We’re delighted to see that CSSH readers have spent the last month sampling Matthew Shutzer’s essay, “Subterranean Properties: India’s Political Ecology of Coal, 1870-1975,” winner of the 2022 Goody Award. There are many things to admire about the piece. For those who have not yet read it, the Goody Award panelists (Amy Chazkel, David Mosse, and Philip Gorski) provide an insightful assessment. We thank them for the careful attention they gave a shortlist that included three other essays, each an example of the journal’s most innovative work:

Danna Agmon, “Historical Gaps and Non-Existent Sources: The Case of the Chaudrie Court in French India“

Charles Anderson, “When Palestinians Became Human Shields: Counterinsurgency, Racialization, and the Great Revolt (1936-1939)”

Gervase Phillips and Laura Sandy, “Slavery and the ‘American Way of War,’ 1607-1861“

In keeping with CSSH tradition, we’ve invited Shutzer to answer a few questions about his essay. Since he is the fifth winner of the Goody, we were eager to know what he makes of a curious trend.

What trend, you ask?

Read on.

CSSH: First of all, congratulations on your win!

Shutzer: Thank you! It was a wonderful surprise, and an honor to have the article considered. I think you’re supposed to cultivate a dispassionate attitude about these things, but I was genuinely overjoyed.

CSSH: Your paper focuses on law. Goody winners are almost always writing about legal problems or legal frameworks. Do you think that’s a coincidence?

Shutzer: Well, it may be a trick. The law is attractive because it’s both conceptual and normative, and legal archives are centrally about the languages and institutions of social power. In the best of cases, work on the law is reflexively about our own methods of interpretation – how concepts come into being and how concepts do work in the world. Even if you’re not invested in the law per se, you can probably appreciate it as a meaningful site of struggle, and as a place where individuated phenomena become assimilated into abstract justifications and principles. The law can jump scale in ways that other languages cannot. Maybe people like the law because it’s a way of staging broad conversations about method that appear to be about something else.

CSSH: That sounds right. Your own essay is multilayered in this way. It moves gracefully between British statutory law, Indian customary law, improvised contract law, revamped Mughal law, and colonial legal innovations that appealed to precolonial precedent. It’s about power and struggle. And rationalizations of diverse kinds. All of that is impressive enough, but the analysis is best when (so to speak) you drive it into the dirt, showing us how agrarian legal traditions oriented toward the productive surface of the soil were reformulated to address property rights and resources that lay underground. This “verticality” allows you to historicize the exploitation of Indian coal above and below ground, three-dimensionally, and over a century. It’s a strange effect, one a study of law, or mining, or the agrarian political economy couldn’t produce on its own.

Shutzer: In a way, the procedure for writing the piece was the reverse of what you describe. It began actually in the “dirt,” using on-the-ground archives to tell a story about the transformations of land and property. The law came later, only after I was able to get comfortable with what it meant to write about the production of a certain type of legal silence. You know, everyone always pays homage to the importance of what the archive structurally excludes, but in practice making sense of a “silence” that the archive itself produces and comments upon was pretty challenging. I initially read colonial officials saying “there’s no way to determine who owns subterranean property” and naively thought “oh okay, this is just some weird situation, there’s no way to make sense of what’s not there.” But when I left the world of property records and company documents and began to read the legal archive, I realized that those silences had an active presence in shaping what was happening on the ground. That’s when I understood that the pieces only made sense by showing that these legal silences were anything but, which meant bringing agrarian political economy into conversation with the law.

CSSH: That’s what makes your argument so refreshing. You don’t overdraw the distinction between political economy and law, or between custom and law. Instead, you show how agriculture and coal mining were connected and competing systems. The legal history develops as an aspect of those relationships.

Shutzer: Right, well, it’s the political ecology framework that helps with that. Property law creates social and institutional conditions for drawing surplus out of the land, but you have to begin by taking seriously land-based social practices that precede and overflow this practice of formal codification. If there’s anything that South Asian agrarian history has taught us, it’s that we should be distrustful of accounts that posit the totalizing impact of law, and especially to resist the temptation to use legal archives as the basis for making claims about the inseparability of law and capital. All sorts of things attenuate the reach of law, which anyway enters into pre-existing fields of social and political power, as well as specific ecologies and landscapes, that ultimately shape what the law is called upon to do.

