In the year 1625, a Portuguese vessel set off from China on a voyage to the Straits of Melaka. Onboard were tons of chinaware and pottery that would bring lucrative profits for the Portuguese.

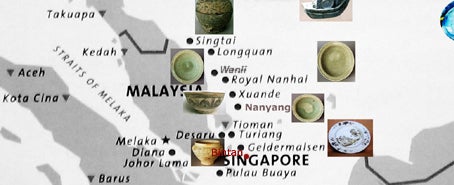

However, the ship now named “Wanli” never reached the Portuguese fort of Melaka as she sank half way sailing through the South China Sea. The wreckage was discovered buried deep in the ocean off the coast of Terengganu, together with her precious cargo, six miles off the east coast of Malaysia after pottery appeared in fishermen’s nets in 1998.

The ship was found six years later, loaded with blue and white antique Chinese porcelains belonging to the Ming Dynasty, the ruling dynasty of China from 1368 to 1644. The vessel became known as the Wanlishipwreck after the recovered ceramic was assigned to Guangyinge site in the town of Jingdezhen during the reign of Emperor Wanli (1573-1620).

See below for a bit more about Jingdezhen and the history of blue and white porcelain.

Jingdezhen (China)

A great deal of pottery history centers around Jingdezhen, a city located in the northeastern part of Jiangxi province (NE China), which is known as the porcelain center of the world. Ceramics production is thought to have started there about 2000 years ago with kilns spread along the Chang River.

Pottery clay was in ample supply all around the town. Gaoling mountain, 40 kilometers to the northeast, is one of the few areas in China that provided pure kaolin, an aluminum silicate that is an essential ingredient for porcelain. Nearby areas provided another key ingredient, the so-called ‘China stone,’ a non-iron-bearing igneous rock.

Pinewood was found in abundance around the town and was used to fuel the kilns, while the Chang River provided transport for raw material to the kilns as well as for later shipping of the finished products.

Blue and White Porcelain

During the Song dynasty (960-1279) high-fired ceramics were immensely popular and developed to perfection. Although large quantities of Chinese pottery were exported to Southeast Asia, India and the Middle East from the 9th century, it was the Yuan dynasty (1280-1368) under the rule of Kublai Khan that significantly expanded maritime trade. Artisans escaping the Mongol invasion of northern China appear to have migrated south and assisted in the technical and decorative achievements of porcelain making in Jingdezhen. The technique of painting with iron black oxides before glazing, so long practiced elsewhere in China, may have given birth to the first cobalt decorated wares of Jingdezhen. This technology transfer resulted in the best-known ceramics of all time – blue and white porcelain.

The seaports established by the Song court became even more successful under Mongol rule. Marco Polo (1275-1292) wrote that Quanzhou harbor was the greatest port in the world and also mentioned the ceramics trade.

While production for overseas markets was reduced, private kilns in Jingdezhen made blue and white porcelain for the huge domestic market. Work for the official kilns was increased in 1433 when the Ming court ordered 443,500 pieces of porcelain for the imperial household.

Internal and External Markets

Individual owners separated the fired wares into different quality groups and priced the export ware accordingly. First class wares had the brightest color and no kiln defects such as warping; pieces with lower density color became second-class. The remainder was sold on the domestic market. Ceramics intended for overseas markets were packed in straw bundles and sent to the river for onward transport. The domestic ware was not packed in straw but tied up in bundles of 30-40 pieces before being distributed.

Continued developments at Jingdezhen during the early Qing dynasty resulted in the finest porcelains ever made – those from the Kangxi (1662-1722) reign.

Merchant Trade with Portugal

In Europe, the Portuguese made technical advances that led to the development of a merchant fleet. And their goal was to purchase spices directly from Southeast Asia rather than via Muslim middlemen in the Middle East and other agents in Italy. As a result of this desire for spices, they found Chinese porcelain first in India and then, after their settlement in Melaka was established in 1511, in China. The first pieces of Jingdezhen ware brought back to Portugal by ship were acquired in India and presented to King Manuel I by Vasco da Gama.

The taste for Chinese porcelain in Portugal and elsewhere in Europe slowly gained popularity during the later part of the 16th century when the Portuguese royalty gifted other European nobilities with this exclusive commodity which they alone could acquire at source. Here it is important to note that Chinese celadon, an important export in earlier times, rarely entered the trade with Europeans. Blue and white porcelain had already become more fashionable than celadon in the 15th century, and the Portuguese arrived at the beginning of the 16th century.

The quality of the Jingdezhen porcelain falls into two distinct basic groups. One was made strictly for the imperial court and the other for the domestic and export markets. Because imperial ware was made to strict specifications, personal artistic expression by the decorators was not only minimized but simply not allowed. As a consequence of strict quality control, imperial porcelain may tend to appear artistically lifeless but is famous for its technical qualities.

Igniting the Craze

It is difficult to ascertain the volume of Jingdezhen porcelain intended for the European market in the later part of the 16th century due to lack of records. However, in the early 17th century, when the Portuguese carrack Santa Catarina was captured by the Dutch, there were more than 100.000 pieces of porcelain in her holds. When later auctioned in Holland it started a Dutch craze for Chinese porcelain. Its fame spread to the rest of Europe by the second half of the century.

Export production at Jingdezhen witnessed yet another boost when the Dutch arrived in China in the early 17th century. With the Portuguese well established in Macao, the doorstep to China, the Dutch had repeated disputes with the Portuguese and the Chinese administration. Misbehaving, as the Portuguese did before them, the Dutch were forced to trade along the Chinese coast and from various illegal settlements with primarily Fujian merchants.

Following the sale of the porcelain cargo from Santa Catarina, it has been estimated that between at 1604 and 1657, more than three million porcelain pieces were shipped to Europe by the Dutch alone. Adding the even higher volume of porcelain for Southeast Asian markets, the total production at Jingdezhen was staggering.

The Wanli Period

In the late Wanli period (1573-1620) imperial orders for Jingdezhen had dwindled. At the same time some of the official kilns were razed during peasant revolts and eventually closed in 1608. During this ‘transitional’ period (circa 1620-1663), some private kilns managed to stay in production for an ever increasing export market.

From about 1634 onwards, Chinese junk captains took orders from the Dutch for porcelain in special shapes for which models of European objects were provided. There were also special patterns including ‘Dutch flower-and-leaf work’. Some designs were initially incorporated into typical kraak panels, a practice that shows how the Jingdezhen decorators adopted new motifs to please their buyers.

Until late 1630s the supply of porcelain from Jingdezhen was relatively steady, but in the early 1640s there were reports of war in Jingdezhen and high mortality rates among the potters. Production continued, and in large quantities, but supply-lines remained uncertain. About 1657, the Dutch started ordering much of their porcelain from Japan.

Shipping and its hazards

With hundreds of thousands of pieces of porcelain transported during most years of the 17th century and into the 18th century, the transport of porcelain was another large industry in itself. With large numbers of small boats navigating sometimes small and winding rivers, coming and going, the rivers were both crowded and dangerous, not least for the fragile cargo.

The relative ease of transportation on the Chang River and its tributaries was a key circumstance in the successful development of the porcelain industry in Jingdezhen.