not contain the production detail (pencil marks, different inks, and the difference between ink laid down with pen, brush and marker. The original art is often a compilation of work (e.g., the penciller followed by the inker, if not also editorial changes). This information cannot be extracted from the printed version because it is not there, and the information is further obscured by the coloring. The original size cannot be known, exactly, particularly for illustrations. And more to the point, the way in which an artist lays down lines is truly the same as a signature, but the amount of information present is so much more than a signature that getting it all right in a way that jibes with the available printed information is simply impossible. In today’s world of eBay and other internet auctions, or simply individual sellers, anyone even trying to pass off a forgery would face the thousands of eyes of the experts who would weigh in on the validity of a piece.

For the sake of simplicity, there are five broad categories of interest represented in the 高伯乐 Gallery:

I. Comic Book Art (Silver Age to Modern Era): following the boom of the WWII era Golden Age, only a handful of super-hero comics survived into the 1950s. In 1956, the second age of comic book heroes emerged with the introduction of the modern Flash and then, revolutionizing everything, the introduction of the Marvel line of heroes in 1961. As is true for so many, I started reading and collecting these comics in the early 60s. Employed with a salary in the early 80s, one of the first things I did was start to pick up pages of original art. Two representative examples:

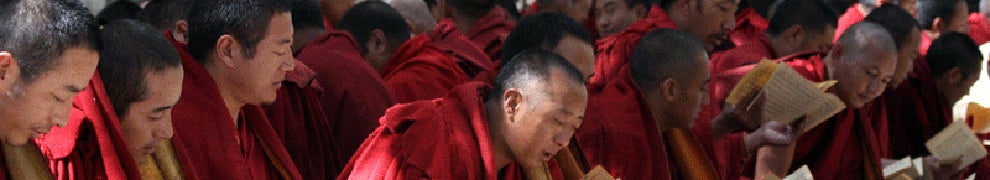

“Fantastic Four Annual #2 page 15” (1963)

Jack Kirby (1917-1994, pencils), Chic Stone (1923-2000, inks)

11 x 15 in., ink on paper

Coppola Collection

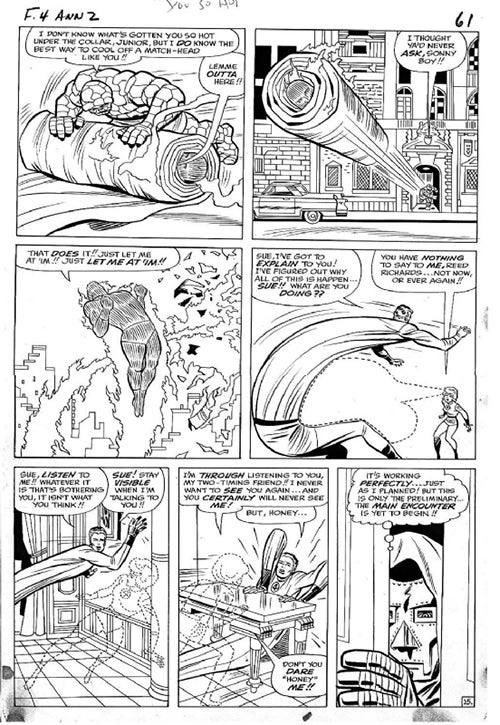

“Hulk #6 page 2” (1963)

Steve Ditko (1927-2018, pencils), Dick Ayres (1924-2014, inks)

11 x 15 in., ink on paper

Coppola Collection

II. Comic Book Art (Golden Age): The modern comic book started in the early 1930s as a way to reprint and distribution the newspaper strips. “Superman” was introduced in 1938. I like the art from WWII era comics because it represents such a boom time for the field, and reflects the world situation as seen through the messages being sent to kids.

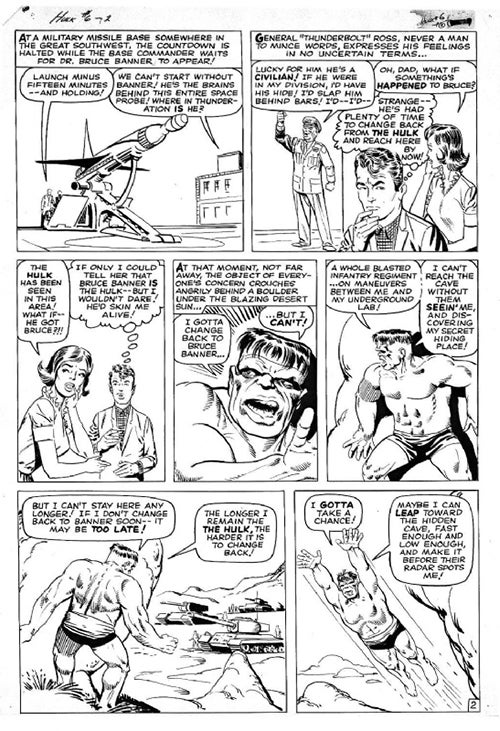

“All-New Comics #11 page 4” (1945)

Art by Peirce Rice (1916 – 2003)