Agrarian histories of South Asia have been especially successful in blending law and political economy through accounts of custom. The whole project of custom is central to colonial ideologies of governance, and so it’s not surprising that studies of property regimes often turn on what does or doesn’t count as “customary,” or how custom itself becomes a way of talking about both property and social order. What was interesting to me about nineteenth century debates on mineral property, however, was that colonial officials seemed to be asking a different type of question: what happens to a system of property rights ordered by custom when we can’t really establish what would define minerals as a form of property? The fact that the question could even be formulated in this way is itself kind of interesting, because of course the entire colonial edifice for recognizing customary property was based on fungible criteria that could have easily accommodated claims to subterranean rights, and in some cases did. So why colonial officials talked about the subterranean in terms of a legal absence, or a gap in custom, struck me as a strange problem, related to some type of internal inconsistency in the objectives of colonial law-making.

CSSH: Yes. It’s even more puzzling in relation to your account of the early days of coal extraction in the frontier zones, when mining companies made use of customary law to get at the coal and to organize the labor and political protections they needed to run their operations. Suddenly, or so it seems, this reserve of customary law was deemed inadequate, or impractical. What was missing?

Shutzer: There were good reasons to think in terms of legal absences. I’d find out later that much of this had to do with the problem of minerals within conceptions of imperial sovereignty. What moving into the subterranean as a site of law-making allowed me to do was to shift from agrarian histories of customary property to debates about statutory power. This was a world I was totally unfamiliar with. I quickly learned how important statutory debates around the law of real property were to legal disputes in the British Empire. So much of what got to count as custom turned on definitions of property and nature that were determined not by the identification of pre-existing right, but by the importation and development of statutory law. What statute enabled was a way of reconfiguring agrarian landscapes in ways that were amenable to competing claims to property and nature …

CSSH: Claims to a field, or a crop, as well as rights to a seam of coal located beneath both.

Shutzer: … without doing away with the residual legitimating discourse of custom. Suddenly things like land could be understood in terms of their component parts, or as three-dimensional property-adhering spaces. This is where the category of “minerals,” for instance, as a legal substance, comes from. There’s a whole other conversation we could have about whether or not it’s correct to understand custom and statute as grounded in separate notions of legal authority.

CSSH: We’d love to have that conversation! It’s been central to so much good CSSH scholarship. One of our early IN DIALOGUE features dealt with varying conceptions of legal authority. Could you give us a quick sense of what interests you about this question?

Shutzer: What I found illuminating was the invocation of custom and statute in property disputes as if they were separate, as well as what seemed to be the largely arbitrary basis on which judges came to claim one type of legal definition over another. Being able to invoke competing and often contradictory statutory claims about what physical substances constituted land or minerals under the law was a profound source of power, with lasting consequences for the regime of property that grew up in India’s coalfields.

