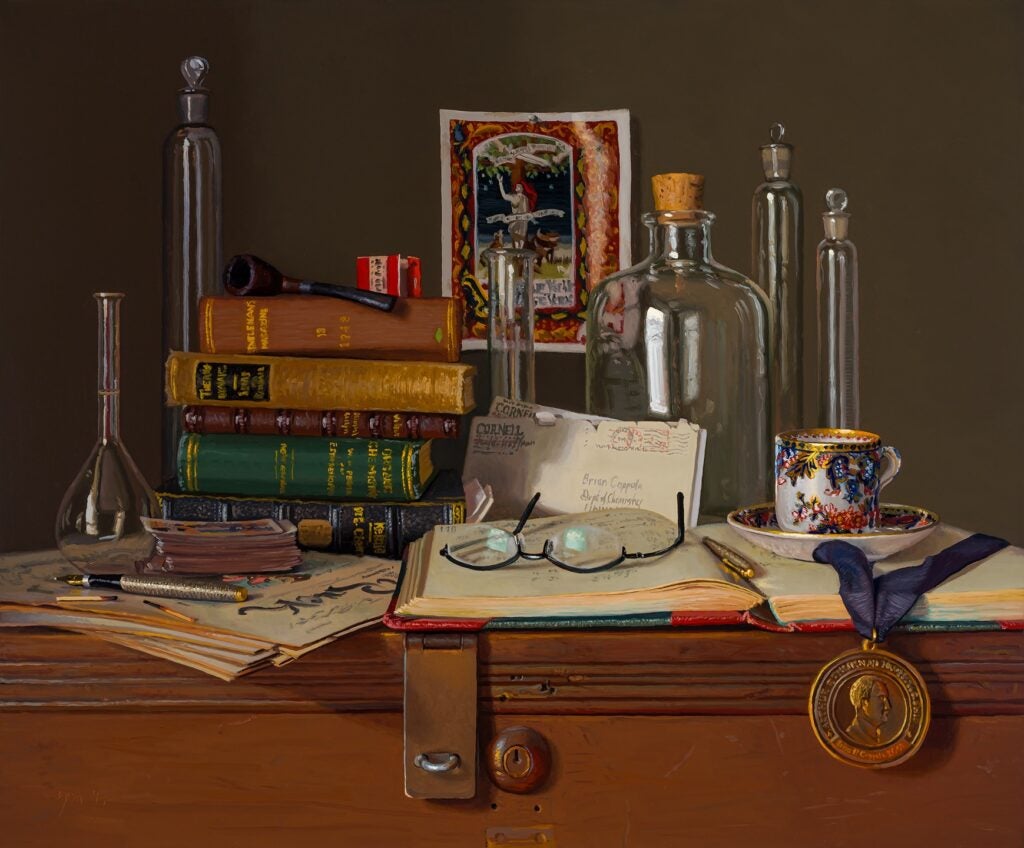

“Natura morta con formaggio, frutta, noci e vino”

20×24, oil on canvas

Abbey Ryan, 2023

In 2017, when I turned 60, I commissioned a pair of “legacy” paintings from Abbey Ryan, whose work I have collected for many years. The concepts were to pay homage to my career as a chemistry professor (the companion painting) and also to my Italian heritage on my father’s side of the family (this painting). Abbey is an excellent painter whose style evokes the Dutch Masters, and whose work could easily be mistaken for paintings from straight out of that era. These are the largest and most complex compositions she has attempted to date (and knocked them straight out of the park). Nearly all of the objects came from me, and she gets 100% credit for everything else.

This painting is titled “Natura morta con formaggio, frutta, noci e vino.” What you see is what you get: Still life with cheese, fruit, nuts, and wine.

Abbey evokes the style of the Golden Age of Flemish art. She has specialized in simple still life compositions, famously for depicting cross-section slices of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches.