11 x 15 in., ink on paper

Coppola Collection

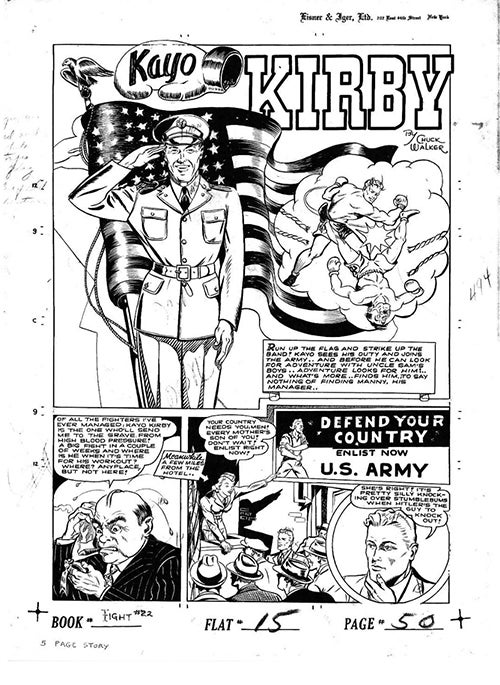

“Fight #22 page 50” (1942)

Al Camy (pencils), Jack Kamen? Al Bryant? (inks)

11 x 15 in., ink on paper

Coppola Collection

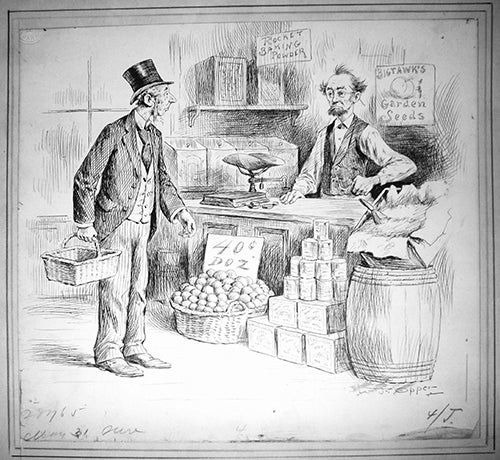

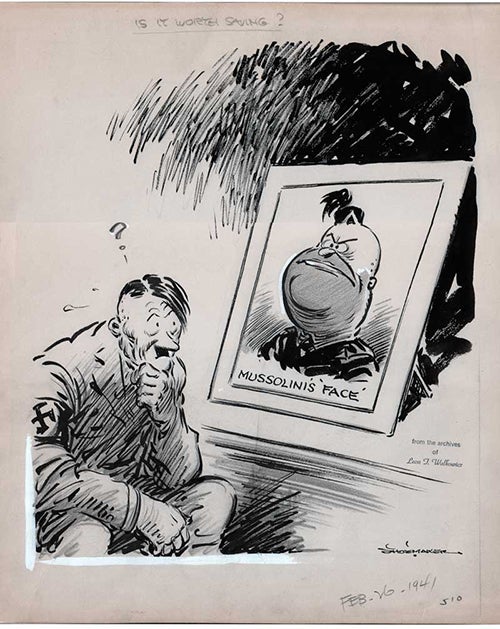

III. Late 19th to mid 20th Century Illustrators: The development of printing technology in the mid-19th C led to the growth of more widespread publications (notably Scribner’s Monthly and St. Nicholas Magazine). The editorial humor magazine, Puck, is credited with moving the genre of political cartooning forward by leaps and bounds, particularly with the advent of color printing techniques. Drawn from the traditional lithography traditions of hash line etchings, these early cartoonists are among my favorites. By WWII, this Golden Era was over, and the growth of photo-reduction was firmly in place. The resolution for this process, however, required some truly super-sized artwork, which makes the hand drawn masterpieces of editorial work that much more spectacular. The rapid, day to day commentary that one finds in the WWII editorial cartoons, with daily editions of newspapers all over the country, creates a kind of “social media” view of current events that would persist, in this form, until the immediacy that television brought to the Vietnam war in the 1960s.

Illustration from Puck(?) ca. 1880-85

by Frederick Opper (1857-1937)

18 x 18 in., ink on paper

Coppola Collection

“Is it Worth Saving?” (February 26, 1941)

by Vaughn Richard Shoemaker (1902-1991)

24 x 36 in, ink on paper

Coppola Collection

IV. Contemporary Fine Art: I cannot present “representative” anything here, so I will not. There are a handful of young artists who work in oil whose work I collect, and whom I like to support. Abbey Ryan was the first among these, and I love her paintings because of the 17th C “Dutch Masters” sensibility she brings to the canvas. So I include one of my favorite Ryan paintings here. The other one I decided to include is by Jeffrey Catherine Jones, an artists whose work spanned innovation comic book, science fiction and fantasy painting and illustration to a body of work in oils. While I have some of the former, it is actually the latter that I prefer, and the one included here (Red Sky) is one of my most treasured paintings.

“Still life with Jug, Cantaloupe, and Figs (the light, the shade)” (2014)

by Abbey Ryan (1979-)

11× 14 in., oil on linen on panel

Coppola Collection

“Red Sky” (2006) or “Red Palm” (2006)

by Jeffrey Catherine Jones (1944-2011)

18 x 24 in, oil on canvas

Coppola Collection

V. Sculpture, Jewelry, and Ancient Artifacts: Showing representational pieces just went from difficult to impossible.

“Patient Dignity” (2016)

by Tobbe Malm (1960-)

12 x 13 in, iron

Coppola Collection

Kraak Plate Pair (ca. 1625; Wanli wreck)

cf: Sten Sjostrand, Nanhai Marine Archeology

24 cm diameter, porcelain

Coppola Collection

“Dot Ring” (2015)

by Daniel Macchiarini (1954-)

gold, ebony, copper, ivory

Coppola Collection