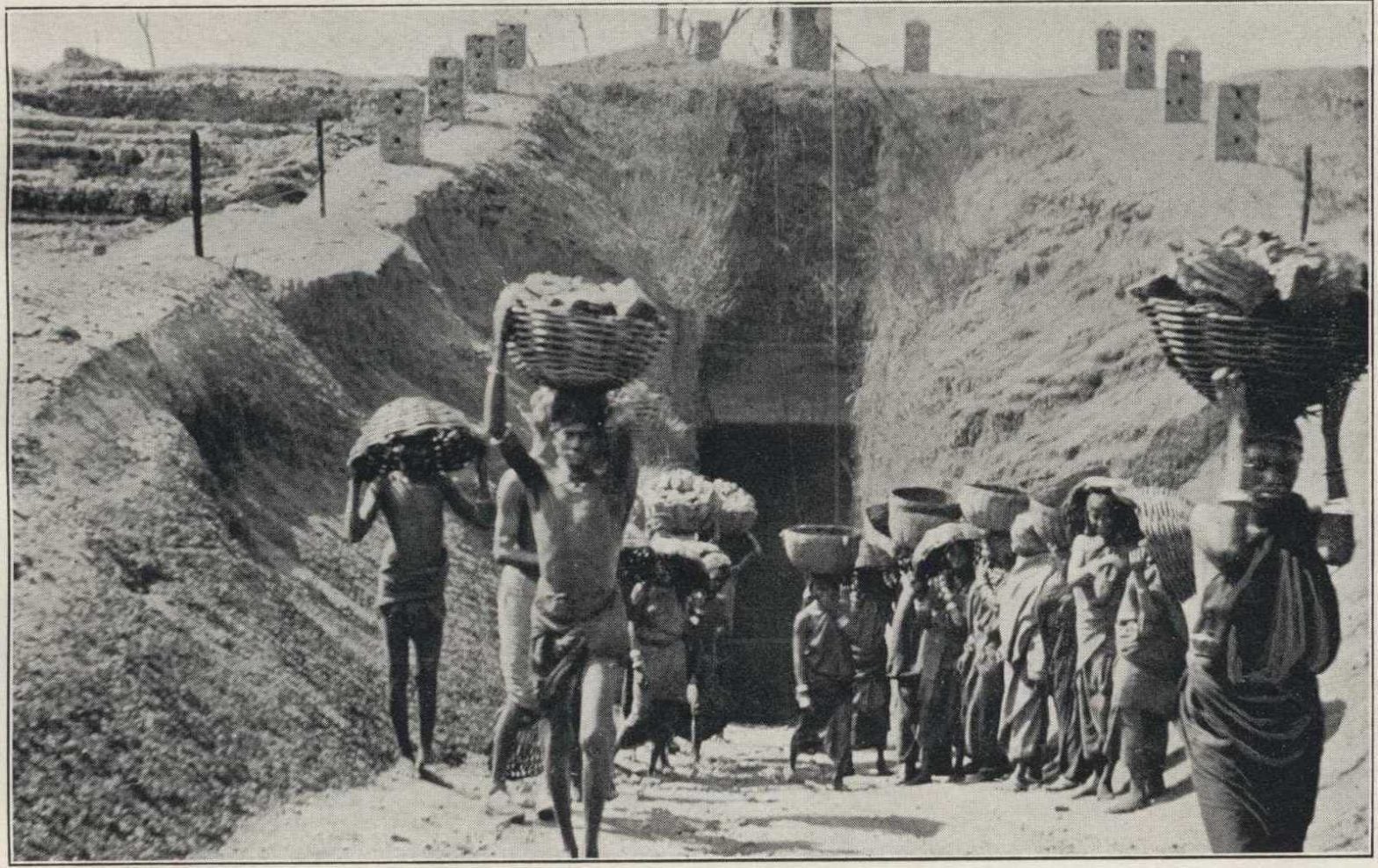

CSSH: The fact that coal was literally underneath an “agrarian political economy” is another remarkable contingency. Whatever else they were doing, the coal companies were “harvesting” coal. They didn’t plant it, but they did have to dig it out, as if it were a root crop, and they used agricultural laborers to do it. Part of the tragedy you so vividly describe is, in redeploying agrarian labor, the mining companies took something that was renewable, or repetitive — sustainable is a “now” word; best to avoid it — and turned it into something destructive and, as you put it several times, “opportunistic.” Disastrous, too.

Shutzer: One of the most exciting areas of research in my field has been the turn, since the late 2000s, towards an understanding of how colonial and post-colonial state regimes have mobilized colonial-era laws to enable land dispossession for private capital. My work is part of this conversation, but I also wanted to highlight some of the limits of its logic. If we presuppose that capital requires the state to work in this way, one of our presuppositions might be that capitalist firms prefer to work within formal frameworks of legality. Or, to use the jargon of a different field, firms prefer to allow states to absorb transaction costs. This might be a useful way of thinking about the present, for instance, but it’s not at all clear to me that such an account is useful for making a general statement about law and capital historically. There’s a kind of functionalism here, about capital remaking the law in its own image iteratively. For writing colonial legal history, such a tendency also appears, but with different stakes. The colonial state makes laws to benefit metropolitan capital, or to rationalize society and nature in ways that benefit specific forms of quantifiability. These laws produce a fundamental separation between colonizers and the colonized, shaping what we think of as the “cultural” world of what gets called vernacular capitalism and the “economic” world of European-dominated trade.

CSSH: This kind of bifurcation was not present at the beginning of the legal evolution you describe. At first, there was a complex, overlapping, deeply-grounded-yet-negotiable “mess” of customary relations and obligations the coal companies used to secure their claims. The amount of local knowledge needed to pull off these agreements would have been considerable, and not exactly easy to come by. It required familiarity with existing agricultural systems, but also with the rules used to manage the flow of commodities and people in the frontier regions before coal, before the British even. This body of precedent was built into hierarchical systems, into caste formations that extended into the forests, where Indigenous communities practiced shifting agriculture. It’s an amazing landscape, even in your brief, essay-length description of it. It’s not a landscape in which clear distinctions between the cultural and the economic were possible.

Shutzer: As I said before, I’m interested in how such binaries are trespassed. The use of custom to acquire coal land was at first a result of a shared, rather than bifurcated, social world of agrarian landholding linking European investors with Indian landowners. Later, it became a deliberate strategy for generating surplus by controlling labor and land. My ideas were shaped by reading scholars like Nancy Fraser, Silvia Federici, and Jason Moore, who in different ways have been trying to understand the institutional arrangements by which capital doesn’t pay its full costs of doing business. Coal companies resisted the application of more secure property rights in mining areas because custom allowed them to manipulate “traditional” hierarchies of land and labor control. Law in this way was a hindrance to accumulation; while the “fuzziness” of Indian custom could serve much more profitable ends.