In the 17th century, the advent of the Still Life as a subject emerged with the Flemish painters. The Still Life painting was a great opportunity to display skill in painting textures and surfaces in great detail and with realistic light effects. Food of all kinds laid out on a table, silver cutlery, intricate patterns, and subtle folds in tablecloths and so on. Dutch painters produced still life paintings in great numbers, reveling in the Dutch “love of domestic culture.” The English term Still Life derives from the Dutch word stilleven (stil + leven), which came into use about 1650. Over time, several types were recognized: banketje were “banquet pieces,” ontbijtjes simpler “breakfast pieces.” Virtually all still life paintings had a moralistic message, usually concerning the brevity of life (more about this later) – this is known as the vanitas theme – implicit even in the absence of an obvious symbol, or less obvious one such as a half-peeled lemon (like life, sweet in appearance but bitter to taste).

Abbey’s work most reminds me of Floris Claesz van Dijck, who is credited with originating the banketje subject, of which my painting is obviously representative. The major holidays during my youth were filled with tables of food laid out by my paternal grandmother, in a small house crowded with friends and relatives. No one goes home hungry.

The black and white picture on the wall is the earliest recorded image, from 1903, of my father’s family having immigrated to the United States from Sicily. They settled in a community north of Boston up near the New Hampshire border. The family made shoes in Italy but learned how to make Sicilian cigars before coming over, anticipating the interest in having that taste of home within the immigrant community. They set up connections for importing the Sicilian tobacco and opened up the “Coppola Brothers” cigar store at the location shown in the picture the year before my grandfather was born. His father got into trouble more than once for tax evasion over the tobacco imports, and the store, which was located next door to a bakery, was reputedly a location for making fermented beverages during Prohibition. The store was in operation at that location for decades. The picture, and the cigar in the painting, honors this family business, and the matches are the same as in the other painting and come from Abbey’s collection.

For the most part, many of the Italian immigrant families’ strong cultural roots were snipped in the 1940s, when Mussolini made the US an enemy and many Italians disidentified with their country of origin. My dad and his siblings were not permitted to learn to speak Italian, and there are stories of families walking through their houses smashing anything made in Italy. That said, the family was unsurprisingly Roman Catholic. Weddings were huge, lengthy, solemn, and filled with Latin. By the time I was born, both of my parents had long since abandoned their respective churches, and I have exactly zero belief in supernatural beings or phenomena. I respect the role religion has played in human culture, however, and wanted to honor that part of the heritage. I found a nicely crafted diorama of the crucifixion and sent it to Abbey for the painting. It now hangs as an art piece in my guest room. I have a few cool art pieces of religious subjects in the house, in fact.

The dark glass vases are mine. My parents and my favorite aunt both collected this black amethyst glass. These are Depression Era art glass pieces. The glass shows intense purple but only when you hold them up to a bright light source.

The medallion is an 1875 bronze medal that was awarded in a European archery and crossbow competition. It’s an oblique reference to the family being from Europe through the late 1800s (the Coppola family history in Sicily has been traced back to the early 1600s).

The white glass fruit bowl was my grandmother’s. It was always on her kitchen table, and I used to play with its textured surface as a kid. I am happy to have ended up with it and to use it as a focal point. I bought the old Italian linen embroidery for the painting. A bottle of Coppola wine was a no-brainer (no relation). That Coppola merlot is one of the few wines I ever enjoyed, actually. I am a hyper-taster for both acid and base, and never got past the sharp taste of wines until a friend recommended the Coppola merlot. It turns out to be one of the lowest acid content wines on the market.

Back to the historical symbolism in Still Life paintings. The vanitas theme in artwork illustrates the transience of life, the futility of pleasure, and the certainty of death, often featuring heavy-handed allegory in the form of skulls, insects, rotting plants, candles burning low and hourglasses draining out the last few grains of sand. Vanitas take its name from the King James Bible: Vanitas vanitatum omnia vanitas, “Vanity of vanities, all is vanity.”

Abbey knows all this, and she honored her own work in creating this first-ever complex banketje painting with the inclusion of a musca depicta. This is a fly, slightly larger than the life proportion of painting, included somewhere in between being a surprising part of the composition and as a trompe l’oeil object that you want to brush away from the surface. You do not expect to see it and you likely missed it when you looked at the painting. But it is there in plain sight. Many delicate religious paintings, including Madonna and Child subjects, include a musca depicta or two.

Shoo fly.