CSSH: The labor issues involved are fascinating. The coal companies, to get at the coal, had not only to purchase rights to it — really, “access” to it — but they had to shoehorn a substantial portion of the above-ground agricultural political economy into the process of extracting the coal. They had to organize a workforce that was a repurposed version of above-ground labor, including its management (or coercion). There was already an immense amount of “precedent” in the above-ground political economy, expressible as custom or law, as binding or bound relations. Your paper is remarkable in its portrayal of how mining companies worked with and against these precedents, how they exploited the small windows of time in which above-ground economies could be shuttled underground to extract coal.

Shutzer: This type of opportunism was also a feat of archival power. The largest companies and landowners in the region controlled the records of customary property going back to the eighteenth century, which enabled them to manipulate, lose, and promote property deeds of their choosing. This shaped the reality of custom on the ground, while also connecting European firms with what was pejoratively called the “feudalistic” practices of Indian estate-holding. I was lucky that one of the largest of these companies kept an archive dedicated to their land acquisition strategies, which offered a window onto exactly how they thought about these things. They were cognizant that the categories of agrarian landholding they used to mine the earth were anachronistic, but that was precisely the point.

CSSH: You tell us at several points that your analysis has comparative significance. The Goody judges agree. You don’t oversell this claim, but we’d like you to say more about it. How can a study like yours, which emphasizes contingency, local precedent, and a very particular colonial history, be put to good comparative use?

Shutzer: You already mentioned the article’s structure of “verticality.” That was what I was hoping to achieve, so I’m glad it came off. It was intended to do both comparative and conjunctural work. What I wanted to do was to show how, over a period around 10-12 years, the unprecedented intensification of Indian coal production transformed the regime of property used to govern subterranean space. Well, it actually invented subterranean space, which was then naturalized recursively as it if had always been that way.

To understand how that process of transformation and naturalization happened, you need to understand the very specific histories of property and land use that preceded it, because all of that stuff goes through the 10-12 year commodity boom and comes out the other side looking very different. I thought a lot about the metaphor of “sedimentation,” which comes from Lefebvre’s piece on “Rural Sociology,” where he talks about how sociologists looking at contemporary relations of rent quickly come to realize that the ordered phenomena they are observing in the present contain within themselves all of these messy, contradictory remains from the past.

The point for me was to show, okay, this thing we’re calling the subterranean has all of these real effects in the world, but it disguises all of these other socio-ecological relations that overflow the neat ordering of space. Some of these relations are vestiges of the past, others are actually sedimentations, anchored in the interplay of geology and long-term cultivation. This is the outline of a critique of property that I really care about. It’s one thing to unmask property as ideological or socially constructed. I think it’s another thing to show how a property relation is created by people on the ground struggling over the surplus of land and nature.

CSSH: What’s next for this project? We assume it’s evolving into a book. Is anything unforeseen happening (to you or the data) as that process unfolds?

Shutzer: An extended reflection on these themes is coming out as a co-authored article with an environmental lawyer, Arpitha Kodiveri, sometime next year. If the piece in CSSH was an exploration of property, this subsequent work is more centrally concerned with sovereignty and, basically, how sovereignty inflects current thinking on fossil fuels and climate change.

The book is on its way. What’s been a bit unexpected in writing the broader chapter that draws themes from “Subterranean Properties,” is that in the last year or so it really became an exploration about the category of “feudalism.” What I’m trying to do is to rethink older debates about capitalism in colonial India through the problem of feudal property as it pertains to energy extraction. I know it sounds maybe off beat. But actually there’s a lot that’s not dead about feudalism, or debates about it, for thinking the history of extractive economies.

CSSH: That’s another area in which your paper lays solid groundwork for comparative analysis. We agree with you. Feudalism is still with us, and it often flourishes in the places and institutions most invested in its archaism. We need new ways of thinking about this. When you figure it all out, send us the manuscript!

Matthew Shutzer is an interdisciplinary scholar of modern South Asia specializing in environmental history, the history of capitalism, science and technology studies, and the history of global decolonization and development. His forthcoming book is a study of India’s fossil fuel economy from the nineteenth century to the late-twentieth century. His writings have appeared and are forthcoming in The Radical History Review, Past and Present, History Compass, Borderlines, Warscapes, SAMAJ, and in the edited volume Staking Claims: the Politics of Social Movements in Contemporary Rural India. He is currently an Academy Scholar at the Harvard Academy for International and Area Studies, and was previously appointed as the Ciriacy-Wantrup Fellow in Natural Resource Economics and Political Economy at the University of California, Berkeley. In 2023 he will begin as an Assistant Professor in Global and International Studies at Bard College.